Culture

Marianne Eloise’s Uniquely Obsessive Inner World

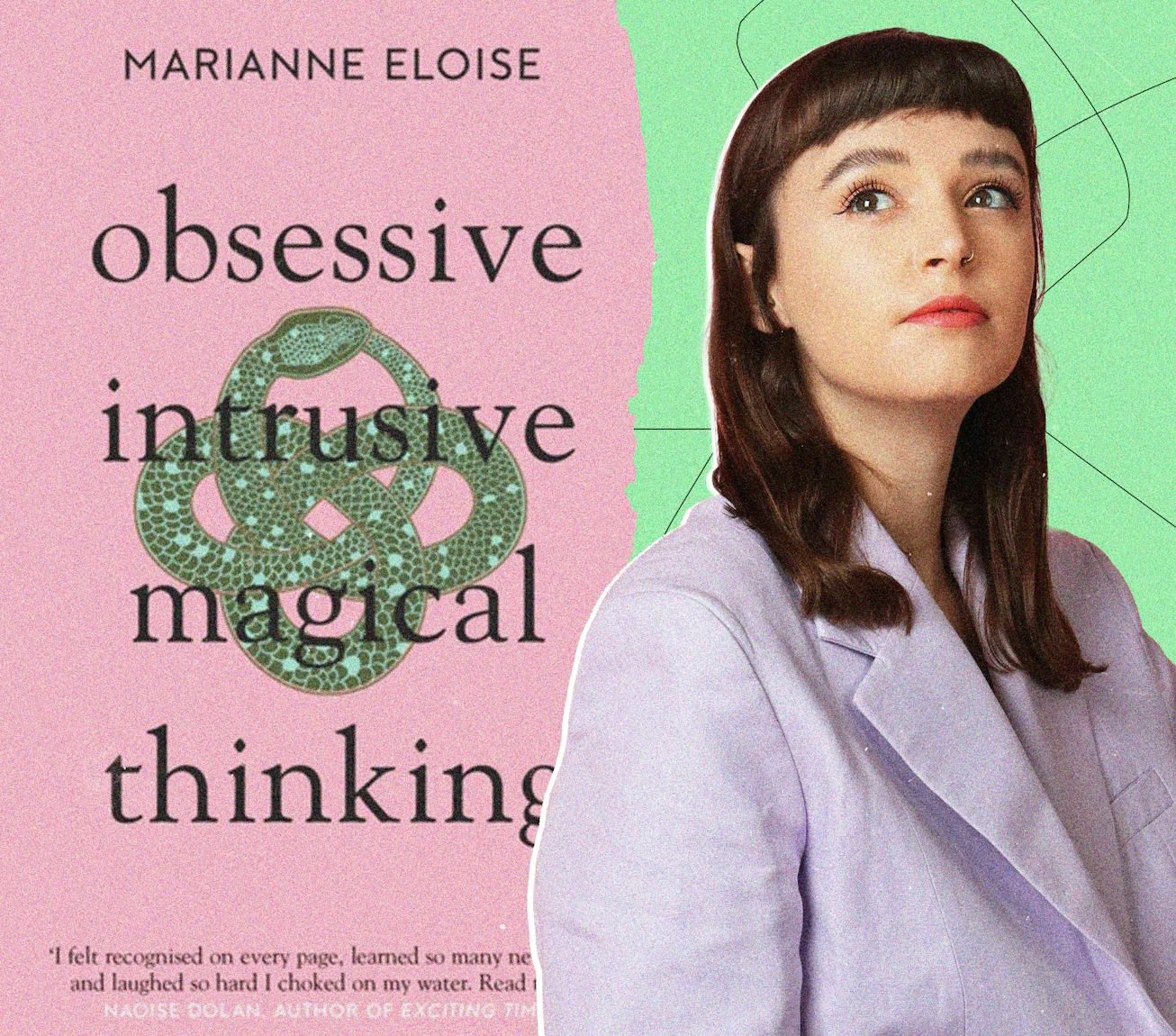

In her debut book Obsessive Intrusive Magical Thinking, Marianne Eloise’s brings her "uniquely obsessive" inner world to light.

The first thing to know about writer Marianne Eloise’s debut, Obsessive Intrusive Magical Thinking, is that it’s not a self-help book. She didn’t anticipate having to specify that, but the collection of essays about obsessions through the eyes of an autistic woman with OCD and ADHD, has mistakenly been interpreted as a guide to living your best, neurodivergent life. While Eloise wishes she had all the answers, “I can’t even help myself,” she laughs nervously. But she’s trying.

