Culture

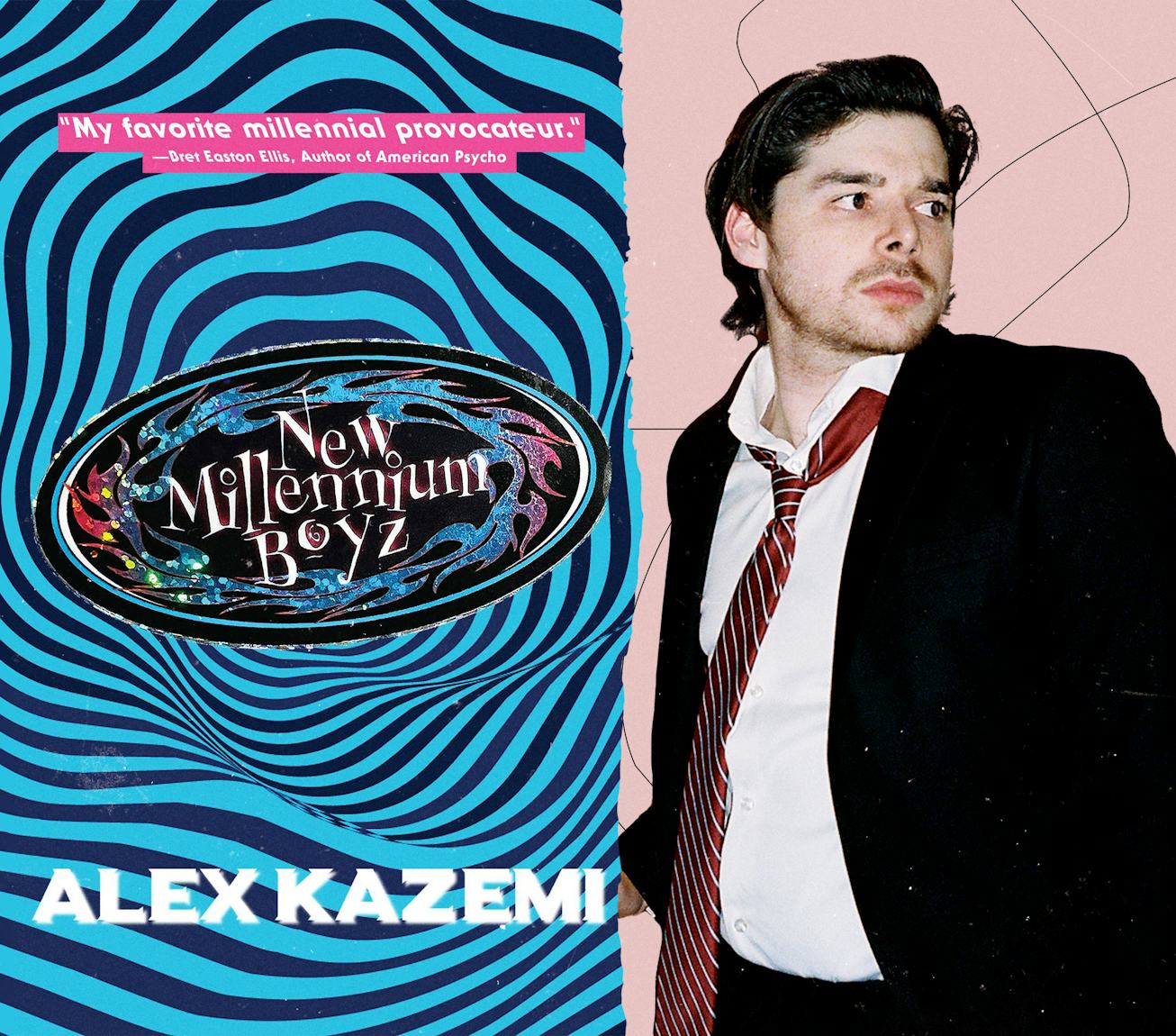

In New Millennium Boyz, Alex Kazemi Captures The Debauched Y2K Era

Alex Kazemi’s New Millennium Boyz is a debut novel with historical shock value.

