Entertainment

'Go Ahead In The Rain' Is A Powerful Homage To The Ultimate '90s Group

Talking with Hanif Abdurraqib about his love letter to A Tribe Called Quest

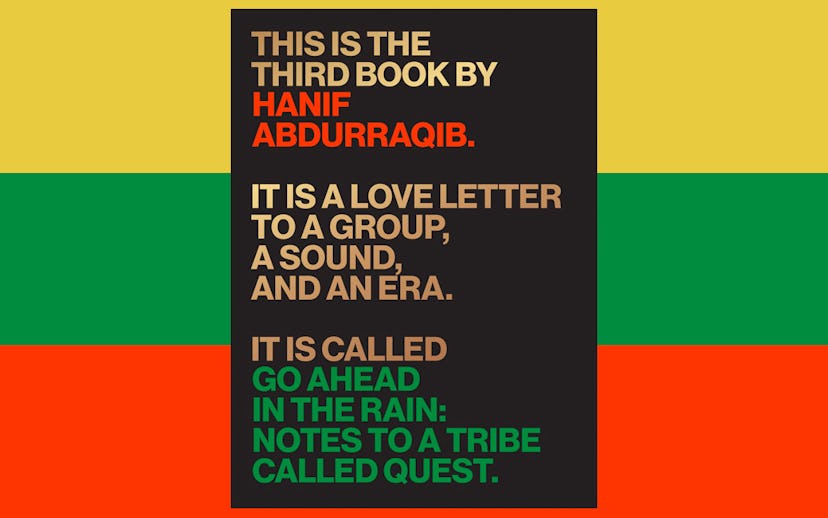

Hanif Abdurraqib's new book,Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, bills itself as "a love letter to a group, a sound, and an era." It's a fitting description for a book that's just as much about the emotional space that the legendary hip-hop group created for Abdurraqib as a teenager than it is about the music itself. Abdurraqib, whose 2017 essay collection They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us was widely praised for its thoughtful meditations on musicians as diverse as Fall Out Boy, Marvin Gaye, and Carly Rae Jepsen, uses Go Ahead in the Rain to do the same for A Tribe Called Quest, and explains why they've remained important to him today.

As Abdurraqib writes, the group's aesthetic, which leaned heavily on jazz sampling and a matching sense of continuity with the Black musical tradition, helped to define the group as "both uncool and desirable all at once." For the awkward high schooler, trying to fit in in the footsteps of a popular older brother, their approach resonated with his own development: "They, too, were walking a thin line of weirdness: just weird enough to stand out from their peers, but not so weird that it seemed to be contrived."

Go Ahead in the Rain is peppered with letters that Abdurraqib writes to each of the group members, as well as to Phife Dawg's mother Cheryl Boyce-Taylor, who watched her son die of diabetes in 2016, just months before the group released their final album, We Got It from Here… Thank You 4 Your Service, their first record in 18 years. In his personalized approach to the group's musical legacy, Abdurraqib articulates how the group helped to define his personal growth, helping readers appreciate the power that our favorite acts have in helping us create a durable sense of identity.

NYLON caught up with Abdurraqib to discuss why he included other '90s rappers in his book on the group, how the group's final album balanced anger and grief in the wake of Trump's election, and how Abdurraqib hopes to honor Phife Dawg's legacy.

What was it like for you to write about this group that was clearly formative in your experience with music?

I think so much of the process for me here is the same process when writing about music in general, which is trying really hard to articulate a fan experience that is rooted in both reverence and accountability, and trying to be nostalgic but not irresponsible with nostalgia, and what our feelings of nostalgia afford us about how we view the world. Instead, trying to use nostalgia as a tool to talk about bridges being built toward our own growth, and how I've been fortunate enough to have these musicians show me a path. So I went into it with this mindset of wanting to write a very long and sprawling generous thank-you note to a group that helped me build a lot of bridges out of my own awkward childhood into an awkward adulthood.

That sense of generosity is also an important part of being accountable, recognizing that everyone is imperfect. I think about that in the way that you talk about learning about Phife's death from diabetes while biting into a cherry chocolate.

