Culture

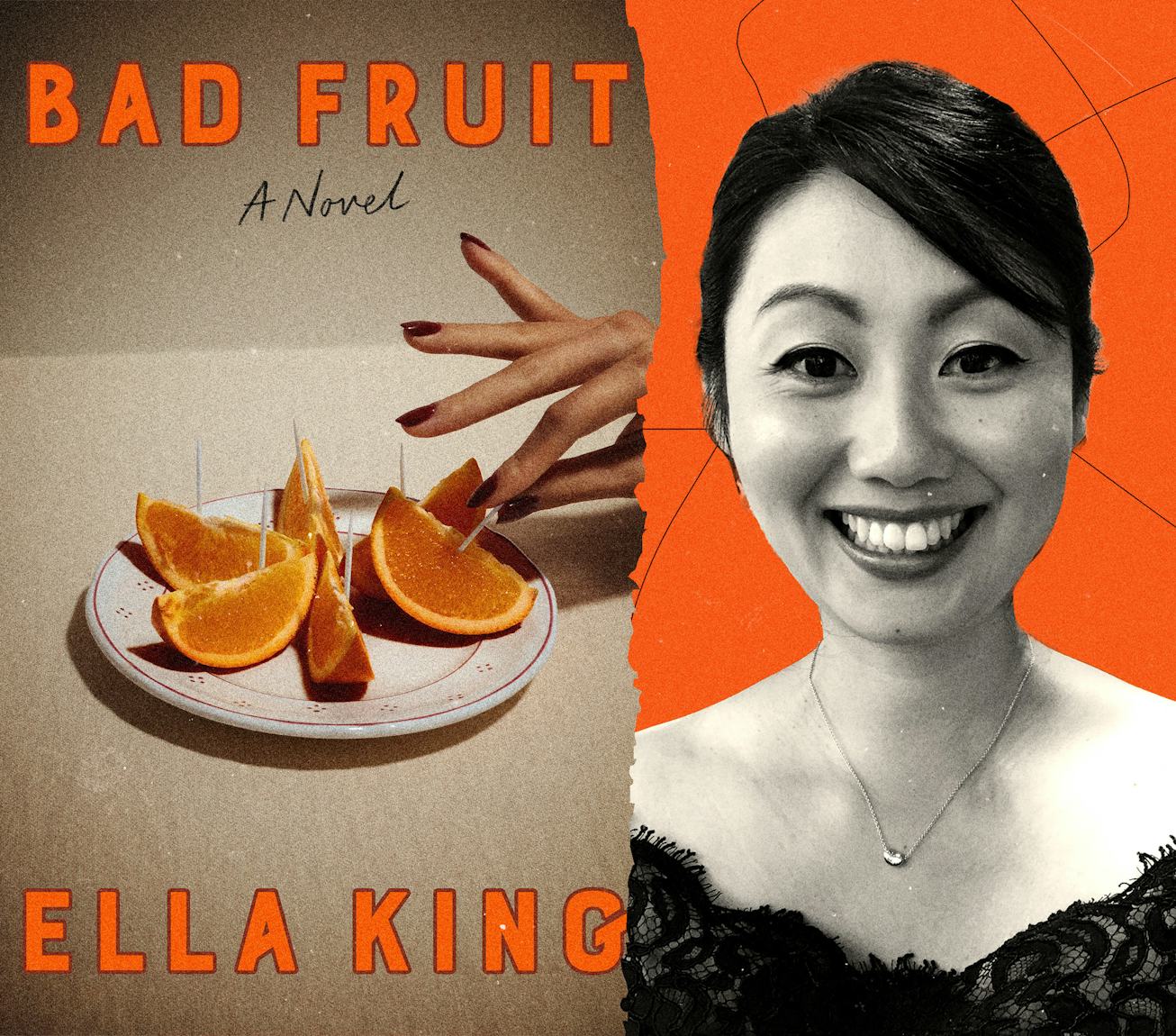

In Ella King’s Bad Fruit, A Mother-Daughter Relationship Is Extra Rotten

There's something wrong with the orange juice — and the mother-daughter relationship — in Ella King's debut novel Bad Fruit.

Ella King’s Bad Fruit is a claustrophobic, powder keg of a novel. A portrait of abuse, it hinges on absurdity and suspense to tell a wild story of familial trauma and reckoning that never feels like a “trauma novel.” 18-year-old Lily’s abusive mother May demands glasses of spoiled juice, an army of pristine teddy bears, and a closet full of solely pink clothes. With no help from her detached forensic doctor father and her incapable, wounded brother, it’s up to Lily to fill her increasingly difficult needs, as she tries to survive one final summer at home before starting attending Oxford in the fall.

