Culture

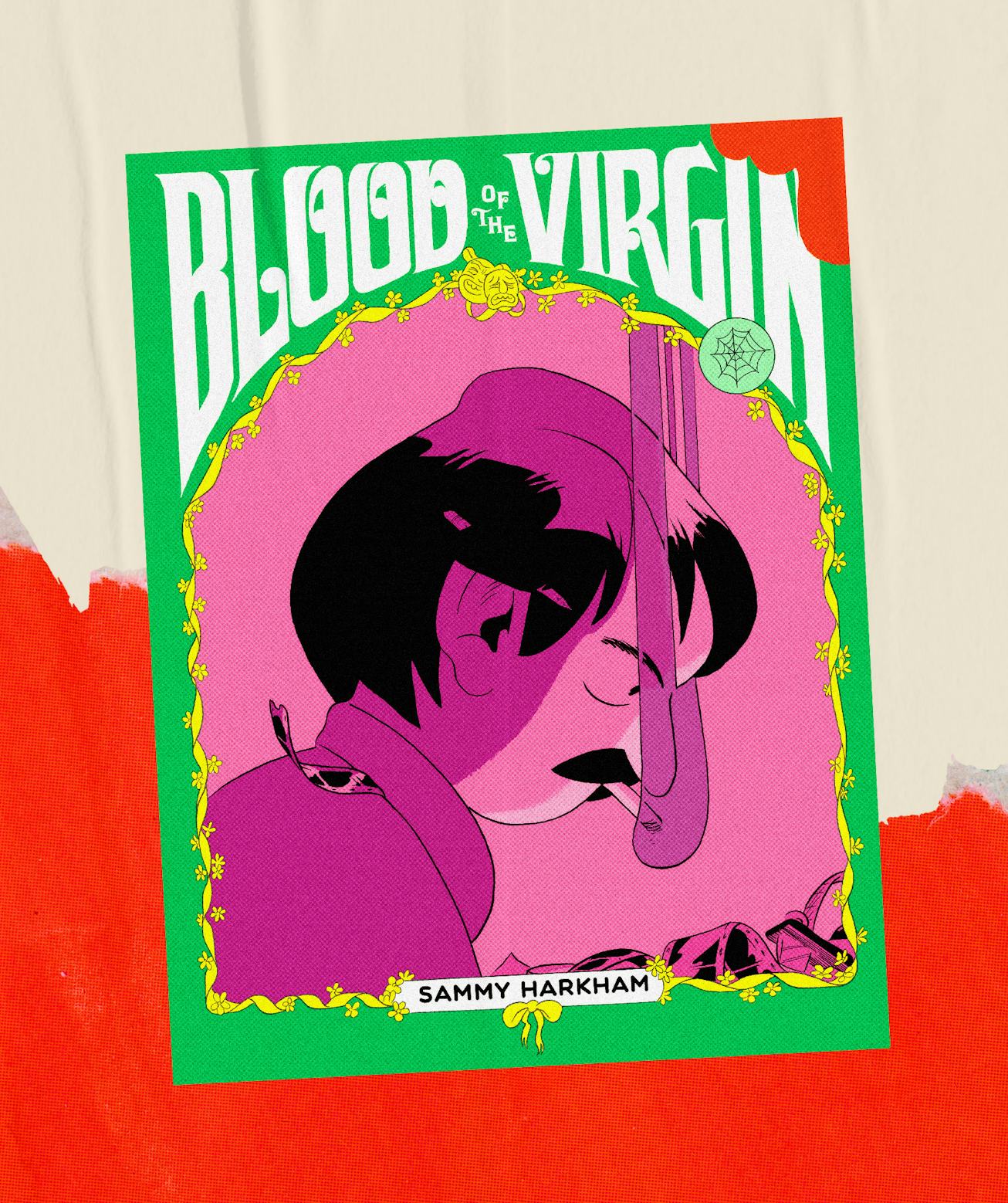

Cartoonist Sammy Harkham Brings ‘70s Los Angeles Grit To Blood Of The Virgin

The “romance comic” is a nearly 300-page magnum opus that immerses the reader squarely in 1971 Los Angeles.

The “romance comic” is a nearly 300-page magnum opus that immerses the reader squarely in the era.

For the last 14 years, Sammy Harkham has been immersed in the gritty world of 1971 Los Angeles. A lot of creation requires immersion, but few less so than writing and illustrating comics. This is especially true for Harkham, who created, scripted, drew, and inked thousands of panels to create his nearly 300-age magnum opus Blood of the Virgin, a sweeping, surreal, and addictive graphic novel about the triumph and heartbreak of artistic ambition.

The story follows 27-year-old Seymour, a Jewish-Iraqi immigrant film editor for exploitation movies who gets a chance to direct his screenplay “Blood of the Virgin,” in 1971 Los Angeles at the dawn of independent filmmaking. It’s a dream come true, only his personal life, with a new baby and wife at home, becomes increasingly fraught and upended by Seymour’s singular drive. If it feels like fodder for a Safdie Brothers film, you wouldn’t be the first to think so: Josh Safdie counts himself among fans and contributed a blurb to the book.

