Culture

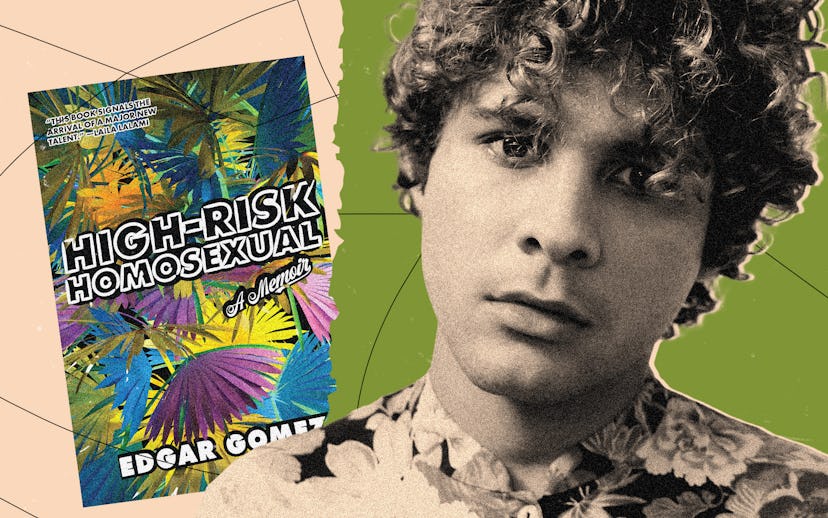

Inside Edgar Gomez’s Buoyant, Queer Coming Of Age Debut Memoir High Risk Homosexual

Gomez has a gift for taking in small, strange details as though they were rusty pennies on the ground for him to polish and shine.

Edgar Gomez didn’t know what book he was going to write. He just knew he wanted it to be gay.

One day while he was getting his MFA, he was sitting in a class and everyone went around the room and gave nuanced descriptions of their projects. “I was just like, ‘Gay!’” he tells NYLON, laughing. Eventually, one of his professors urged them to highlight one of the themes already present in their stories: how their queerness pushes up against the machismo embedded in the Latinx culture in which they grew up. Gomez realized this theme of machismo was already present in so many of the stories he wanted to tell, like when his uncle took him to a cockfighting ring or hired a sex worker so Gomez could lose his virginity. In a bigger way, it was present in the way they had a hard time expressing their emotions, like with their brother in the aftermath of the mass shooting at Pulse, which they describe in the book as “a different kind of home.”

Using the theme of machismo as a thread, Gomez creates a sometimes hilarious, sometimes dark, and ultimately very buoyant coming-of-age queer memoir in High-Risk Homosexual – and where their storytelling thrives most is in the strange, opaque moments between joy and darkness. High-Risk Homosexual is told in the bleakness of a bath house vending machine filled with Cup O’ Noodles, in the feeling of air in your lungs as you stand outside the club for a dance break with your friend, and in the gleeful absurdity of shaving a drag queen’s back as they take poppers to dull the pain. Gomez has a gift for taking in these small, strange details as though they were rusty pennies on the ground for him to polish and shine, slowing down the moments adjacent to life’s larger ones.

“I really, really do love to write about joy, but I always aim for the most nuanced motion or the most nuanced scenes. I think that’s my goal. A lot of these moments of joy are immediately followed by something horrible,” he says. “Queer people have so many weird, or not weird, but really specific experiences that aren’t necessarily captured often.”

Gomez spoke with NYLON ahead of his book’s release about his writing process, the lack of queer, Latinx memoirs being published right now, about how writing about the Pulse tragedy helped him grieve.

High-Risk Homosexual is out now on Soft Skull Press.

Tell me about the process of writing the book. When did you know you wanted to write it?

I didn’t know it was going to be this book until the last sentence. When I started writing, I was all over the place, not even necessarily in a bad way, I just didn’t know what kind of book I needed to write in order to sell a book. When I went into my MFA program, I was like, “I want to write a book about gay stories. I want it just to be gay.” There was one specific class where we were telling a professor our book idea and everybody had these beautiful, nuanced project descriptions and I was just like, “Gay!”

I think a reason for that was because a lot of the books I was reading at the time, at least the hugely successful blockbuster gay books, were David Sedaris and Augusten Burroughs and in their later works, there wasn’t necessarily, for me, a narrative thread; they were just collections. At least in that class, my professor was like, “No, you need to have an actual narrative thread.” I didn’t really know where to go from there. He was like, “You have machismo. That’s something unique to your story that only you can write about.” By that point, that professor had read a bunch of my stories, so I think they just saw something in them that I didn’t see at the time, so it went from “gay” to “gay and machismo.”

So it was the professor that pointed out the storyline of machismo or were you kind of aware of that before?

I think it was already present. I just didn’t know how to articulate it into the project that I was doing. My professor was basically like, “You are already doing this. When someone asks you what your book is, it isn’t just gay because there’s a bunch of books like that. Your book is doing something a little more unique to your experience.” I went back and read all the chapters and I was like, “Obviously this chapter about my uncle’s cockfighting ring and me being this really scared gay kid with machismo. Obviously this chapter about how you have a total inability to express your emotions has to do with the fact that that is a very machismo characteristic.”

Are there other works with work with being gay and machismo, or are you kind of one of the first to tackle both of these things?

