Culture

In Idlewild, James Frankie Thomas Captures Primal Teenage Joy

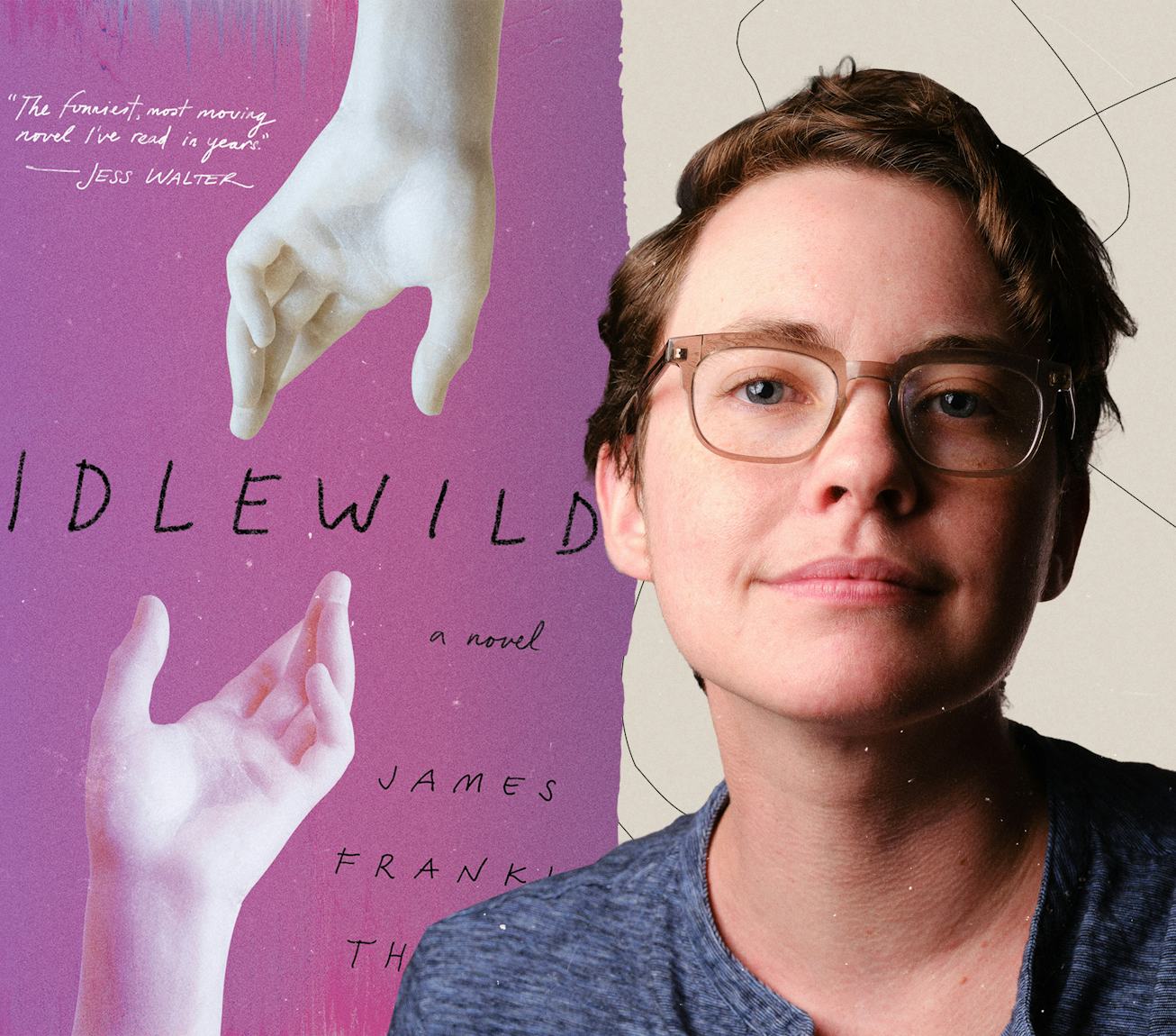

Inside James Frankie Thomas’ debut novel, Idlewild.

