Culture

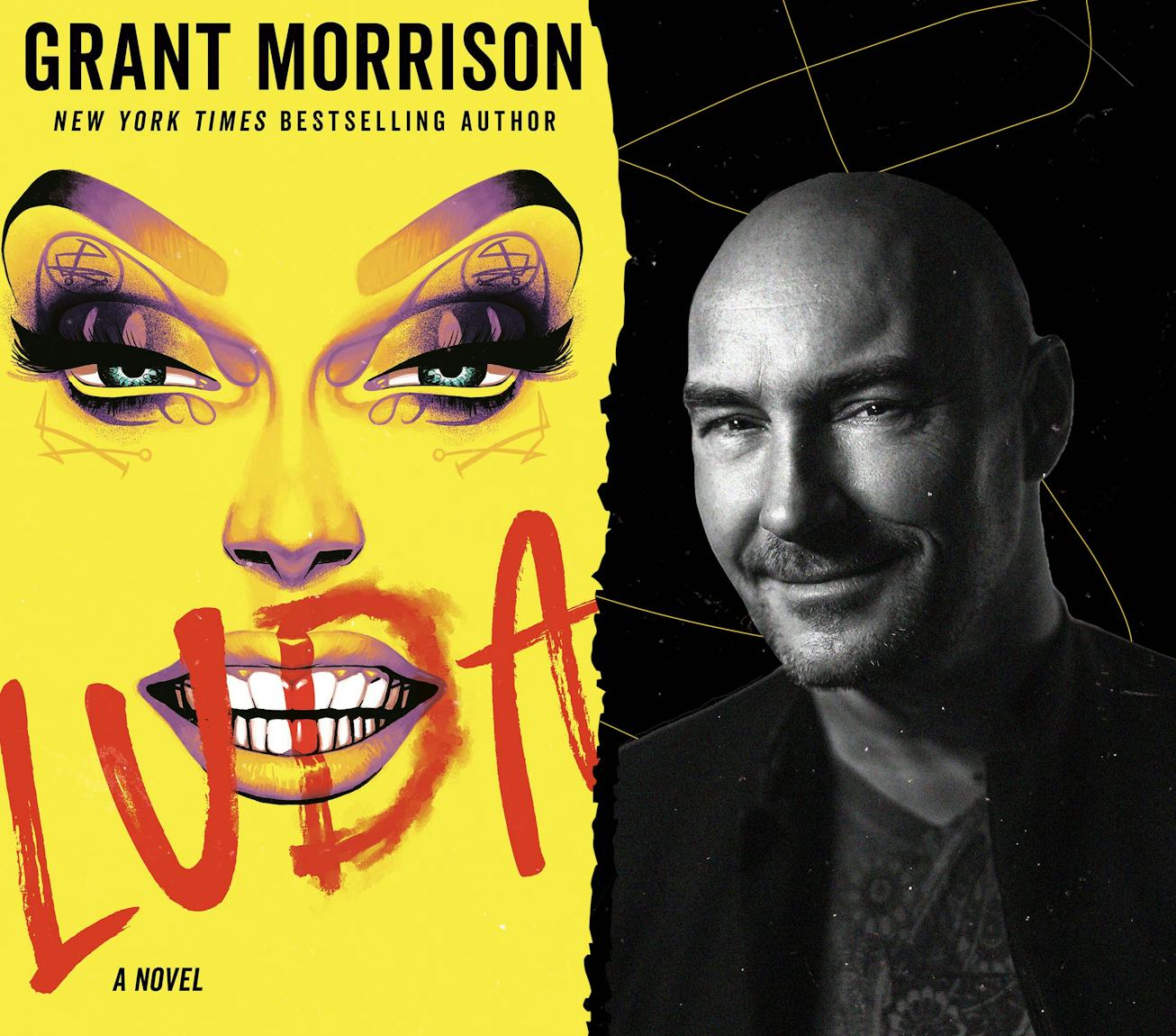

With Luda, Grant Morrison Weaves A Drag Showdown

Grant Morrison speaks on their debut novel Luda, an evocative hall of mirrors filled with drag queens.

“I’ve always aspired to be what’s left when the Invisible Man relaxes, takes off his fedora and his Ray-Bans before unwinding … into a discarded bog roll bundle on the lino.” So confesses Luci LeBang, the titanic arch-vamp whose monologue makes up Grant Morrison’s new novel, Luda. Luci is an old-school showgirl, and we are her green room guests before she hits the stage. As she narrates her neon-lurid tale of a cursed pantomime production, a drag grifter and a shadow conspiracy underneath the mystical city of Gasglow, she layers her face. Everything is external. And yet, for a grand dame built on exteriority, all she longs for is the void beneath the bandages, “that unfettered absence, that unlimited potential … when you unzip the dresses, unbuckle the heels and roll off the stockings, you’ll find there was never anything else. There was only drag.”

Perhaps there is no Luci LeBang. And perhaps there is no Grant Morrison. Though this is the author’s first foray into prose fiction, they are the unrivaled rock star of the comic book medium. Since storming comics in the ’80s as part of the U.K. talent takeover, along with such luminaries as Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore, they have since steered the lowbrow mythology of our age into a new millennium. Writing themself into their comics, as in Animal Man and their opus The Invisibles, Morrison has crafted an abundant public persona. They are beloved, among other things, as a pop chaos magician, musician, psychedelic spelunker, and gender experimentalist.