I would say there are very few, but there definitely are. One big touchstone for me was Rigoberto González’ Butterfly Boy, and that deals a lot with machismo. It’s a memoir about coming of age in Riverside, California which is where I went to grad school, so there are lots of intersections there. But as a whole, the queer Latinx community is really underrepresented in the publishing industry. Another writer doing this is Marcos Gonsalez who just wrote Pedro's Theory, who blurbed my book. It’s not that there aren’t people that want to do that work, I just think there’s a lot of gatekeeping.

“Some of my moments of most intense joy are when I’m stoned with a friend and they say something that is so, so funny that you almost have a weird out of body experience and you get chills and you’re just sitting there so happy. It’s not this big melodramatic moment, it’s actually a lot quieter.”

One of the most beautiful things you capture is when you write about being out and dancing and nightlife and the community that’s fostered there. How do you go about writing something like a feeling like that that is so fleeting and intangible?

I think that the instinct of a lot of writers when they want to capture an emotion that is very, very meaningful to them is to go into melodrama. For example, if you’re writing about how badly something somebody told you hurt you, the instinct is to be like, “I was in such pain and it was so unbearable.” But I think, at least in my experience, pulling back and doing the opposite of melodrama and writing more cold captures that emotion a little bit better. For example, joy: Some of my moments of most intense joy are when I’m stoned with a friend and they say something that is so, so funny that you almost have a weird out of body experience and you get chills and you’re just sitting there so happy. It’s not this big melodramatic moment, it’s actually a lot quieter.

One moment in the book is where I try to do something like that is when I was in Riverside and it was the year of the Pulse nightclub shooting. I was very depressed and had PTSD and I’d gone to this gay bar called The Menagerie. I was just dancing with my friends and my way to try to capture that moment was I didn’t spend a lot of time in the club or describing the club, but my moment of joy was going outside for fresh air and standing next to my friend and feeling the breeze on my face.

Right, maybe that’s not the moment that someone would expect, but it’s the quiet moment you really appreciate.

It’s weird, that’s just what I remember more.

There are only so many ways to explain bodies brushing up against one another.

I feel like there’s some experiences that maybe better writers can capture very well. There’s just like a lot of experiences that if you’re not actually experiencing that — if you’re not dancing, if you’re not having sex — if you don’t think you can capture that, try to capture something else about that moment. The before or the after. If you can’t capture sex, maybe like the smoking a cigarette after.

I want to switch gears and talk about Pulse a little bit. How did you begin to be able to write about that?

That was really, really hard for a lot of reasons. Obviously, there was the emotional attachment to this place and to the people. There was also the idea of, “Oh my God, family members and friends of the people who were killed that night might read this and how do I navigate that and do them justice?” Then there were even technological difficulties. There are two chapters that really deal with Pulse. In one, I talk about the shooter and in one, I talk about the PTSD after. In the chapter where I talk about the shooter, I had to do a lot of research and just by merit of even typing his name into Google, the algorithm kept pulling him up and I remember at the time I was on Facebook and he was a recommended friend and I was like, “What the f*ck.” Sh*t you don’t even expect to confront. It was really hard all around, but honestly I just didn’t know how to not write about that.

A lot of times I would write about really traumatic things and memories that caught me in order to let them go. In my writing about Pulse, I was able to come to an understanding of how I felt about what happened and not move on, because I don’t really know what move on means, but not just be constantly consumed by PTSD and grief.

Totally. I’m sure that was healing in some ways, even if it was really difficult.

Yeah, in a really weird, twisted, warped way. I also just found it was nice to have something to focus all of my grief into as opposed to leaving it unchained and confronting me when I didn't want it to. At least it was like, for five hours today focus on this thing. When I finished, I was like, “Okay I don’t have to think about it as much.”

What have some of the reactions been from people in your life?

I’ll say the Pulse chapters, I was really, really nervous about them. So far, I've only gotten pretty good responses, but I think it’s because I worked really hard on them and I knew that it was a sensitive subject and that I was going to have to approach it with a lot of respect. Hopefully after the book is published, people feel the same way. The people in my book? In general, good. Nobody has said anything bad yet, but I haven’t necessarily told everybody that I write about that I’m writing about them, so we’ll see. I’m working on telling them but that’s a whole other thing.

You wrote about moments of joy so beautifully and vibrantly. What do you think is the most joyful moment in the book or your favorite moment of joy?

See that's complicated because I really, really do love to write about joy, but I always aim for the most nuanced motion or the most nuanced scenes. I think that’s my goal. A lot of these moments of joy are immediately followed by something horrible. For example, the day when I was talking about being in Riverside stepping out of the club for fresh air and just like how that was a moment of joy and then immediately the bouncer is like, “You can’t come back in here.” There’s a lot of contrasts.

Another moment that I think about a lot, it’s a scene that I haven't really seen a lot at least in literature, in memoir, specifically. But a scene that was fun to write was in chapter three “Mama’s Boy” where I’m shaving my friend who’s a drag queen. I’m shaving their back and we don’t have shaving cream and so they’re doing poppers I guess to make themselves feel better. That’s a scene that I think about a lot for some reason. Just a weird scene that in retrospect brings me joy. Growing up, I never saw stuff like that in literature. Queer people have so many weird, or not weird, but really specific experiences that aren’t necessarily captured often.

I think that’s why your scenes of joy stand out so much is because they are bookended by weird or nuanced moments.

Right, like literally in that scene, my friend has a boner and I love that that ends up being a big part of the story, that they secretly have a crush on me the whole time and I misinterpreted the friendship completely. That’s what I mean by stories being bookended by “and then something weird happened.”

Which is just, like, life.

Exactly.