James Frankie Thomas is the kind of person who fills one with a sense of enthusiasm and possibility. It’s in the many exclamation points that punctuate his emails, the way he describes theater as his “one true love,” and his urging us all (here, in this interview!) to pursue the happiness that haunts us.

This sense of possibility permeates Thomas’s debut novel, Idlewild, and its teenage main characters, best friends Nell and Fay, who are overwhelmed with excitement about anything related to theater, homosexuality, and each other. “Something huge was blooming inside me, or maybe something huge was blooming in the world and I was just lucky enough to witness it,” Nell says, after seeing two boys from her artsy Manhattan prep school kiss. “Gay kissing, right here at Idlewild! I’d thought it was impossible – I don’t think I’d ever fully realized, until that moment, just how impossible it had always felt to me – and now, boom, it was happening. What else was possible now? Anything. Everything.”

With such heightened emotions, however, comes instability. Nell and Fay’s friendship begins on September 11, 2001, and unravels a little over a year later in betrayal. Thomas makes us voyeurs to it all, both through a precise, exuberant present-tense joint narration from Nell and Fay during their high school years, and in distinct, heartbreaking separate narrations from these characters, 15 years later. His puppeteer-like control of pacing guides us cinematically through scenes of euphoria, yearning, confusion, regret, grief, and hope.

Ahead of Idlewild’s release, Thomas spoke with NYLON about tricking himself into writing a trans novel, how narrowing his focus deepened the story he was trying to tell, being a Quaker school theater kid, and why we shouldn’t banish our high school ghosts.

The following contains spoilers for Idlewild.

When did you start writing Idlewild and what was your motivation behind writing it – personal, cultural, political, and otherwise?

In early 2017, when I was 30, I received a phone call from Lan Samantha Chang telling me I’d been accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Now, I keep running into this very common misconception (including on Girls) and I want to correct it on the record: You do not pay to go to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The Iowa Writers’ Workshop pays you to go there. This is to say that I suddenly found myself facing two years of zero responsibilities apart from writing whatever I wanted to write. As with any dream come true, the prospect was terrifying. I couldn’t waste this opportunity. What could I possibly write about that would keep me engaged for two years?

The answer came to me pretty quickly: high school. Specifically, my own experience as a theater kid at a highly permissive Quaker school in Manhattan in the aftermath of 9/11. The subject was rich with comic and dramatic potential, but I’d never written about it in any form, even though by 2017 I’d been writing professionally for a decade. I’d been avoiding it on purpose, but not for the reasons you’d expect. It wasn’t a site of trauma or pain. On the contrary: it was too happy. High school was a time of enormous, primal joy that embarrassed and saddened me to remember – embarrassing for its intensity, sad because I’d never felt it again. I made a lot of jokes about how I “peaked in high school,” like a washed-up star quarterback. Like so many of my jokes, it wasn’t a joke at all. Yes, I thought, I could spend two years exploring that.

I ended up spending five years on it. The problem was that my actual high school experience wasn’t eventful enough to be a novel in itself, so I had to make up a story with fictional characters, relationships, and events. (When I insist that Idlewild is completely fictional, I do so in a spirit of pride, not ass-covering, because I worked hard on that made-up story.) But what fueled me throughout those five years was that enormous, primal joy – the memory of it, the mystery of it, the possibility of touching it again.

Idlewild is told from three perspectives: teenage Fay and Nell together (“the F&N unit,” as they call themselves), and each of them 15 years later. When did you discover you wanted to bring these perspectives into this story and what do you feel it adds?

Surprisingly, the form preceded the function. From the very beginning, when I was first conceiving the novel, I knew I wanted it to have these three narrative modes. Back then, in 2020, I envisioned a novel more sweeping in scope, full of social and political commentary. The idea was to contrast an exuberant, bloggy 2002 voice with the more tempered, mature prose style of the older characters, to illustrate how Times Have Changed.