I think often about how writers and fans honor musicians while they're still alive, and I really didn't do a good enough job honoring and loving and giving Phife his roses while he was still here. It's just the way life is: Life is somewhat unexpected, and because of that, by nature, we don't honor the living until they are no longer living, and I think with Phife I really missed an opportunity to honor him well, so I tried to make up for that.

In the book, you're not only writing about the group, but also the era they come up in in the '90s, and obviously that's also you writing about your childhood. What did it mean for you to put it into this context: for example, Q Tip being very inspired by Dr. Dre's production while making Midnight Marauders?

In my mind, they're part of a larger ecosystem of hip-hop. Tribe, and Native Tongues in general, were kind of pacesetters for a type of hip-hop aesthetic, but it felt irresponsible to not represent how they arrived there, or not represent the entire national ecosystem of the time. I don't think anyone can write about an album like Beats, Rhymes, and Life without writing about how that album was the first one where Tribe was responding to the times and not setting the pace for the times. But that didn't happen out of nowhere—it was a slow build toward an end result.

I didn't want to write a straight-line biography, because I didn't want to present myself as an expert on the group. I'm a fan, but I'm not an expert. Even with that in mind, it would feel irresponsible to not talk about how I think Mobb Deep is kind of Tribe through a looking glass, or how the emergence of Wu-Tang warped the idea of what a rap group could be, or how N.W.A. was doing live recording narrative work in a way that Tribe was doing inside of a different geography. All of these things are part of a machine that really drove home the point that Tribe didn't exist in a vacuum, and they didn't grow in a vacuum.

I was also struck by how you talked about tapes and CDs, and how they shaped your music listening experience. How have more recent evolutions of music technology impacted your relationship to this group specifically, and music listening more generally?

I do appreciate the convenience of streaming. I think it's useful for me to have music at my fingertips as someone who loves it and is often immersed in it. But I think there's a very simple one-to-one in thinking about the idea that there are musicians that made music in and for a different era, and therefore the most excitement I get is listening on devices from the era.

With cassettes, for as much as I kind of romanticize them in the book, I try to be honest about them—they're perhaps the most inconvenient form of music listening in my generation. What was convenient about them was that they were compact, but Walkmans were bad, tapes were more fragile devices than other, the tape would get caught, and you'd have to wind it back up. I'm not into cassette tapes, although I appreciate that there are bands now on cassettes. That's wonderful, but I don't have a cassette player in my general vicinity.

I still like the sound that a needle makes when it first touches itself to a vinyl record. I like the popping and the crackling sound that's made before the song starts, and I love when the needle finds its way along a record's groove. When a record is played all the way through, there's something sonically pleasing about that. Especially for Tribe, there's a way that listening to them on vinyl fills a room differently. The room is filled with every sound that's been put into the music. When a group sampled that much, had that many elements happening in one song, especially in the early records before the sample laws changed, it kind of demands the filling of a room. That, or headphones. I think with Tribe, it has to be an intricate part of the room's architecture, or an intricate part of the architecture of the ear, where all of the nuances jump out.

The group came back in 2016, to the surprise of pretty much everyone, in such a beautiful and heartbreaking way. In the book, you talk about the record coming out two days after the election, and the impact that it had in that moment. For you, what did it mean to see them return in this frightening and confusing moment?

I think that I find myself most thankful to hear an album that was colored with what was an appropriate amount of anger. I think all the time about how that album balanced anger and grief, which became one and the same. Grief is but a short turn of the head away from anger, one body of water flowing into the other. I think they're very close, so to see an album that really manages that well was wonderful for me.

I didn't know what to expect of a Tribe album in 2016 after not having one for so long, and part of that is because Tribe's early career is so timeless: those songs, those albums, feel like they could have come out in various different eras. When you're a group that's ahead of its time, I think it's a bit hard to make something that feels like you've grown or changed, and I think that we got an album from Tribe that was one of adults who looked at the world they were stepping into and were fed up with it. I really valued that.

Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest is available for purchase here.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.