Next Gen: Women In Rock

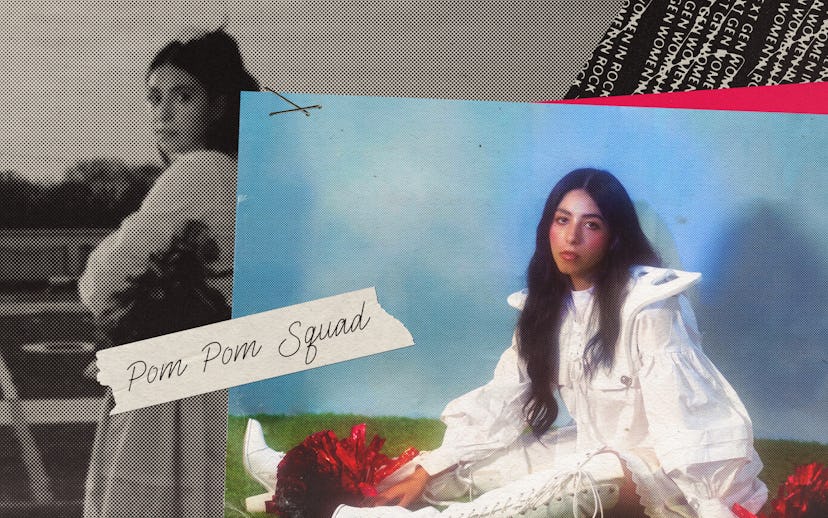

Pom Pom Squad Gives You Something to Cheer For

Meet Mia Berrin, the force behind Pom Pom Squad — and one of 2021’s fiercest new albums.

When Pom Pom Squad’s Mia Berrin was a teenager in Florida, her image of music stardom wasn’t a sold-out arena tour with so many fans that their faces blurred together. It was the fairy lights, tattered carpet, and close quarters of Brooklyn underground institution Shea Stadium, a place that embodied not only the authenticity of her guitar-driven tunes, but the find-a-way-or-make-one mentality that she has applied to every facet of her career, from songwriting to production to costume design to videos.

“When I was growing up in Orlando, indie bands and DIY bands were like celebrities to me,” she says. “I moved to New York and I started going to shows and seeing all of my favorite artists and it was really cool. Also I was like, ‘They’re just people. They’re just 20 year olds…’ It felt way more attainable.”

On Death of a Cheerleader, Pom Pom Squad’s recently announced first full-length album, Berrin sounds like an artist capable of bringing that DIY ethos and charm to venues that can fit thousands. Early singles “Lux” and “Head Cheerleader,” both of which were produced by Berrin and indie critical fave illuminati hotties, showcase her duality. The former is urgent and jagged with riot grrrl-style shouted vocals, while the latter is a finely-tuned piece of fuzz pop that represents a similar sonic breakthrough to the one Phoebe Bridgers had with “Kyoto” this time last year.

Here, Berrin speaks about broadening the Pom Pom Squad sound, the work it took to craft her debut album, and the fraught nature of describing music as “diaristic.”

Your 2019 EP Ow is more four-piece rock band, a lot of guitar and bass, but this new record is more varied. Did you want to branch out the band’s sound?

I think not intentionally. I’ve talked about it a little in the past, but I actually went to school for production, partially. When I was in school, I was learning how to produce strings and work with an arrangement. It’s funny, because at the time I didn’t think I needed it. I thought, “Well I’m the girl who plays in a four-piece band.” There were so many pop people around me or people who were more centered on pop production and pop aesthetics. For some reason, when quarantine started, I was listening to a lot of Motown and childhood favorites and I just kind of realized that was the instrumentation that really appealed to me.

Now knowing you had the Motown sound in your head definitely explains some of the record’s flourishes.

Also around the time of everything happening with George Floyd, I started thinking a lot about equity in the industry and the exploitation of Black artists specifically in the ‘50s and ‘60s with these cover songs. There was this weird realization that rock and roll was invented by a Black queer woman [Sister Rosetta Tharpe]. She was the pioneer of the electric guitar sound. I grew up as this outcast weirdo for liking guitar music and punk music. It was a moment of clarity where I asked, “Is there a way to work off both of these things at the same time? Both of these aesthetics at the same time?” Ultimately, the album is f****** whiplash from genre to genre [laughs].