But it isn’t a love letter to this time and place; Harkham’s impulses are less rosy-tinted than that. Harkham was largely inspired by his parents’ relationship: His father is from Iraq and his mother grew up on a dairy farm in New Zealand, and the two wound up in Los Angeles in the ‘70s.

“I would talk to my father and he would tell me about being an immigrant in LA with a young wife and a newborn baby, and not having a dollar and trying to just hustle something together. I realized that as he would tell me these stories, there was all this other stuff I knew that had happened in his personal life that he was not talking about at all,” Harkham says. “ So it was very funny to me. He's talking about overcoming struggles, while in the meantime, he's having serious marriage problems. It sparked something as far as a romance comic.”

Harkham continued to be fascinated by the idea of a romance comic — but he couldn’t think of any.

“Even though we think of Roy Lichtenstein and his famous paintings of very melodramatic women with the single tear wondering about where their husband is or whatever, we actually can't think of the roots and the influences of those paintings,” Harkham says. “I think it's useful to not know where you're going, but because if you're driven by images and ideas that you don't understand, then you keep exploring them because your brain keeps popping them up because you can't let them go.”

NYLON spoke with Harkham about a long game creative process, the alternative comics that inspired him as a kid, and how he became enmeshed in ‘70s LA ahead of the book’s release.

Blood of the Virgin is available from Pantheon now.

You spent 14 years on this book. How does it feel having it out in the world now?

It feels good that it's out. It felt less like a project that needed to be done, more like part of my daily process, more like being a gardener where you slowly tend to your garden. The growth is so incremental that you just have to live with it and you can't be hung up on finishing it.

The benefit of that is that you make every page count and just live inside it. In many ways, the history of cartooning is people spending decades working with a group of characters, but it would be, let's say, through a daily or a weekly strip, so I tried to embrace it. Now that it's done, I couldn't be happier. I think the book is really beautiful, and I've never published anything and felt good about it. Usually I cringe inside and then I hide the book for a year, and then maybe in a year, if I'm lucky, I'll see it and I'll be like, "Oh, this isn't so bad." But with this book, I was shocked how well it turned out. I'm proud of it and I'm happy for people to discover it.

I love that metaphor of it being a garden that you're tending. People often want to just get to the end of a creative project instead of seeing it as part of what you do every day.

You can't ever expect anything from an artistic endeavor, especially the one that you're taking on your own. It’s got to be one of those things where making the work itself is the reward. You have to find a way to come to terms with it and try to kill your ego and not worry about if anyone will even publish it. Because here's the thing, if you rush it to get it done, who are you benefiting? You're not benefiting yourself and you're not benefiting the reader. I realize I definitely had myself on deadlines, but it was more about that being part of the process. I think that's more psychological than anything else.

I would imagine that also helps with not spending so long on one panel, too.

That's right. I had a basic shape of where [the drawing] was the first day, so I would be writing the page out. I don't write a script, so I would be laying out the page and figuring out the rhythm of it. The second day would be figuring out the penciling part, and then the third day is inking. I realized that inking is very much a performative act, in the sense that it's almost like pressing a record on a reel to reel tape that you can't waste. You'd get to the end and you just hoped it was good enough, because there was no way I was going to then redo the whole thing from the beginning. I'd like to think that when you work that way and you're trusting your intuition, that even someone who's not aware of your process, when they read the work, they can feel that there's something unique about it. There's something special about it, that comes through either in the writing or just the shape of the thing.

I read your New Yorker interview and there was something that you said that I can't stop thinking about, which is “how the authorial voice of a cartoonist has a rawness and a clarity that is almost unnerving.” That kind of sounds like what we're talking about.

I'm 42, so when I got into comics as a teenager with alternative comics, it felt like a whole world, but really it was half a dozen artists, like Julie Doucet, and Chester Brown and Dan Clowes, Renee French. There's a couple, not many, it seemed like a lot at the time, but there really weren't many. And there was this sense that when you read these people's work, you were seeing all of them in a way that wouldn't even be revealed by meeting them. You realize that there's something about the way they're drawing, because they're all self-taught and they're making work that doesn't make them any money, but they're very passionate about it. They're unintentionally revealing things. Even when they think they're revealing, it's like, no, you don't realize that the way you draw these faces in the background, it says more about you and the nature of your psyche than anything.

I think one of the most fun parts about this story is the setting: a gritty 1971 Los Angeles. What drew you to that?

I think because I don't know enough about it, and I wanted to immerse myself in it, but I didn't want it to look like Austin Powers. Comics are a funny medium in that it deals in types, visual types. So a hippie would be flares and a headband and John Lennon glasses, and you'd be like, that's a hippie. You can absolutely embrace that stereotype and go and explore. You could start with a stereotype and then push deeper into it.

But with this comic, because I wasn't really working in that mode. I was more thinking, what does a telephone look like? Why are people's names different, in '71? Naming the characters was really important. It was a weird thing like that. There were tons of things that felt familiar and felt different. I liked being able to just subtly show those things while the story was moving.

I never tried to wink at the reader, or be like, look how dumb people were back then. And look how much more evolved we are now. Or even the flip side of that, I definitely didn't want it to be nostalgic and romantic for this sort of Boogie Nights or Once Upon a Time in Hollywood thing. It's not a love letter to time. I wanted to get so deep into the world of it that the reader could almost smell it, just the scents of the room.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on