Culture

Walk A Mile In Nancy Stella Soto’s Huaraches

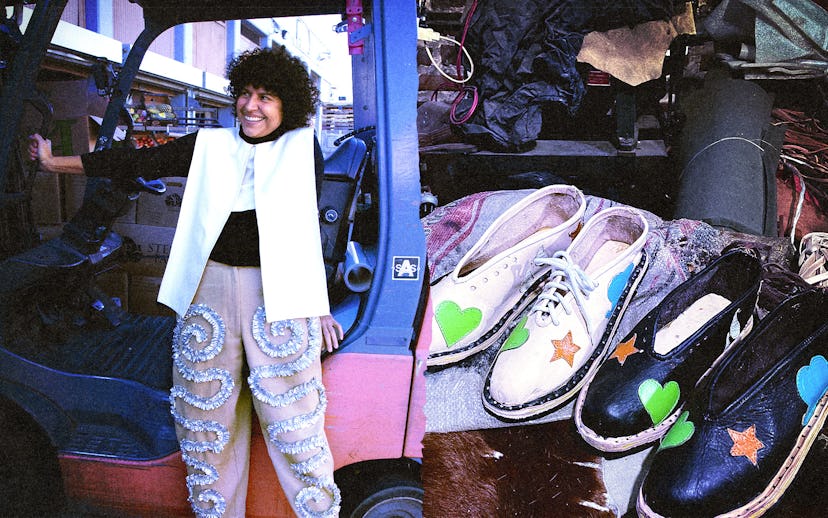

As the Hammer Museum’s latest artist in residence, Nancy Stella Soto taps into her roots.

Early in my visit with fashion designer Nancy Stella Soto, I notice a painting of a clown hanging on the wall. It’s an eerie scene, garish and carnivalesque, but presiding above the stacks of her bewitching clothing, the piece feels almost poetic. Knowing Soto and the milieus she circles, the clown could very well be a gift from some LA art star. So I ask, “Which artist made that?”

“That?” Soto snaps, breaking into her infectious, exuberant laughter. “I found that in a thrift store!”

Soto’s downtown studio — where we meet to discuss her residency at LA’s Hammer Museum — is crammed with many such objects blurring the boundary between treasure and trash. There’s a red signet ring crowned with a micro portrait of the hugging Hindu guru Amma next to a translucent green and yellow ear of corn. On her desk sits a framed photo of three smirking otters beside a huge black lighter with “Las Vegas” emblazoned on its side. The curios pair uncannily well with the racks of her own wildly imaginative clothing that perhaps more than any other line today flirts between the worlds of fashion and art.

That fluidity in part made Soto a natural fit for the Hammer’s latest artist in residence, a prestigious program with few rules, expectations, or restrictions. Sometimes a residency leads artists to exhibitions and performances, other times to research and study. In short, residents can do most anything they desire. Soto used the residency’s support to do the most Nancy Stella Soto thing imaginable: journey to the huarache capital of the world to create her first line of shoes.

In Michoacán, she went door to door asking strangers if they knew “anyone that still uses the nail technique” needed to craft huaraches in the traditional way. This sort of scrappiness remains baked into Nancy Stella Soto, both the artist and the brand. The entire operation unfolds within a few miles of her Produce District studio and Soto knows, intimately, all the hands that touch her garments.

You can see this ethos in the shoes she produced in collaboration with huaracheros. Stylish and avant-garde, the shoes possess a defiant rawness born from a DIY attitude and the necessity of resourcefulness: the soles are cut from used car tires and hammered together with toothpick-thin nails. Aesthetically and philosophically, Soto seems to be in conversation with a much wider audience than the boutiques in which her clothes often sell. Her work — architectural in form and bacchanalian in spirit — evokes everything from kimonos to cartoon strips, garbage bags to hot air balloons, picnics to yes, even bizarre thrift shop clown paintings. Soto elevates garments into something more like wearable sculptures.

“I'm always surprised when someone likes something that I make because to be honest, everything I make, I make for myself,” she tells NYLON. “And if anyone else likes it along the way, it’s surprising and rewarding.”

Soto’s journey from club kid to presenting her work inside an elite art museum is a uniquely LA tale. The story speaks to the city’s many conflicting impulses and drives: its punky underbelly, its glamorous facade, its relentless need for reinvention. And if clothing can do anything, it can give us the opportunity to become alternate versions of ourselves, to slip between different worlds, the high and low, the formal and playful, the serious and silly. Even if only for a little while.

Why is it important for you that an institution like the Hammer sees value in your work? I mean, I see value in your work…

Of course, I care that you like my work! I just think it’s also meaningful for an art institution to see value in my work as a clothing maker. What the Hammer curator, Erin Christovale, pointed out is that she appreciates how hyper-local and community-oriented I am. I source all my materials locally; everyone I work with is within a 5-mile radius. To be acknowledged for that feels great.

You grew up in LA around the garment industry. Paint a picture of your youth for me.

I was born in East LA, grew up in Highland Park, and for my high school years moved to Rowland Heights. When my mother migrated from Mexico she was a seamstress in Downtown LA. She worked for a leather goods company and was a buttonhole operator. When I was a very young child, I would sometimes spend the day with her at work. I was fascinated by the clothing-making process from a very early age.

