Entertainment

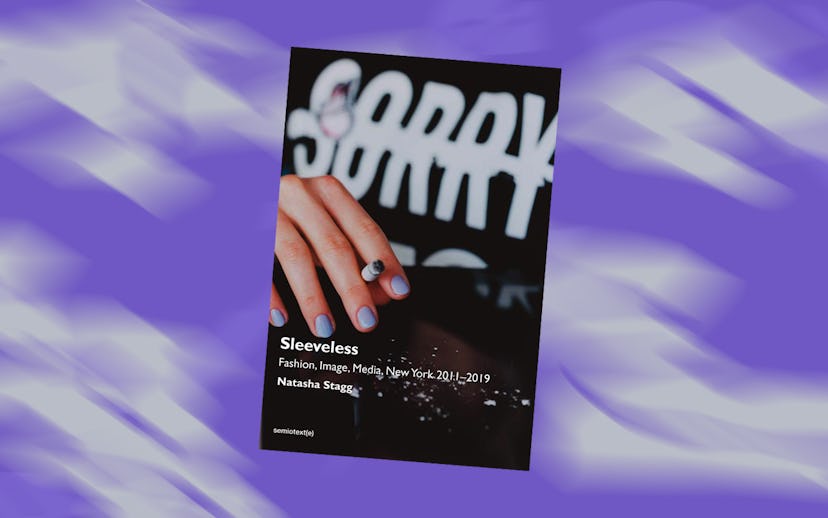

Natasha Stagg Thinks It's A Great Time To Be Living In New York

Talking with the author of 'Sleeveless' about her book, fashion, celebrity, and life in New York

"I think I moved to New York with an idea of what type of writer I would be," Natasha Stagg told me over the phone, recently, during our conversation about her new book, Sleeveless: Fashion, Image, Media, New York 2011-2019. Stagg is not, of course, the first young writer to move to New York with a fantasy of fulfilling a certain kind of literary dream, nor is she the first to make that fantasy into a reality; Stagg has been an editor for V Magazine, where she profiled celebrities, and has elsewhere written extensively and with diamond-sharp clarity about such ill-defined and -understood topics as fame, fashion, and culture.

But, when Stagg talks about her journey to New York and the professional dreams that brought her there, there's nothing about her experience that makes it seem like it's been done before. Rather, Stagg's path has resolutely been her own, and it's only possible to think of her as ever having been starry-eyed in the sense that her authorial gaze is searingly hot, always lucid even when tackling the murkiest of subjects. And yet, this doesn't mean that Stagg ever loses her cool; she is someone who writes so well about the party that is life in New York in part because she's always at the parties—at least, all the ones that matter.

Sleeveless is a document of the party that has been the last decade in New York. A mixture of essay and fiction (there is no clear delineation as to which is which, but there doesn't need to be to understand what is real and not), Sleeveless is a snapshot of our current decadence, a record of the rapidly changing industries (fashion, media, celebrity) that are so closely identified with this particular city. There's an intimacy and specificity to Stagg's writing that can make it feel like you're reading dispatches from a friend who knows all the things that interest you, all the things you want to talk about; and there's a fearlessness about exploring topics that are inherently fraught, like power, sex, and the collision of the two as realized in the Me Too movement.

Below, I talk with Stagg about her inspiration for Sleeveless (her last book was the novel Surveys, an unsparing look at the world of social media fame), the ouroboros that is fashion and media, and why she still loves New York.

When did Sleeveless start to take shape as a book? Its mixture of essays and fiction and the way they're arranged makes for such a distinctive framework; what was the original idea behind it?

I don't really know why I decided to do a book. I published my novel, and I was like, Oh no, I haven't published another one. I should try to get something together. And, then I was looking back over some essays, maybe to try to turn one into a book. But, I think it just made more sense to combine a lot of essays and stories and edit them to become a more cohesive collection, and then add some that I had been working on that didn't have a home yet. I think there's only two [in the book] that are unpublished, but the rest are pretty heavily edited from their original form. And, Chris Kraus—my editor—came up with the idea to put them into groups like that. She said it was better than chronological order.

How was it revisiting the older pieces in the book? What was it like going back to the head- and creative-space that you first wrote them in?

At some moments, I guess it was pretty strange, like going back in time... I did have to edit some things, because so much has changed now, and the topics that I focus on are kind of the things that changed the most, like fashion and modes of communication and, I don't know, just the general sort of moods of my niche world. So I had to do a little bit of clarifying or I would have to add dates to make sure it was clear that this was the way I felt two years ago, which is so different [from how I feel] now.