Every generation thinks the world is ending. With Y2K, that fear was magnetized by a date on the Gregorian calendar, a day to fuel further infection of the throbbing wounds of snaggle-toothed teens’ apathy and disenchantment.

In recent years, Y2K has been given a nostalgia-dipped, revisionist history: We praise Britney and Paris; many of us are still nursing a Bratz doll obsession; we pretend to hate skinny jeans. But the year 1999 wasn’t a blinged-out paradise, it was a time of massive disengagement, soaked in the acid of violence of Columbine, gore blogs, and gay-bashing, among a slew of other gruesome cultural artifacts.

Alex Kazemi’s debut novel New Millennium Boyz is a VR trip into the sludge of 1999. The book, which is dedicated to “To anyone in this world who was born a boy” is a cutting, sometimes difficult to read, triumph unlike any other piece of media that has tried to capture the era. Chock-full of references to an almost parody level (they’re not just drinking Coke, but Friends-branded Coke), it is less of a time capsule and more of a primary source document written in the language of disenchanted, deeply unlikeable 17-year-old boys. Boys who listen to LFO, worship Blink-182, watch Girls Gone Wild commercials, and munch on Bart Simpson Butterfingers. Kazemi takes a jackhammer to our often reductive nostalgia of the era, revealing its debauched, sticky slime.

The novel, which is as inspired by Green Day’s “Jesus of Suburbia” music video as it is by teen exploitation films such as Thirteen, follows Brad Sela, a 17-year-old with Bret Easton Ellis-level panic, who sports a clear Jansport to school in the wake of Columbine in 1999. He’s thrust into the debauched underbelly of his Pacific Northwest suburb after befriending Marilyn Manson fanboy Lusif, who spends his time on Satanist blogs, and clinically annoying and deeply depressed Shane. Sela goes down a rabbit hole of brutalness, documenting their lives with a Handycam as they film increasingly brutal, shock-value acts.

“‘Don't be a pussy. I dare you to put the fighting fish on your tongue.’” Kazemi writes. “He leans over his band and pulls out a Polaroid camera. He takes the flopping fish out of the bowl. ‘Stick your tongue out.’ I stick my tongue out. ‘Now take your shirt off. Come on, pretend this is your Spin cover shoot.’”

Written more like a screenplay than a novel, the dialogue of New Millennium Boyz is chopped and screwed; scenes are interspersed with short spurts of dialogue, not unlike watching early reality TV. There’s not a strong narrative voice – what’s more interesting is the commitment to the form, both by Kazemi and by the media-seeped characters themselves – boys who so badly wish their lives were like the teen movies like Varsity Blues they also purport to hate.

Kazemi was born in 1994, though his proclivities could suggest earlier: He still has a landline, for example; he has no social media accounts; he mails hand-typed letters. The seeds for the novel began on Tumblr a decade ago, when an early version of the novel went viral in 2013, back when viral was a new word. It was picked up by the now defunct MTV Books, but Kazemi chose to spend the last decade honing it – diving deep into internet archives, old chat rooms, Geocities pages, and old Delia's catalogs in order to achieve a new video game-like verisimilitude to capture the era accurately.

NYLON spoke with Kazemi from his home in Vancouver, B.C. ahead of the book’s release about everything 1999.

New Millennium Boyz is available now from Permuted Press.

We were born in 1993 and these characters were born a decade earlier. Why did you want to capture this era specifically? There are aspects of this time that you share and remember, but it is a very different era from the one when we were teenagers 10 years later.

You are sort of the age group of the kind of reader I would want because we have those haunting feelings of, I remember the L'Oreal commercials. I remember the WB promos. I remember the world feeling a certain way. I remember the candy. But I don't know if you remember the Buzzfeed 2013 culture of “10 Things Teenage Girls Did in 1999,” lists, so I started with, innocently, what teenagers on Tumblr liked.

It was not a dark Y2K exposé yet. It was a backdrop to talk about my teenage feelings. I guess I thought all of the Y2K references were very cool at the time. As I got older and I lost more and more of my innocence and idealizations about that time, I needed to really analyze the real toxicity and the freedoms that people had back then, which ended up becoming a part of our cultural dialogue with the social justice culture. But it started out as an exploration of why were we all so obsessed with Y2K on Tumblr.