“The kind of juice Mama likes is juice past its use-by date,” King writes. “She likes the fizz in it, the sour tang. I would have been fine with this if she kept it to herself. But Mama can’t be alone in anything, and with the juice, someone has to taste it to make sure it hovers in that sliver of perfection between expired and putrid. Each night, I stare into the plughole, my chrome oracle, and ask the same question – is it better to like expired juice or not?”

Over the years, May has turned Lily into her doll. Hell bent on having Lily look more Chinese than white, she forces her to dye her roots black and wear brown-colored contacts. Lily always does as is told, seeking comfort and affection in the form of a compulsive knowledge of linguistics and “accidentally” bumping into nice-looking men in London’s Greenwich Park to feel an ounce of touch. Her carefully constructed world goes haywire when she starts having flashbacks of her mother’s traumatic childhood in Singapore – leading her on a journey of reckoning she never wanted, but one that could set her free.

King’s South London is prone to eerie environmental extremes, both in and outside the home, with fights and rainstorms that are explosive and disquieting. Lily, in the aftermath, is always fixing something, whether it’s the members of her family or the destruction of trees in the Greenwich Park orchard.

King, a longtime attorney, always knew on some level she wanted to write a book about domestic violence, after hearing stories from her grandmother’s experience with abuse, as well as her pro-bono work with sex trafficking and domestic abuse victims. King first wrote an original version of the book a decade ago from Lily’s grandmother’s perspective, but scrapped it. She went back to the novel after she had her first daughter, and would spend hours thinking about it during the long hours she pushed her baby’s carriage around the park. When her baby would fall asleep, she would write on her phone. She eventually reworked it to be from the perspective of a present-day teenager, to make it feel more “cutting,” she says, and urgent.

“I'm interested in that victim perpetrator dynamic,” King tells NYLON. “How does that get switched up, and can it be switched up? When does the victim get the power?”

I want to talk about the tone of Bad Fruit. The abuse is pretty horrific and unrelenting, but there’s a unique absurdity to it as well, with details like the spoiled juice and the teddy bears. How did you make such a serious topic have a levity to it?

I think it's because the character May is just so extreme, and part of the manipulation is that her whole family is carried away by these elements. Lily, in particular, is the youngest child who is supposed to be on mother management duty. She is the one who has to placate all these weird urges that her mother has, so that's where the absurd element comes in. I've been thinking about how long I've been writing this book and when it started off, it was completely different. It was actually from the perspective of the grandmother figure who you hardly see, except for in the flashbacks. I wanted her to be in the UK and have flashbacks to her life, but I felt like that actually didn't have the kind of present pull that I wanted it to have. I had done a version of that and it never worked, so I had to scrap it and try something different. I tried it from the 21st century teenager perspective, so I think that that's also the other aspect of the voice that I wanted it to be quite cutting and quite present.

What was your initial vision for the novel? Where did the spark come from?

One of the key themes of the book is intergenerational trauma, so the idea that trauma can be inherited down family lines. I really started thinking about that a couple of years back when I visited this village in Cambodia with an anti-human trafficking charity, which is regarded as the epicenter of child sex trafficking in the world. I was literally looking through this window at a school room where 50% of the children were currently being trafficked. Their parents would literally take them out of school, drop them off at a Western man's hotel room, and then bring them back to school. And that was just what was happening. And I heard this quote, which really just really kind of shattered my understanding of abuse and intergenerational violence.

It’s a quote from one of the mothers who basically said: “If you love your daughter, sell her close, and if you don't love your daughter sell her far away.” Obviously the implication is that there's no question about whether to sell your daughter or not. It's just that the measure of love is determined by the distance that you sell her. I was really struck by that and I spoke to the charity about it, and their explanation for this quote was really clear. They said that basically this mother and all the parents who were doing this, were suffering from posttraumatic stress because they had been children during the Cambodian genocide in the 1970s. Their parents had been killed and they'd been forced to commit atrocities.

For them, trafficking their daughters was actually not a big deal compared to things that they had undergone. It was about the normalization of violence and abuse that was happening. I really wanted to bring that into the domestic sphere, because when I came back from Cambodia, I was then working with some survivors from a domestic violence center and seeing the same pattern happening. There's a slide from perpetrator to victim, and these parents who are abusing their children or abusing each other, have themselves been abused because the violence becomes normalized. I really wanted to look at that cause I felt like it had been really lost in media interpretations of domestic violence.

There's such a statistical link between things like mental illness and trauma, and yet we, we treat the depression, we treat the mental illness, and we don't try and really look at the trauma that's caused it, and it just seems to be kind a categorical mistake that we're perpetuating in society.