It's such an interesting time period to have to focus on, this era when fashion and media have changed so dramatically. One thing that stands out about your writing is its specificity, which is so present even while you're describing a time that feels so intangible, one that's challenging to pay too much attention to because of how rapidly it changes. What are the challenges that come with writing so clearly about such cloudy, ephemeral things?

I mean, I hope it feels clear—clearer than the actual topics that I'm addressing. That is another thing that I had to look closely at when I was editing essays from a few years ago. Because fashion has a way of sounding really silly when you're talking about something in the moment, but then looking at that same thing, like three years later—or even six months later—[its importance changes.] Also, the structure of the fashion system and the fashion writing system is really dated now, but we've stuck to it for some reason. There's a certain amount of fashion shows every year and there's a certain amount of fashion reviews, and it just gets faster and faster, constantly, until it becomes this sort of strange echo chamber of sorts... it's this strange thing where, first of all, it's paying for itself and not to be trusted. But, second, it just seems completely unsustainable to be constantly commenting on a thing that changes that quickly and intentionally—like, the point of it is to change.

So, writing about, say, an item of clothing that seems really relevant at the time and something that could stand in as a metaphor for trends, it would be something completely different than what it was last year. But, it is what I want to be writing about at the same time. I think it's really fascinating that these trends still persist even though the fashion system seems like it will eventually fall apart. Like, the luxury fashion industry and the way we shop is changing drastically. The fact that the hottest brands are brand-new, that wouldn't have happened like a few years ago. It would have always been some sort of heritage brand [that was big], where the exciting part of the brand was the brand itself. I think people used to care more about shopping for some prestige or heritage brand, and now that social media is as prevalent as it is, it's not as much of a concern. I'm interested in that as a method, as a story and narrative of our culture.

One thing that I feel like I'm constantly grappling with is this idea of both living ahead of the time that I'm actually in, because I have to be so predictive of what's going to be happening and what people are going to want to be talking about, while also being ready to talk about what is happening in the moment. It can feel really head-spinning. How does that sense of time inform your writing? Does it feel like a relief to be able to escape from that when writing a book, something that you know has a longer shelf-life?

I think "release" is the best word for it. I always wonder why more people don't find it as relieving or relaxing as I do to write in a supposedly more literary way. And, by literary, I just mean, when I write, I want the focus to be the language and not necessarily the content; this is me trying to add to the canon or something, instead of reacting to a current moment or trying to come up with some answer to an issue.

I feel like there's a dissociative quality that comes from reading the news now. It's really hard to engage with anything because you feel like you're only seeing the surface of it no matter what you do. When I read a story in the New York Times, in the back of my mind I'm saying, Should I trust it because it's the New York Times? Should I research around it? Should I know more about the writer? Should I at least see people's responses to it on social media?

So, it feels very unstable no matter what to just read or write a think piece or news items, and I feel so much more comfortable reading fiction or essays that have in mind the history of literature. There's some stability in that, where you're just like, this has always been an escape for people, since the beginning. And, that hasn't changed at all. There's never been a moment in history where no one was reading literature. It's maybe less popular than it was, but I find it to be something to hold on.

And the thing about writing something literary is that the intention is to be, literally, thought-provoking rather than just supplying answers. Whereas there's an impulse in a lot of online writing to be instantly definitive in a way that's severely limiting and guarantees it a short shelf-life. Something that I really responded to in your writing was this ambiguity, and refusal to be constantly casting judgment. I mean, there's a lot of judgments or discernments, and your opinions on things are very focused, but in terms of grappling with bigger questions, including things surrounding the Me Too movement, your refusal to engage with the established binary really resonated with me. But, obviously, writing about such complex things can be really fraught. Why was it important to you to engage with topics like that?

I feel like that accidentally ended up being my favorite part of this. I have written a couple of things now that are almost diaristic, what it's like to live in this moment. And, the responses to those have been my favorite to engage with. So many people have told me that they wanted to read something like, not neutral, but balanced about living with these constant reminders of evil lurking around us.

I thought when [Me Too] was going on—I mean, I feel like it's over, it's already over, which is kind of sad—and, I don't know if you've felt this way too, but it just felt so exhausting to learn that a lot of people were doing really underhanded things and they were exploiting people sexually. And, then at the same time it was really hard to learn that a lot of people wanted to attack that system in a way that utilized the exact same method that brought it into place, or that there didn't seem to be a clear-headed response, because everything seemed to just be kind of utilizing the same methods—exploitation.