In Obsessive Intrusive Magical Thinking, out July 19 in the U.S., Eloise deep dives into her obsessions across lyrical, often funny, prose. In three sections (obsessive, intrusive, and magical thinking), the essays are segmented by their subject matter and tone, oscillating from dark to light and back again. While some of the subjects of her obsessions may keep her up at night — the possibility of a house fire, her dog’s impending passing, Medusa — Eloise’s writing is consistent in her strong sense of belief, whether it’s in folklore, magic, or the pursuit of a peaceful life. Sprinkled with references to The O.C., Fall Out Boy, Greek mythology, and Joan Didion, the essays will leave readers feeling secondhand joy and maybe even encouragement to own their love for their own less-than-cool favorite things.

Through investigating her wormholes and intrusive thoughts Eloise sheds light on how she uniquely experiences the world. “Being autistic underpins literally everything about me, what I eat, where I go, who I’m friends with, what I’m interested in, what’s hard for me,” Eloise explains, “My biggest thing was that I wanted to get across in the book was that I have this brain, and because I’m autistic, this is how I view the world. Here are the good things about it.” She doesn’t speak on behalf of autistic folks everywhere, but hopes that telling her story through the lens of pop culture may help readers see autism differently. “Maybe if they had their own prejudices about what it meant to be autistic, maybe, it would help them to realize their assumptions weren’t right,” she says. “I am one person and we are all extremely different. When I talk to my friends who are also autistic, we have such different interests and needs. What’s helpful to one person is hell for me, which is why I never wanted to veer into self-help.”

Born in Leicester, a dreary city in the middle of England, Eloise now lives with her dog and fiancé in Brighton, a quaint beach town south of London. Over the past decade, she’s written about music and culture for New York Mag, The New York Times, i-D, The Guardian, and previously worked as a staff writer for Dazed. She began working on the book seven years ago while working a day job she hated; it was around this time that Eloise, (who received her OCD diagnosis at seventeen), began to wonder if she was autistic. Thus far she had categorized herself as “uniquely obsessive.” It was after a draft of Obsessive Intrusive Magical Thinking was completed, but before the pitch went out, that she received her official diagnosis after a multi-year journey with England’s “free, but sh*t,” National Healthcare System. The diagnosis only changed a few lines of the book's introduction, but for Eloise, it helped her understand how her brain works and who she is.

With the book’s deep intimacy, it can be hard to imagine there was a time when Eloise wasn’t as forthright about her obsessions. For a period in high school, “it got beaten out of me a little bit and I calmed down and pretended to stop loving things as much,” she says. She practiced reflecting on her obsessions and referencing the meticulous journal keeping of her youth in her zine series Emo Diary, where she pulls direct quotes from her teenage musings on Fall Out Boy. These diaries — albeit less of the Pete Wentz portions — came in handy while writing this essay collection; some essays begin with epigraphs from deeply personal entries and others were only able to be written by referencing periods she had tried to block out.

Now, Eloise speaks loudly about her obsessions. “This is a generalization and it’s a stereotype, but we [autistics] tend to be more earnest,” she says. “With that comes a naivety. I got bullied a lot growing up and even as an adult. I won’t know straight away because I expect the best from everyone at all times. It takes a long time for me to realize if I’m being used or ostracized, but it also means that I’m very open.” By surrounding herself with alternative music circles, she has found friends who are more open to earnest displays of love and fandom (think mosh pits) and participate in mocked hobbies (think Adult Disneyland lovers).

As her peers post memes about their goals of a smooth-brained existence, Eloise imagines that would be scary. Her focus is to position her brain to work with her, not against her, and bask in her heightened capacity to enjoy things whenever possible. “Sometimes I do wish I could switch it off. It’s something I struggle with a lot. But, if I’m going to have thoughts all the time, I do my best to try to steer them towards good things rather than bad thoughts by doing things I enjoy.” While still certainly not a self-help book, Eloise’s commitment to focusing on what she calls “life-affirming situations,”—seeing Lorde three times in a month, walking on the beach with her dog, riding The Haunted Mansion all afternoon—is inspiring. For an overthinker who mused for 270 pages about the complexities of obsessions, her ultimate sentiment is reassuringly simple. “You can’t have any control over the bad things that happen, but if you don’t try to have those little moments within what you can afford and achieve that are positive, then what’s the point?”

This article was originally published on