I know you did extensive research for this book, which we will talk about later. But how much of the cultural references came from your own memories?

It was definitely LFO - “Summer Girls.” LFO was a big one. “Steal My Sunshine” by Len was a huge hit in Canada, and I was lucky to find out that that was big in America, too. I think that my relationship with Y2K was probably about a bewitched enchantment of the pop culture of the era, not knowing that I was a part of the consumerist mass machine that Boomers were doing. Obviously I was a kid, but I think I was just enamored by the NesQuik commercials and how pretty Britney Spears was, and the whole MTV fantasy that they sold for me as a child was real. I was kind of getting high on TV and magazines and colors and all these things. It was a sensory experience.

You’ve said the dialogue was inspired by reality TV shows like Laguna Beach and The Hills. Can you talk about that?

In Laguna Beach, there are little moments of Lo and Lauren at Sephora talking, and it's a fast cut and they're doing nothing, and it feels like a real element of being at the mall and teenage life, but also sort of captures the emptiness, monotonous, teenage reality, though they're obviously very privileged and in a beautiful backdrop. But I thought, “How can I make this more surreal? How can I now use a snapshot of the boys smoking weed and talking, but make it about misogyny?” I was very inspired by reality TV, and that was the biggest war with my publisher because they're like, “What the f*ck? You're going to put out a book that's just dialogue and imagery and very low on narrative voice?” I was like, no, please trust me. I just wanted to make it almost like you're reading a script.

Is there anything that's been missing in coverage of your book that you've really wanted to talk about but haven’t yet?

A guy who's probably the same age as the characters born, wrote a review that said, “t really upset me how the book exposed how mean we all were” and that “I was very disappointed by the anti-nostalgia of the book.” I'm like, what do you mean? So you wanted to hold on to your delusional idea of how things were?

Why would you be so offended by anti-nostalgia? The historical revision idea of taking away that warm feeling that people associate with maybe seeing Silverchair on MTV and John Norris and all these things, maybe that feels hurtful, but we have to look at reality. I can't protect everyone's feelings. I can protect every man's idealization of how it was so great to jerk off to American Pie in their parents' bedroom. Let's look at how everyone else is being affected. Let's look at the big picture of how we were, because it is really nefarious to think of the level of pop brainwash going on as is beautifully illustrated in Josie and the Pussycats.

A perfect movie.

Josie and the Pusscats is my Goddard or whatever.

New Millennium Boys goes so far in terms of the hatred and violence the boys expel, as well as to shocking levels with the debased antics they film. What was the process of pushing these characters to such extremes like for you?

It was really sad. It wasn't fun getting to work on these scenes, but I felt like because I was studying the evils of hazing and fraternity culture and just the worship that young men have of older boys. Thirteen was the biggest influence on me and that movie did a number on me as a child. That was just so intense because I kind of remember girls like that, and it felt like I was getting an inside walk into the pain of their world and just sort of understanding. And obviously I was very inspired by the “Jesus of Suburbia” music video for sure. Why I took it so far was to just sort of illustrate the evil of teenage boys that we don't really talk about enough. We always paint these misogynistic images of teenage girls, and there's none of that era of how cruel and mean boys are.

You wrote the seedlings of this book a decade ago. Have you been working on it for the past decade, or did you have a more concerted effort in recent years?

A whole decade. There is such a catalog of teenage feelings. I had thousands of notes. Every time I felt something, it would go inside of a character and write things on notebooks, Blackberry, I had to do so much transcribing. The research was crazy because I had to go to university libraries to get access to message boards from Y2K and read catalogs of what, because girls used to post “what I wore today.” I tried to really make it true to what kids were wearing back then.

What do you hope people take from the book?

I do hope that there is an element of healing for people that can come out of this book, whether it's any sense of validation of the way people were treated in that era or their own teenage feelings. But I really hope that men who read it can have a sense of leaving like they’ve departed from that automated adolescent masculinity. I don't super perpetuate it in my thirties or forties or fifties. I hope there's something good that can come out of writing a book that was so terroristic.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on