But this structure also came with the built-in implication that Fay and Nell had once been so close that they essentially shared a brain – and then, at some point, they’d ruptured. And believe it or not, when I started writing, I didn’t know why they’d ruptured. I vaguely knew it had something to do with a boy named Theo Severyn, but I hadn’t worked out what, or how, or even when. I hoped I’d figure it out as I went along. But when I workshopped an unfinished first draft in my second semester at Iowa, it was clear from the feedback that this approach wasn’t working. The earliest draft had a scene of Fay and Nell hanging out together in their twenties, and I remember my brilliant classmate Anna Polonyi asking, “If they were still friends in their twenties, why is the novel primarily set during their senior year of high school?” Good question.

It was Lan Samantha Chang, my thesis advisor, who gave me the single most useful note I received on that cluttered early version of the manuscript: “There’s a lot going on here, but what’s making me turn the pages is the friendship between Fay and Nell. I want to know what happened between them.” Duh! And so I began a new draft with a compressed timeline and a laser focus on the friendship. It’s amazing how a narrowed focus and a smaller canvas made everything so much richer and deeper, bringing me to bigger insights than I could achieve by trying to do broad social commentary.

You don’t shy away from showing the complicated, painful, even ugly parts of discovering and embodying queerness. Why was it important for you to look at the whole picture and was it ever challenging to determine how far to go?

In a way, I was incredibly lucky that I didn’t know I was trans when I started writing Idlewild. I had no idea I was writing a novel about The Trans Experience, which completely freed me from any inhibitions I otherwise would have had about such a fraught undertaking. I think this blissful self-ignorance is also the magic ingredient in my surprisingly popular short story “The Showrunner,” which I wrote when I was 23.

For the first couple of drafts, my goal was simply to recapture my high school self with perfect accuracy. I was determined to avoid clichés. Instead, I would lay bare the reality of teen girlhood in the early ‘00s – like how we were obsessed with gay men and gay culture, and how we were helplessly aroused by the thought of two men together, and how whenever we liked a boy we hoped he was gay even though that desire made no sense, and how after high school we could no longer get away with talking about that kind of thing in public, and how ever since then we’d gone around feeling like some part of us is gone and we’d never again be as fully alive as we were in high school.

By the time it finally dawned on me what kind of novel I was actually writing, and what this novel was saying about me – not about teen girls in general, but specifically me – it was too late to turn back. I’d tricked myself into writing a trans book. If it sometimes presents gay transmasculinity in an unflattering light, that’s because I was too dumb to know I was doing trans representation at all. Of course I figured it out eventually, but by then the novel had enough of a life of its own that I was concerned only with making it work on its own terms. I really dodged a psychological bullet there.

After reading the epilogue, I feel like in many ways, Nell gets a happier ending than Fay. They’re both still deeply connected to the high schoolers they once were, but Fay wasn’t able to come to terms with her transness at 33 (or maybe she’s on the verge of it and we just don’t get to see it). Is this also your reading of how their stories end and what does it mean to you to leave Fay in this emotional space?

That ending is proving to be a real Rorschach test, more so than I ever expected. Some readers think it’s unbearably bleak. Others, especially trans people, read Fay’s ending as gorgeously hopeful. One fascinating Goodreads review (yes, I look at my Goodreads reviews, sue me) made a case for Nell’s ending being worse than Fay’s: “reading Fay's ending was unbearable but it might be Nell's that will haunt me – better off than Fay financially, physically, socially, more comfortable in her queerness than Fay is in his [sic], and yet – the blame, the mercilessness, the sublimated rage, neither the kneejerk generosity nor the lightheartedness that comes with temporal distance quite managing to cover the complete absence of compassion for herself or others.”

All these interpretations are valid, but since you asked, here’s my own take: Fay and Nell are only 33! Being 33 is not the end. For many of us, it’s just the beginning. Like all 33-year-olds, both Nell and Fay have problems they’re going to be dealing with for a very long time. Nell has a fulfilling career and a meaningful friendship, but in many other ways she’s quite stuck in her life and adrift in the world, more so than she’ll admit to herself. Fay is, as you say, “on the verge” of something major; she’s in a lot of pain, but any transsexual will recognize that pain as the prelude to a breakthrough – and the final page of her epilogue as that breakthrough. The novel ends at a certain point in their lives, but their stories are not over.

Theater plays a huge role in Fay and Nell’s lives and friendships. From one theater nerd to another, what is your relationship to this art and how does it show up in your writing?

