Culture

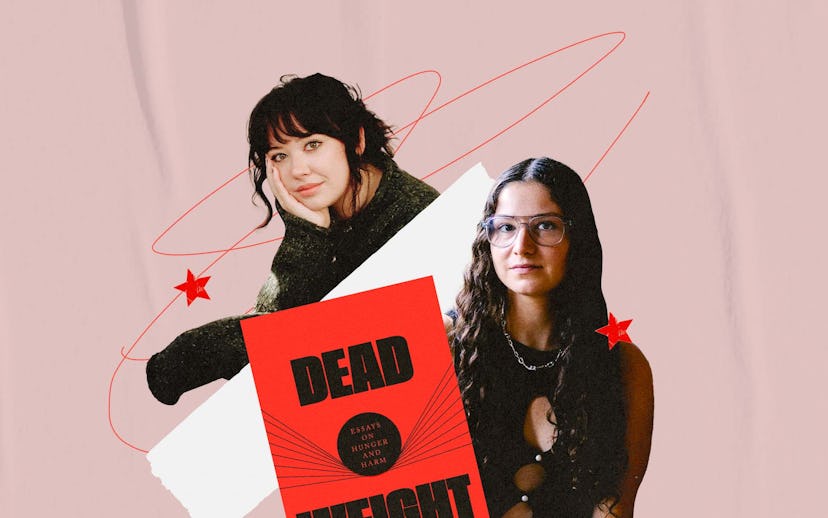

Emmeline Clein & Rayne Fisher-Quann Want You To Deconstruct The Western Beauty Standard

The two writers discuss community, liberation, and “respect for sick and sad young women.”

Whenever Emmeline Clein talks to a woman about disordered eating, the immediate reaction is almost universal: What woman doesn’t have an eating disorder? Admitting that horrifying fact, she says, is a powerful first step to recognizing the life-and-death consequences of a disease that harms — to some extent — the majority of the population.

“It doesn't have to be this way,” says Clein, who for the last five years has been working on her eviscerating debut book Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm. “But if we keep having this culture of silence around it, then it’s going to be forever.”

An assiduously researched and urgent debut book, Dead Weight is both a collective memoir of girlhood and a blistering take on the need to abolish the Western beauty standards that actively promote self-harm. Among those interested in Clein’s work is the writer Rayne Fisher-Quann, whose debut book Complex Female Character, an essay collection charting the strange problems of self-commodification and objectification that go along with modern womanhood, is forthcoming from Knopf.

“Everything about it really spoke to me,” Fisher-Quann says. “Like many women — spoiler alert — I've had experiences with eating disorders and I think a lot of women have been craving a book like this that is smart and sharp and speaks to us on the same level and gets it in a way that a lot of other media doesn't.”

Below, Clein and Fisher-Quann discuss the political and moral urgency of deconstructing Western beauty standards and how the catharsis of community can be harnessed as a tool of hope and action.

Rayne Fisher-Quann: How are you feeling now that the book is out there? The thing I'm most scared about for my own book is the point when I can't change it anymore. With internet writing, there's so much control you have over it. A book is such a physical object that's now in people's hands.

Emmeline Clein: Completely surreal. Both thrilling and terrifying for exactly the reasons you mentioned. I think both of us have been writers only in this internet era. The lack of control is definitely terrifying, but in a sort of cringingly beautiful way, I'm trying to think of it as a metaphor for trying to have less control over my body and the way that I am perceived, whether that's in my physicality or in my thoughts.

RFQ: So much of learning how to handle specifically being a public-facing woman in any way, whether it's your body or your work, is internalizing this idea that how other people interpret me isn't my business.

EC: It's such a journey because as a woman, you're socialized from the minute you're cognizant of what other people think that it is, in fact, my only business.

RFQ: A thing I really connected with in your book is this idea that having an eating disorder isn't actually crazy. It's actually the most logical possible response to the very explicit messages that everybody is sending all the time. What I have always found so maddening about eating disorder recovery is that it actually feels much more crazy to get better from an eating disorder. You have to have a level of true cognitive dissonance.

EC: You feel like you're living in an alternate dimension in eating disorder recovery. The type of recovery that I've been through, and probably you've been through, and most of my friends have been through, which is not the sanctioned type — in those settings and in a lot of books about eating disorders, you feel like you're being rational, but you're being told that you're crazy. The narrative is: You're a feminist, so you should know that being thin isn't actually that important. At the same time, they are going to put all of this emphasis on calories and on you eating in an incredibly weird, theatrical, regimented way. The ultimate goal of treatment should be to be able to endure a society that wants you to have an eating disorder without resorting to those behaviors as coping mechanisms.

I find it so much more cathartic and liberating to think of it as: Society wants you to be thin to a degree that requires self-harm for most people. It wants your eating disorder to take up so much of your brainpower that you actually don't have time to think about a lot of other political, social, and economic issues. That is not a failure of yours. Once you can realize that you've been reading the room that you're locked into correctly, I think that's when you can get the key to exit that room.

“Our society not only wants us to be thin, but also doesn't want us to be friends with each other because if we're truly honest with each other, then we might realize that we don't want to be in this beauty competition because it's hurting so many people we love.”

RFQ: A thing that you talk a lot about in the book is a real tangible solution: a community, which is again, something that is actively discouraged by a lot of eating disorder scholarship and treatment.

EC: You need to find a will to live in a society that doesn't want you to be alive. I think the only thing that has done that for me is a community and the realization that I can go meet up with a bunch of other people and we can have a conversation, like the one we're having now, and it can involve some laughing and maybe some crying, and it can be totally fabulous. Our society not only wants us to be thin, but also doesn't want us to be friends with each other because if we're truly honest with each other, then we might realize that we don't want to be in this beauty competition because it's hurting so many people we love.

RFQ: Something I loved tonally about your book is it felt like it had so much explicit respect for sick and sad young women, which is really meaningful. So much writing is about us, but talks above us or around us or down to us or laughs at us or sneers at us or makes a fetish of us.

EC: We've definitely been condescended to, put on a pedestal only to be kicked off of it, and then once we're on the ground broken, they're like, “Why are you so bad at balancing?” We’re deeply pathologized and mocked and not listened to truly at all, in a way that, again, makes you feel crazy. I wanted to balance genuinely listening to you and understanding your voice as one with intellectual weight, while being conversational. Those types of tonal moves often get misconstrued as doing too much or not maintaining objectivity or all of these judgments that really come from patriarchal genre and literary standards. I was trying to really reject those. It felt like a risk because part of the political ethos of the book is that I want these diseases to be understood as the microcosms of social, economic, and political forces that they are.

RFQ: I think there's this element that if you really think about the universality of this pain that I have felt and every woman that I love has felt — if you really think about that, it kills you. It is a level that is politically urgent. The pain knocks you off your feet.

EC: It’s a completely crushing amount of pain, and then it's this sort of cathartic communal recognition of that pain that allows you to realize it can be politically mobilizing to feel the weight of that pain. It truly can't go on like this forever, and it makes me want to be alive in order to try to change it in what little ways I can so that maybe some younger girl doesn't have to feel this bad.

RFQ: There's this hopeful political urgency to it where you realize there's no moral option.

EC: There's no moral option other than trying to deconstruct this beauty standard. There's so many of us that if a critical mass of us decided to do it, we could do it easily.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.