Culture

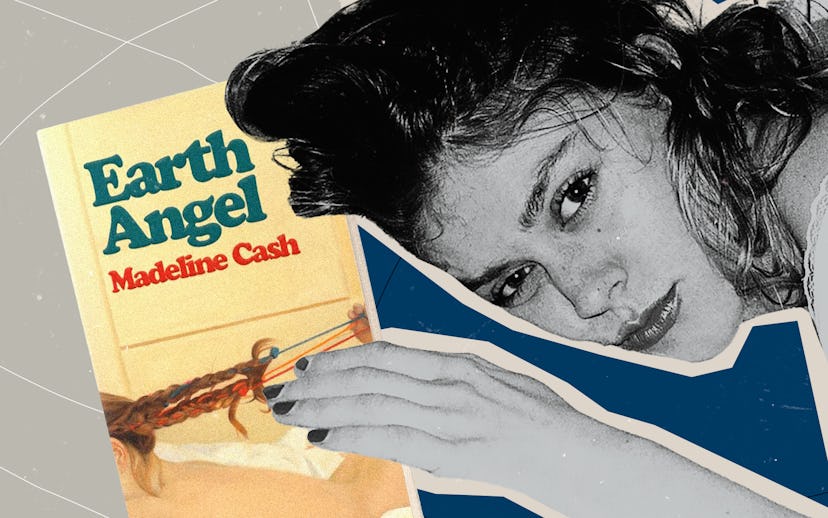

Madeline Cash’s Earth Angel Is Wide-Eyed Amidst The Decay

The debut short story collection reads like one long drag on an impossibly addictive candy-flavored vape.

Madeline Cash thinks a lot about the things you’re not supposed to say.

“What I've been thinking about a lot lately is what you're supposed to write about and why, and taboos and why they're taboos, and if I’m allowed to cross lines a little bit and see how it goes,” the writer and Forever Magazine editor in chief tells NYLON, while sipping on an orange wine at Golden Diner in the Lower East Side on an April evening. It’s been sunny all day but our Weather apps tell us a downpour is imminent. We plan our outfits accordingly. For her, this includes a single cross necklace. “Anything that you learn about creative writing, I want to see if I can simplify it a little bit: Tell you everything that everyone is thinking or have people think things you're not supposed to think.”

In Earth Angel, Cash’s fever dream debut short story collection, her characters would rather eat Tide Pods and think Osama Bin Laden is gay than break up with their reality TV star boyfriends. They mine Bitcoin at sleepovers; play “Marry F*ck Kill: The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” and are “perennially updating like a smartphone.” Earth Angel is a book about technology and girlhood in a time when things were grim enough to know that the future was going to be more grim – capturing an era experienced most strongly by cusp of Gen Z and young Millennials who grew up without cell phones, but who know about fax machines, away messages, and Bitcoin.

Sure, some of what’s in the book, out of context and in some circles, could get you into trouble. But that’s because Cash grew up in the mid-aughts, during a time when anyone had unfettered access to ISIS beheading videos on YouTube. Earth Angel is a bible for those of us who came of age in the wasteland of 2007 to 2010, for children of the internet who starved their Neopets and who questioned not if they’d get a letter from Hogwarts one day, but if they’d be recruited to join a terrorist organization.

“It was such a wasteland,” Cash says. “But not enough that people who actually fought through actual wars respect us at all. It really is this insular era that will get forgotten if not documented.”

“Hostage #4” along with “Plagues,” which details the end of the world where, “In God’s absence we pierced our ears and sullied the purity of our flesh and and bought crypto and wrote auto fiction,” are written in Cash’s signature style, which she describes as “imitating a computer imitating a person, just spitting out crazy juxtapositions of sentences.” No words are wasted in Cash’s stories, which read like you’re microdosing a glimmering lucid dream in 128-bit color.

Cash began writing “Hostage #4,” in a Google doc that would become Earth Angel when she was 23 years old and living in the San Fernando Valley with her mom after graduating from Sarah Lawrence College. As she began publishing short stories in publications like The Baffler, Hobart Pulp, and The Literary Review, she started noticing throughlines and characters that repeated, “probably just because they repeated in my life,” she says. It’s not a coincidence, for instance, that a lot of the characters have single moms, which Cash also has. (Her mother is a hospice nurse for a convent, which means “she’s definitely going to heaven.”)

Earth Angel became a book in and of itself about a year ago. Now that the stories are collected, Cash is faced with having to talk about what her book as a whole is about – a question she and the book actively resist.

“I've just been making up fake quotes,” Cash says, explaining a recent job interview where she was asked about it. “I was like, ‘People are saying that it's a critique of dot com liberalism, or it's about the virtual class, or it's how the path of the future leads you to the past and things like that. But no one actually said that. I guess the book's about that, but I just don't want to say that.”

But instead of extrapolating in real life or on the page, Cash gives her characters tiny bombs of dialogue and desire to cradle and detonate; what’s beautiful is watching it all explode.

“The book is really stubborn to me,” Cash says. “I wanted to not give anyone anything. There are all these rules you learn in writing school and I was like, ‘What if I just break all of them, and see if I can still get a book published?’ It's an inside joke with myself.”