Is this the first time that your creative work has started to contend with domestic abuse?

This is my debut novel, so yeah. It's the first time I'm writing about it, but I think it was always going to be about that. My grandmother was a victim of domestic violence. Obviously, she didn't tell me about it until I was much older, but she kind of raised me and then as I grew older, she told me that these things had happened to her, and that was why she was in the UK, because when I was born, she'd come over to visit and she'd just never gone back. She'd just come with nothing. When she got a flat of her own, she was just so happy, because she never had anything. I was always really interested in domestic violence and what my grandmother had undergone and really trying to understand the kind of mentality and the psychology of survivors. My next novel is also, it's not about domestic violence, but it's also about trauma. I think it might be a trauma writer, I don’t know.

It's certainly a deep topic where there's so much to say. But even though Bad Fruit is about trauma, it's not a trauma novel. It doesn’t feel hard to get through. And it's interesting that it's been semi-marketed as a thriller. A lot of novels about trauma are heavy, and yours is heavy, but it also has a levity that carries the story.

I really wanted to be very deliberate about how I depicted the trauma. I didn’t want to be graphic. Even though these characters aren't real, I didn't want to be exploitative of either them or the reader's emotions. I wanted to tread lightly, because these things can be very triggering. I wanted to be really, really careful.

Lily’s devotion to her mother goes to an extreme level, with her colored contacts and hair dye. Those are such eerie details that sort of add to the thrilling, eerie element as well.

I think I was really deliberate about that because when I originally wrote the first couple of chapters, Lily wasn't multiracial; she was just Asian. And then obviously, because then I had a multiracial daughter, I started to realize how consistently, in a way that's different from the racism that I had experienced as just being Asian in the UK, that multiracial children and parents of multiracial children are consistently questioned about their parentage. My daughter used to have these big tantrums — my husband was dealing with her and we were meeting at a restaurant — and I was at the restaurant and could see what was going on. She's lying on the floor, kicking and screaming and he's trying to calm her down, and on the table next to me, these people start saying stuff like “My gosh, what's going on over there!” because my husband's white. They said, “Oh, he's not her father,” and they were going to call the police. They thought that he'd kidnapped her. I had to step in and be like, “No, I'm, I'm like the missing racial link.”

Episodes like that make me start thinking actually, what is it like for a parent to be consistently questioned about whether they are actually the mother or father of a child. I wanted to bring those elements in. Wanting to write a multiracial character was really important to me because I was actually thinking about it today, I can't even think of a multiracial protagonist in fiction. Actually, Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart. She's multiracial. But I think that overlay was really important for me.

Where did you get the inspiration for the spoiled juice? That's such a telling detail.

You know, I don't really remember. I know that it came very, very early. I had done this novel writing course, and at the end you read out a section of your work to a room full of literary agents, and that was the section that I read out. But frankly there were loads of bits like that, some of which aren't in the book. But that kind of came to me usually on a train or usually on the way to work. Those really cold November train rides on the way to work are very conducive to thinking about weird things, so it was probably on one of those journeys.

Were you working full-time while you wrote this?

When my daughter was born, she couldn't sleep unless I pushed her in the pram, so I'd be pushing her in the pram, like every day. I'd be going to Greenwich park and the Heath, which is where we live, pushing her in the pram and I would see the house, which is like Lewis's house. Lewis's house is real. I'd see it and think my gosh, wouldn't that be a great setting for something. I'd be spending a load of time in the park and then if she finally fell asleep, I would, you know, sit down on a bench and write on my phone. That's how it started, and that's why the landscape of the book is very much the landscape of my maternity leave. I'm a very slow writer. I'm a bit of a perfectionist, so it just takes me a long while to get it right.

And then I basically had this really weird bout with cancer in the middle. It was really weird and completely unexpected, and it was actually very curable. I was on chemo for seven months and I wanted to write, but I couldn't. I ended up sending out a lot of my work to competitions and things that I'd already done and I won them and then off the back of that, I got a lot of interest from literary agents. By the time that happened, I was kind of in the clear with the chemo and had got a great literary agent and then sold it.

We're on the brink of environmental collapse and in this book, there's so much extreme weather, which I feel like plays into the tension of it all. Did you want to intentionally create an environment that was extreme?

I definitely did. Apart from the fact that the weather has been insane in the past couple of years, just trying to thread some of that through, I think the idea of this rare and liminal space between the end of school, where Lily is faced with the prospect of having to make her own decisions and to wear her own clothes and what her appearance is gonna be. That's the question that she's confronted with. There’s a catastrophe that's happening in the family that really pushes the edges of her role, but also the climate that's happening, and the pressures that are put on her.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.