Entertainment

Does Pop Music Need Pettiness?

When stars collide, it could be good for business

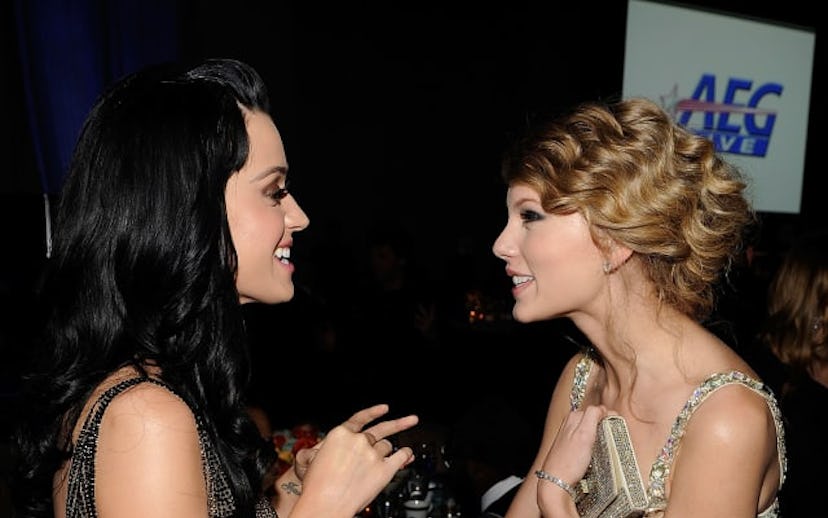

If we never heard another word about the Katy Perry-Taylor Swift feud, it would probably be too soon. Since Perry reportedly “stole” Swift’s dancers back in 2012, we’ve been treated to a constant stream of she-said-she-said rhetoric, which was parlayed into two Top 40 singles, thanks to “Swish Swish” and “Bad Blood.” It's almost as though the whole thing was part of a genius business plan.

We get it. We get that the singers don’t like each other, that they’ve figured out how to monetize it, and that their feud is being milked for the sake of publicity. It’s gotten boring, but it’s par for the course. Pop music needs pettiness.

Of course, there’s a difference between bullying and pettiness, so it’s important to note that both Perry and Swift have embraced the latter. Yes, they’ve written (bad) songs about a situation that happened five years ago, but outside lyrical shade, they’ve kept acts of aggression relatively professional. On the same day Perry released her new album Witness, Swift released her entire back catalogue to streaming services. Then, Perry used a conversation with Arianna Huffington on her live feed to say she forgives Swift and is ready to let it all go. Neither has even insulted each other outside the Lauren Conrad school of confrontation, using lines like, “She knows what she did,” to stoke the fire. There haven’t been comments on anybody’s looks, dating life, or anything outside the spectrum of the industry. And it’s worked because here we are, talking about it.

The point of pop pettiness isn’t to create an engaging narrative, it’s to keep us talking in general. So while “the Perry-Swift feud needs to die” conversation is alive and well, it’s still a conversation that we’re sustaining. It’s performance art that we’ve chosen to consume.

Which has been a defining factor in the pettiness that’s dictating pop music. I mean, Liam Payne never slagged off One Direction in the immediate wake of its hiatus, but he used his solo debut last month to say he was finally “free” from the band. (A direct contrast to Harry Styles and Niall Horan who used their solo debuts to sing the praises of their time in the group.) But every story needs both a hero and a villain, and Payne stepped up to take on his role; had he joined the choir of One Direction supporters, the band’s breakup would make less and less sense. Because if everyone had been so happy, why would they have split up in the first place? (Exactly.)

In the same realm, Camila Cabello hasn’t shied away from the drama that’s been defining her exit from Fifth Harmony. When being asked about the group’s new single, she gave an answer on par with Regina George complimenting somebody’s skirt, while the band itself has stuck to a message of togetherness by telling fans that they’re now the fifth member of the group. (And that they don’t have plans to change their name.) It's passive-aggressive but works enough to build a story: Camila’s gone, she—like Zayn Malik, post-1D—is happy about it, and Fifth Harmony never needed her anyway.

Add to this Justin Bieber’s dismissive reaction to The Weeknd’s music after news broke that Abel Tesfaye was dating Selena Gomez, and any and all 2017 feuds seem to be focused squarely on a nemesis’ professional offerings. When played out in public, it drives pop consumption en masse. We end up listening to “controversial” singles or throwing our support behind an artist whose standpoint we can get behind. And this isn’t a bad thing; it’s not like we’re rallying behind insults or bullying, we’re simply supporting the industry that all parties involved belong to.

Plus, we’re entertained.

One of the best things about pop music is the way it makes us feel a little less alone. We relate to lyrics and to backstories, and social media makes artists more accessible. So when they get petty, we see our own experiences and our own capacity for pettiness reflected in their feuds—similar to the way we relate to movie or TV characters we love. And since pop stars exist on their own plane, their drama morphs into performance art in which the only thing being affected is their artistic offerings. It’s not personal, it’s business. So it’s safe for us to encourage it (since no one is getting hurt), take sides (because our allegiance will drive sales), and engage—even when it gets boring. (“Swish Swish” came out three years after “Bad Blood,” and here we are, talking about how long this feud’s been going on for.)

As we’ve gleamed from Swift and Perry, pettiness in this form can feel stale. After a while, nobody wants to hear about stolen dancers or band break-ups or why Bieber thinks The Weeknd’s music is “whack” for more than a handful of years. But that feeling of “ugh” doesn’t signal the end of an artist’s relevance, it signals the third act of a very calculated timeline: Once the pettiness subsides, the apology tours begin. And pop artists begin to collaborate, reunite IRL, or drop surprise singles that squash the beef we’ve been actively engaged in, peaking our interest all over again. Pettiness serves a purpose.

And we absolutely love it.