If you Google me, one of the first results is a link that says “‘My true gender is theater kid’: the James Frankie Thomas story.” It’s a link to my episode of the Teen People Podcast. I find that headline a little embarrassing now, not because it’s embarrassing to be a theater kid, but because I did that interview on September 12, 2021, which was the day before my long-delayed, much-anticipated first dose of testosterone. I was secretly a basket case, and I think it came across a little. “My true gender is theater kid” now strikes me as such a funny one-foot-out-of-the-closet thing to say, like the modern equivalent of calling yourself a confirmed bachelor. Just say you’re a gay guy!

But theater really is my one true love. I used to review shows for Vulture and hope to do it again one day, but I actually prefer amateur theater to professional theater. I’ve been known to attend school plays without knowing a single kid in the cast. School plays are so high-stakes! When I was in the ninth grade I attended my school’s fall play, The Winter’s Tale, and the senior boy playing King Leontes actually cried onstage! It was the bravest, most powerful thing I’d ever seen in my life; I went back to the second performance just so I could watch him do it again. I vowed on the spot to audition for the spring musical – which happened to be On the Town.

That’s the major reason On the Town plays such an important role in Idlewild. As a ninth grader, I was relegated to the ensemble, but that’s the best way to learn a musical by heart, so I have every note of the score memorized. It’s a really underrated show: the music is beautiful, and the book’s absurdist, horny sense of humor has aged remarkably well. (“I Understand” is a character song about a chronically cucked man who’s so conflict-averse he once let a guy run over him with a car.) Plus, it was life-alteringly exciting to spend every afternoon in the presence of King Leontes and the other cool talented upperclassmen. One night I got home from rehearsal and started crying uncontrollably because I was so overwhelmed with joy and adrenaline and nonspecific yearning. That was a feeling I wanted to capture in Idlewild, and On the Town was my entry point to it.

What art have you engaged with – literary, visual, musical, etc. – that influenced or supported the writing of this novel?

I was an English major at City College from 2014 to 2016, and the curriculum there was heavy on British modernism. Writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, as taught by my professors Václav Paris and Robert Higney, really got me thinking about the possibilities of form and the infinite ways you can creatively shape it to fit the material. If it weren’t for them, I would never have considered something as ambitious as a sustained “we” voice, but thanks to my modernism studies it came to me right away as the natural form for this story.

During this same period, there was a literary trend for fiction written in long retrospective first person. Between studying Ulysses and Mrs Dalloway, I was of course devouring Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, and I also became quite obsessed with Alejandro Zambra’s story “Reading Comprehension: Text #1.” At the time, I found memoir easier to write than fiction – I still do – but Ferrante and Zambra led me to an epiphany that the long retrospective voice offers all the pleasures of memoir with the added delight of total imaginative freedom. They’re the reason Idlewild’s “we” voice alternates with Fay and Nell narrating from fifteen years later, with all the cringing regret, imperfections of memory, and belated compassion that comes from a distant perspective.

Once I got to Iowa and lived alone and my job was just “book,” I gave myself permission to embrace gay fanfiction like I’d never embraced it before. Telling myself it was important research, I spent pretty much every free second of my life reading gay fanfic, and for the first time in my life I even wrote some fanfic of my own. I’m not sure how much of this “research” actually informed Idlewild, but I made some great friends in my fandom and we’re all gay men now, so that was an important part of my personal process, if not my writing process.

In Idlewild’s epilogue, adult Nell says, “I regret who I was back then. At the same time, I don’t know if I’ll ever be happy in that same way again. And I don’t know what to do with that.” Do you think our high school ghosts have a useful or meaningful place in our adult lives? Can we ever get rid of them and should we even try?

I could treat this as a craft question, a trans question, or a general existential question, but my answer is the same in any case: if that kind of happiness is haunting you, pay attention to it. Pursue the happiness that obsesses you. Even if it’s an embarrassing kind of happiness, even if you don’t know why you’re obsessed with it, even if you wish you weren’t – it’s going to haunt you no matter what, so you might as well follow it and see where it leads you.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on