I think the best response was the story by Mary Gaitskill in The New Yorker ["This Is Pleasure"] that was a fictionalized version of a canceled art publisher. She's kind of the best at that anyway, at seeing the perspective of a woman who is interested in living life as a woman and not fighting, necessarily, the oppression that comes from it, and maybe even enjoying parts of that status. I think that she was the best person to write about this, because it's so complicated when there's never going to be an answer to the question of should power be allowed to be abused in the way it has been.

Because, power is only there to be abused. Especially sexual power, or maybe not especially, but I think all power has a sexual side to it, and vice versa. I actually really like the Me Too movement because of the literature that's come out of it. But, I'd heard so many responses—not written ones—that just seem so uncharacteristically close-minded, and so I just felt like I had to respond to it myself.

The reality of power is, as you said, that it is always going to be abused. This goes beyond Me Too, of course, and touches on another aspect of your book, which is the power of celebrity, and proximity to celebrity, which is something that you have had a lot of as a journalist. How do you think writing about celebrities and interviewing them has informed the way that you write essays or auto-fiction or anything in which you're a part of the story? How has it informed the way you present yourself to the world, now that you're used to presenting other people, famous people, to the world?

I hadn't thought about it, but I'm sure it's affected the way I present myself to the world, being around people whose job it is to present a self to the world in new and interesting ways. I think I'm still fascinated by celebrities, but in a way that is more interested in how anyone could possibly want to be one at this point—just because it seems totally exhausting and like the rewards are very imbalanced now with what gets lost.

I guess it's affected me in the way where I understand that, when you become famous now, you have to constantly define yourself in a million different ways to a lot of different audiences that might have different ways of interpreting those definitions that you've decided on. So, you're kind of in conversation with an anonymous chorus about who you actually are as a person. And that, to me, sounds hellish. I have this fear of overexposure.

And, now, I actually hate interviewing celebrities. I think it's boring and usually disappointing, and they're completely packaged by their agents or their publicists. I think about the way that must suck for them, and also the way I don't ever want to be obsessed with it again.

What are you working on now? What's the next book you'd like to publish?

I would love to publish another novel, and I would love for it to be not necessarily about social media. I think I have this kind of preciousness about writing, that I think of it as a salvation in my life. I don't want to always be writing things that feel like they're in response to something else.

I don't have the dream anymore of being a celebrity interviewer or whatever; it's what I thought I would want to do when I moved to New York, and now I have this almost completely backward way of thinking about my writing now. The next thing I write, hopefully, will not in the present moment—I'm not going to write historical fiction, but I just want my writing to feel the way it felt for me when I discovered that I liked to write in the first place.

Is there anything you would go back and tell yourself about writing, like, the you who was just about to move to New York? Advice is maybe the wrong word, but is there anything you'd want to convey about this career path?

I don't know. I think I've had a pretty good run. I really liked moving to New York, and I moved there to be closer to my sister, and I think that was worth it. And, then I made such good friends right away, and it was pretty easy. I think maybe I've had rough times with dating, but it's kind of worth it, because I really like all the bad dates for the stories that they ended up getting me. And, I guess yeah, sticking around too long with certain people was not the best idea, but I don't know, I'm dating somebody that I love now, it's all worked out in the end, and I really love my job right now and I love how much I get to travel. I think I wouldn't really change that much, actually.

Yeah, you've done a really amazing job. It doesn't seem like you would have any regrets. And, in fact, so much of this book seems so generous to your earlier self, and to New York and to that life, even if it's full of flaws, or almost because it is. I really like how you call New York out, as being an actor that's always playing itself. It felt like an acknowledgment of how simultaneously special and strange and phony and authentic living in this city always is, even if we're always told that we've missed out on what was good.

A common interview question on podcasts is when somebody asks, you know, if you could live in any place at any time, [what would it be]? It's like there are certain eras that are really valued as moments for art movements or whatever. But, that's such a boring way to live your life. And, it's a really interesting time to live in right now. And, I think New York is really interesting right now, and I wouldn't be surprised if it was kind of made into a nostalgic culture later on. There's a really interesting way people have started talking to each other and dressing and communicating, and it feels like everybody's sort of in on some big joke that I love. I feel like there's this weird, fun thing happening in New York, where everybody does feel like they're creating a narrative that will be remembered. There are very complex conversations happening with very young people. And, it's funny, I think it's a great time to be living where we do.

Sleeveless: Fashion, Image, Media, New York 2011-2019 is available for purchase, here.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.