I know you have a bit of an acting background, but were you always thinking about how things would translate from music to corresponding visuals?

I think the first thing I started thinking about was all the music that I was inspired by. Listening to riot grrrl and the grunge scene and glam rock and all these people who dressed up to do this thing, that became exciting to me. My sister would take us to go see Britney Spears. I think my first concert with my brother was Fall Out Boy. That’s my first concert that I was conscious of. I never realized what’s interesting about seeing a band play is just that they’re all playing their instruments live. To me, that’s no more interesting than hearing a pop star sing to a track. It feels like an equal amount of work, so I expect more from a band playing than just to stand onstage and play. I want to see a show. So, when I thought of starting the band, that was my first instinct, that we were all gonna wear matching outfits and do this, that, and the other. I was taking pictures with my friends from high school on the football field and making those album covers.

How did you ultimately pivot from attending acting school to pursuing music?

Basically, the reason I ended up going to music school is that in the middle of being an actor, I was on a short film set — here’s the Pom Pom Squad origin story, for the clinical part of the interview. [laughs] I was in acting school and I was doing a short film. It was these two dudes who wanted to do a movie about a party and so they thought that the best way to do it was to have a giant party two nights in a row.

That’s a classic college short film move.

There were these dudes that were trying to talk to me. They were like, “We’re musicians. We play in a band.” And I was like, “That’s so funny, because I’m a musician. I play in a band called Pom Pom Squad.” I totally tried to big-man these two dudes. I had taken the name Pom Pom Squad on Bandcamp and Instagram and done the whole thing. When I was 17, I wrote a couple songs, including “Lux.” They were like, “Well, show us your band.” I said, “OK!” I sent them my Bandcamp and life went on. And then one of the guys texted me a couple months later and was like, “Your stuff is actually really cool. I would love to produce some songs for you.” That’s how Hate it Here, the first EP that we did, happened.

So then I was skipping classes to play shows and not learning my lines and getting s*** on by my teachers. One day I was like, “I need to get the f***out of here.” And I did. I got into music school and I think that education was good for me, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do and how I wanted to do it. I just geared my own education towards Pom Pom Squad and put everything into that.

In five years, what will you want to have had happen in your career for you to feel good about the early stages of Pom Pom Squad?

I don’t think I’ll ever be satisfied with anything. How could you be? I think you can only be satisfied enough to feel comfortable sharing something. I used to hate when artists said this but now I understand it a lot better. I hated when artists would be like, “I don’t like this or that song.” It’s your favorite song by this artist and they’re like, “I hate this song. I can’t stand it.” For me, I don’t hate anything that I’ve done. There are things I feel closer to than others. I’ve journaled a lot since I was an early teen and have a clear document of everything I was going through at a certain time. I do really have a lot of empathy for my past selves, but I also have to look back and say, “You could have done this better.” Here’s what you learned, essentially. As long as there’s always something new to learn about music and about the creative process and about visuals, I don’t know if I’ll ever be like “Wipe my hands clean. I’m done.” Making things is how I process.

Particularly on this project, it was really just a colossal undertaking for me and everyone else. To see it in front of me and be able to break down all the pieces and say I know how to reverse engineer it is one of the few moments where I allow myself to look at what I did and be proud of it.

Which is a scary feeling. It’s always easier to downplay that and be self-effacing. To do something as big as make an album with all the corresponding pieces, you’ve got to be proud of it, to a degree.

I think I spent so much of my life apologizing for existing. Especially being a person of color, being a queer person, being a woman. It’s always been easier to apologize than to take up space and assert that I deserve to do that. Sometimes when I tell people I studied production, something as simple as that, which is just a fact, I’m told, “You’re full of yourself.” It’s often getting talked about as the little girl who writes in her diary and it’s just a coincidence that this happened for me. It’s not. The things that you say about yourself affect your mind and so if you’re constantly telling yourself, “Well, maybe I don’t deserve to take up that space” or “Maybe I am just shooting from the hip and this is all luck or the people around me,” then you’re gonna think it’s all the people around you. I still have trouble calling myself a musician. I still feel like that’s not a title that I deserve to give myself.