Cash understands we’re in a time when fiction has to compete with the maniacal dopamine-driven algorithms of tech overlords. She is a master of economy when it comes to prose; some stories read like one long drag on an impossibly addictive candy-flavored vape. It’s almost as if she doesn't have time to explain anything to us. That’s not because she can’t (“Jester’s Privilege” in particular is written in what some would call a more traditional prose style, where Cash’s voice remains as sharp as a direct-to-consumer razor) but because, I'm not sure if you’ve heard, but it’s looking like the world is going to end.

“There are all these rules you learn in writing school and I was like, ‘What if I just break all of them, and see if I can still get a book published?’”

One of these greater looming forces that Cash doesn’t have to come out and say but is as persistent as the nitrogen dioxide haze of Los Angeles, is climate change. She doesn’t mention the term once, but there are endless examples of weather events leading to the end of the world: In “Fortune Teller,” bees commit mass suicide, a daughter “joins a satanic cult and starts a countercultural podcast and marries a man like her father,” and “Hollywood Boulevard is a third world country.” It’s not something you have to come out and say when you were born in 1996, two years after the 1994 LA earthquake that broke all of Cash’s mom’s wedding gifts and when, at least for those of us who grew up on the West Coast of the United States, you’re a pro at earthquake drills before you are even literate.

“It's not even in a way that is political or has a slant or that I'm being an activist. It's just genuinely growing up with this fear,” Cash says. “When we were little, that was what people were most concerned about with the world ending: In LA, an earthquake was the big one.”

In Earth Angel, there's always something sinister happening alongside what is childlike and girlish. While technology is not always menacing (have you ever visited the website Dollzmania?), in the mid-aughts, less than a decade from 9/11 and in the throes of an economic crisis, everything felt a little ominous. Homes were foreclosed on; the viruses from PornHub and Limewire infected computers. In “Earth Angel,” a girl named Anika (also the name of Cash’s BFF and co-Forever editor) hands an evil CEO a handwritten letter on Hello Kitty stationary. In “Slumber Party,” the itinerary for the sleepover includes “1am: Mine Bitcoin and build blockchain” and “4am: Networking,” in “Autofiction”, a girl has a long beautiful ponytail and a Japanese man tricks her into cutting it off, and in “Hostage #4,” a girl tries to trim her pubes and instead cuts her labia, ending up in urgent care. Girlishness is always getting intercepted by greater forces.

“When you're boiled by the internet, then it's sort of just you're your own enemy or you're boiling yourself, which I feel like was what it is to be a young girl,” Cash says. “You're constantly shooting yourself in the foot.”

But in the end, girls always prevail; they can see everything the clearest. While Earth Angel offers a taste of societal collapse like a spoonful of caviar from the Suez canal, the book is not nihilistic: It’s life-affirming. In fact, it’s quite sweet. There are sleepovers, there are pleated skirts; there are younger siblings, and there are always friends. Yes, the future leads you to the past and vice versa, and the last page of the book contains a grainy photo of a black hole – but ultimately, life, both physical and digital, is pretty absurd and to be able to capture it at all, makes it all more bearable.

We order another glass of wine and Cash brings up a quote from the media theorist Marshall McLuhan, about how “when you're using a tool, it's really just an extension of yourself. You're using a hammer to help you better be an extension of your arm,” she says, which makes her wonder, “When you're using a computer, what part of you is that an extension of?”

For Cash, I think about how writing is an extension of her brain, a self-aware one that can acknowledge the pleasures and pitfalls of the zeitgeist without getting swept up in any of it; a brain that humbly understands that on the brink of societal collapse, if we’re all going to Hell anyway (unless your Cash’s mom), we might as well just have a little fun and be nice to each other. The Earth Angel book party did not include a reading; it’s not that serious. Cash’s alt-lit magazine Forever similarly shirks rules because so many things matter more than rules. Recently, Cash was surprised to receive fan email from a Harvard student.

“I’m like, girl, you go to Harvard, you're so much smarter than me. I should be a fan of yours. I'm going to be working for you,” Cash says. “You're going to be making jet engines. I'm going to be writing auto fiction.”

In a debut collection, particularly one that is auto fiction, people have a tendency to extrapolate personal meaning from the work. Cash has been asked more than once if the painting on the jacket cover is her. (It is not. It is a painting by the artist Shannon Cartier Lucy.) To be clear, Earth Angel is a work of fiction. But what’s more interesting than gleaning insight about Cash’s political beliefs or whatever, is considering who she is right now, and everything that she wants to say, and whether a debut collection of stories written across three life-changing years represents who she is now, as someone who is constantly rebooting.

“To be totally honest with you, I'm 26 – it sounds really trite and like an after school special, but I don't know who I am fully,” Cash says. “It's so hard for me to form my own identity, for lack of better words. I'm a copywriter, so my job is to chameleon into other voices. Even before that, I feel like my whole identity in high school and college was molding to whatever personality I needed to be in at the time: being an activist, being anorexic, being a baby doll. It was like whatever at the time was appropriate, I could kind of lend myself to. Now, I feel a bit of freedom from that for the first time in my life.”