And yet, Morrison, like Luci, understands these aspects of self to be adornment: no less valuable, but not necessarily intrinsic. “I know there are some of us,” they tell NYLON, “where inside there’s an emptiness, whether it’s a Buddhist kind of emptiness or just a pure zero.” This is no nihilistic Patrick Bateman confession but an unshackling from the burdens of identity. “I don’t feel attached to any gender,” they say. “I don’t feel attached to my nationality. I don’t feel attached to my species, to be honest.”

Morrison describes this inherent self-neutrality as a “superposition, the idea of having multiple potentials existing simultaneously,” a gate to endless personalities and possibilities within, which can best be channeled through the mercurial art of drag, and in the ensemble dramas of comic books. With the rise in popularity of psychiatric theorist Richard Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems, which posits each person as the host of multiple inner parts, all with their own desires, needs, and trauma responses, our internal universe may be shifting from me to we. “There’s a swarm of versions of me,” Morrison says. “Some are boys and some are girls; some are tough; some are weak. I don’t see it as a kind of dissociative disorder: These characters all sit around a table and work together.” The deadly femmes of their New X-Men, the glorious constables of their Justice League of America, and the punk terrorists of The Invisibles, then, are all facets of Morrison.

Luci, at first, may come off as the writer’s most outrageous avatar yet. Morrison conceived of the project for audiobook format, so “the language has to be pretty evocative — over the top. If people are sitting and listening to it, and driving to it, you want to make it cool to listen to, almost like pop music lyrics.” Every sentence is a dare, more outrageous and decadent than the last. No matter how deep into the basement of lunacy the plot descends, Luci maintains her droll, delicious narration, sipping Veuve Clicquot and serving asides in the acerbic tradition of Terrence Stamp — and Crystal LaBeija.

And yet, for all her world-weariness, Luci is a joyful creation. Morrison, ever the optimistic Aquarian, has resisted the aggro vogue of “dark” and “gritty” postmodernism in their comic books; they understand that it’s braver to depict Superman saving the day with a smile than glowering in the rain. However vicious her barbs are, Luci is eager to open her heart and share her hard-earned wisdom. “I think she lets you in so deeply to what she’s been through that we can find some empathy there. As you grow older and accumulate experience, as you have the sh*t literally kicked out of you by life, hopefully you’ll develop a more empathic way of viewing things.” She gets her chance to connect, and pass on knowledge, when a stray queen called Luda turns up asking for help.

The young Luda is an enigma, a facetuned shell of youthful perfection, a scheming drag mastermind who can shapeshift to fit the desire of the beholder. As the relationship deepens and Luda’s bizarre origins are exposed, Luci finds herself in a hall of mirrors, distorting every feature until there’s nothing left. “One of the primary roots of the book was the story of the wizard Merlin and the young witch Nimue. It was that great story, which is basically the same as All About Eve, or A Star Is Born, where there’s the older, brilliant practitioner, who takes on a young pretender,” says Morrison. “They’re flattered by their attention; they can’t believe that someone young and beautiful wants to be with them. Ultimately, Nimue is trying to steal Merlin’s power, and then she imprisons him in an oak tree. I was thinking of that notion of the master and the pupil and how it can so obviously go wrong.”

The ensuing showdown, between drag artist and con artist, distorts any paradigm of gender and genre, rendering both combatants at once ingenious, moronic, savage, and ultimately sublime. Like Morrison’s own liquid relationship with their gender identity, Luda is too versatile, too self-aware, too kinetic, and possibly too fun to be lumped into any roundup of “important” trans or queer literature. But, if such a thing as drag literature exists, the sort of books that Divine is reading in heaven, Luda belongs at the top of the heap. “I like being witty,” Morrison says. “I grew up with Oscar Wildes and Quentin Crisps; I loved the wit of gay men, and I brought that to my life. Just being allowed to talk with that version of that voice, to elaborate that, and make it more baroque and psychedelic, was great.”

Beyond Luda, Morrison processes personal history through their Substack Xanaduum, an evolving, possibly sentient archive of collages, annotations, forums, and ideas. The pieces, Morrison insists, fit together into a larger evolving story; this isn’t a rehashing of old memories. “I have very little interest in the past, unless I can use it in some way. Like Luci says in the book: I don’t want to be young now; I want to be young then. What I didn’t want to do was a museum. The idea was to bring the archive to life, which is why there’s a framing science fiction story around it, about drawings going into the ruins of the Internet, and trying to reconstruct human personalities from fragments. I think that all that’s left of human lives: fragments.”

Morrison’s great epics, from New X-Men to Action Comics, culminate in a new union of those broken fragments, kabbalistic climaxes of collective oneness in which whole universes restart from the pooled imaginations of the many. Morrison, and Luci, done with the tired idea of individuality, are ready to cast their wisdom into the collective stream, and contribute to the budding one mind. Perhaps Luci’s bespoke cocktail of magic, known as The Glamour, is one door to the mothership, a future unbound by imposed division, “that moment, the enlightenment, the singularity,” Morrison says, speculating on the inevitability of mind-linking networking technology. “All that takes is for enough people to link up and say, ‘Sh*t, we’re all one thing.’ What happens when you’re faced with the prospect of becoming part of a giant omni-consciousness? Do you join? Do you stand aside? You’re now a T-cell. That’s the best you can be.” Luda affirms that our stories have meaning, but that our identities are no more than roles in a pantomime. As Luci says: There was only drag.