I grew up with a single mother and my father was not that present. He worked in the produce industry and I think it's interesting that my studio is in the Produce District, or what I like to call the Piñata District. I have these constant reminders of my parents, their beginnings in this country, and how I evolved around those surroundings.

What was going through your mind back in those days?

I saw myself as an explorer. I was enchanted by the garment industry: the industrial machinery, the racks rolling around the streets, people pushing baskets full of cut fabric pieces before they are sewn together. Every business that it takes to produce a garment, I was around that from an early age and I absolutely loved it. [In high school,] I was definitely a goth, but the last year of high school I abandoned my gothness and became a raver. I was making party outfits and doing a lot of psychedelics.

What was your soundtrack?

Early high school would have been Skinny Puppy, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Sisters of Mercy, I think you can imagine. Later in high school the soundtrack became techno, house, jungle, and a touch of happy hardcore.

And you were going out to clubs?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Clubs, warehouse parties, and desert raves. We had fake IDs that my friends and I got in MacArthur Park. Mine had my actual photo and the gender listed as male and no one ever questioned it.

What was it like coming from this very immigrant world in the Fashion District and falling into that scene?

It was very natural. I mean, at least for me. For my mom it was not. She supported my curiosity with clothing and style, but was quite disgusted with my queerness. As a late teenager that was full of joy and excitement, being met with my mother's reaction was confusing and heartbreaking. I did find support with some of my very close family members. And all of my friends, many of whom were also queer. But at home I didn't feel like I could fully be myself.

Did you spend that time thinking you were going to start your own brand?

Not necessarily. I simply saw myself as an observer, an observer that was accumulating skills, I suppose. One of my jobs was working as a designer at a drapery company in North Hollywood, where I learned new skills that were different from garment manufacturing. I became interested in voluminous shapes and woven heavyweight fabrics. What I learned there I still exercise in my work today.

What finally made you say, “OK, I’m gonna start Nancy Stella Soto”?

I couldn't get a job. I completed a short program at Central Saint Martins in London and then spent six months in India doing textile research. I was away from LA for two and a half years. When I came back, I started applying for design jobs. I never got an interview or even a reply. There was nothing left but to start my own brand. I created a job for myself, basically.

I think of you as someone enmeshed in the art world with your work distinct from most fashion brands. It’s sculptural and having this other conversation. Tell me more about your relationship to the art world.

A lot of my friends are artists, writers, and creatives in general. I mean, as a creative person myself, who am I supposed to hang out with, Sammy?

But do you think your clothes are in conversation with the art world of which you're floating around? Or is it me projecting that onto them?

I see my clothes as just clothes, but I guess the point is I have to make it interesting for myself. I have to add some other technique or add another layer on top of the standard garment-making. When I make a garment, I don't just send it to the cutter and then the sewing contractors, I have to manipulate it somehow. I bring it back to the studio to draw on it or cut something away from it. There's an additional detail that I like to add on to the garment. It's my hand in every single piece.

Talk to me about your foray into shoes.

The Hammer residency made this possible. I've always been interested in shoes and a traditional way of making things, being resourceful with materials that you have access to. I'm Mexican so I thought I would use the huarache as my starting point.

A huarache is a traditional Mexican shoe made of leather straps. The huaracheros buy used tires, and they have metal dies in the shape of the sole. They cut out the sole of the shoe from the tire and form the leather straps around a last to form the shoe. They then hammer the whole shoe together with these small nails. That technique is not used all that often anymore because it's labor intensive and a lot of people have moved on to more modern techniques like sewing or simply gluing the soles together.

And how was your trip to the huarache capital of Mexico to produce these shoes?

I knew that I didn’t want to make a traditional huarache, I wanted to make a lace-up shoe, but using the traditional technique of the tire sole and nails. I went door to door asking people…and finally I was sent to these brothers that have been making huaraches for 40 years. They wouldn't bend though. They were not open to making anything outside of the two designs they have been producing for decades. Maybe I could change the color or the shape of a strap a little bit, but nothing too drastic. They suggested another huarachero that has been producing [them] for 55 years. I went to his house and described what I was interested in making, and he was open to helping me.

I assembled a sample as best as I could so he would have a visual of what I was trying to achieve. From there together we made the additional sizes. There was a lot of back and forth. I would go to another leatherworker that sews heavy leather to sew the appliqués onto the shoe before it was assembled. Then I would run back to the huarachero and we would layer all the pieces, glue all the components together, and then he would nail the sole. In the end, when he really liked the shoe that we made, that felt inspiring to me. He was like, “Wow, they actually look good!” I appreciate having that response.

You're such an LA figure to me. What about LA is moving to you at this point after having lived here your entire life?

All the people I get to work with, the integrity, and the love they have for their craft. The cutters, the sewing contractors, the die cutter, graders, garment workers in general. People have so much pride in their work and I love being around that energy.

For me, your work is this quintessential LA mix of cultural ephemera. Thrift shops meets high-end fashion aesthetics meets glamorous art world meets trash you find on the side of the street. Where does all that come from for you?

That's exactly how I've always experienced LA. Depending on the neighborhood you're walking in or driving through, that's what it is. It's a mixture of cultures, architecture, colors, eras, and they all come together. They can all be so different or they can all blend together, and yes, I think that's how I translate my environment, through my clothes. It's a reflection of the city I grew up in and the city that I love.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.