How do you feel about the way your music’s been covered? Do you think people are getting at the heart of what you’re trying to do? Are there ways the conversation could be improved?

I’m interested to see how the record cycle goes with this new project. With Ow, save for a select few write-ups, I did feel like it was pretty spot-on. People genuinely got it… The one thing I don’t feel great about is, as I said earlier, being talked about like, “It’s all ripped from the pages of her diary.” It devalues any effort that goes into it.

I remember there was a write-up about Car Seat Headrest and the wording was like, “He crafts a brilliant narrative based on his own life,” which is putting the action on him. He crafted something. There was a write-up about Julia Jacklin around the same time that said, “she’s this vulnerable, diaristic writer.... she is this” rather than “she crafted this.” These are just examples that came to mind–they have nothing to do with the artists themselves. I think it just gives me pause that I don’t often see the phrase “diary” or “diaristic” associated with male artists.

There’s more acknowledgment by the media of the separation between a man’s artistic persona and his personal identity than with musicians of different genders.

Especially being in the genre that I’m in and being a person of color, it feels even more like a blow, because I’m already getting less — or in the past was getting less — than a person with the same sized band who’s white. To get what I can get and still have it be pejorative is hard, and it’s something I try to exercise perspective over, but it’s this tough balance. I always want to be the person who starts the conversation saying, “Why is this the way that it is?” or “Have you thought about why you’re writing about women that way?”

There have been some successful moments with that, but the other side of it is that I end up feeling really drained emotionally–being the person who’s not in the position of power usually in these exchanges, who has to temper my own feelings and expectations. I’m interested to see how this album cycle is handled, because I feel like there’s more to be explored here.

You drew that distinction really well, the difference between “crafting” and “is.”

Songwriting is really hard. I can count on one hand the amount of songs that just happened to me. All of them require a level of sitting down at your desk or with your guitar consciously and saying, “I’m gonna finish this song,” and writing out the structure.

I was talking to somebody about resenting when people are like, “Well, I don’t want to be defined by my identity as any part of my music.” I wish that I had the luxury of not being defined by my identity. It’s written on me. There’s really no way to hide that–or, there is, but it would involve making the choice to conceal a lot of myself. I did that for a while and it’s tiring. For better or worse, I’m glad that I can be that visible, because there are so many people who look like me or who are of marginalized identities who see me and are like, “That’s music that I can find a home in.” That’s not exclusive to marginalized people, but if I have to be a symbol to somebody that they exist, as silly as it sounds, I’ll do it. That’s not something that I feel resentful of, is people needing to see me to feel valid in their own life.

One of the other artists in this package, Jensen McRae, talked about the thing that’s always happened to Black folk artists, which is that they get described as making R&B, even though their stuff doesn’t sound like that at all. Do you feel like you’ve dealt with misconceptions about your music?

When Pom Pom Squad first started and I was playing in New York, I got booked on R&B bills. If you went on the Pom Pom Squad Bandcamp, let’s just say you were a totally objective party. There’s only one thing on my Bandcamp that would cause somebody to go, “Huh, she might be an R&B artist.” And it is literally that I’m Brown and nothing else. It was such a sign that you just looked at a picture of me and said that was R&B.

Is there anything else either about the new record or yourself as an artist that we didn’t hit on?

It was exciting for this album to incorporate a lot more of myself than I have before. I had a very distinct emotional journey a couple years ago, where I really came into myself as a queer person. I always talk about it like stepping out of an old skin. It just felt like the world turned one day and I realized I was living somebody else’s life. I wasn’t living my own life. I still have to edit myself in many ways, because it’s just how I exist, but I think I was able to explore my three-dimensional self more than I ever have been. It made the artistic process more difficult, because I was like a whole new self, so to speak.