Culture

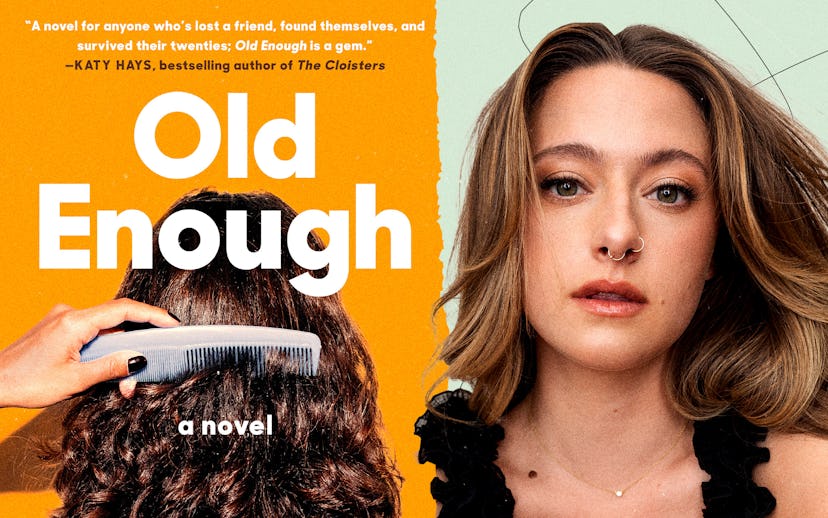

In Old Enough, Haley Jakobson Finds Meaning In The Mess

Haley Jakobson on Old Enough, girlhood, and creating queer family.

At the start of Old Enough, Haley Jakobson’s debut novel, our protagonist Savannah ‘Sav’ Henry is firmly in that strange, sticky place immortalized in Britney Spears’ seminal hit song, “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman.” She’s a sophomore in college, thoroughly out as bisexual amongst her new chosen family at school, but not far enough removed from her high school self as to feel fully-realized as an adult. It’s an experience Jakobson captures so tenderly that reading Old Enough feels like holding up a mirror to your younger self, no matter how far removed you are from that period in your life.

“As a writer, they say you write about the same things over and over again, and I'm totally fine with that. I think one of those things for me is girlhood,” Jakobson says. “I'm obsessed with girlhood: how it haunts us, how it heals us, the nostalgia of it, how it seeps into everything that we do as adults.”

Complicating matters for Sav is the impulsive engagement of her childhood BFF Izzie, which will bring her back into the orbit of Izzie’s brother, forcing her to confront and name what he actually did to her when they were younger. Facing dizzying panic attacks and memories viewed through a new lens, Sav understands that what happened to her was sexual assault, a reflection of an experience Jakobson had herself.

“I am very openly a survivor and so much of my journey into that identity has been parsing out the different narratives that told me why my version of survivorhood didn't count,” she says. “All the ways in which we talk about what assault looks like, sounds like, does such a disservice to so many people who experience assault and non consensual relationships with people. It took me far, far, far longer than Sav to have that identity within myself, and it was so important to me to write that story.”

Through it all, Jakobson lets all her characters be messy and imperfect, making their queer community even more real for all their collective flaws — and even more meaningful for how they help usher Sav through this period of her life.

NYLON caught up with Jakobson ahead of her novel’s release to chat about the tensions that come with finding yourself, why she views Sav as a younger sister, and what she hopes readers take away from Old Enough.

What was the inspiration for Old Enough?

More than inspiration, I knew that there were themes that I really wanted to write about in my first novel. That's really what started it all: What if I wrote a book about the difference between justice and healing when it comes to sexual assault? What if I wrote a book that really mines the grief and stickiness of best friend breakups and the obsession with twinning and best friends forever? What if I wrote a book about the queer chosen family and what that actually feels like, what the texture of that actually is? Because the media so often gets it wrong. And of course, one of those themes was also what it is to walk through the world as a messy bisexual woman, because, man, we need bisexual main characters in the media — there are a lot of us!

I related so much to the tension Sav feels between who you were at home growing up and who you are becoming in college. How did you tap into that feeling?

For me, as a Brooklyn-based, bisexual, queer person entrenched in this community, I certainly had impostor syndrome for a long time. I don't believe that Sav in any way is me — I see her more as a little sister that I've shepherded into the world — but we did both grow up in suburbia and in places where the expectations were we're not as fluid and as expansive as as now I see that they can be. There's this desire to prove how cool you are, how open you are, how — for lack of a better term — woke you are; to be queer sometimes feels like it's synonymous with having the moral high ground at all times. And that's simply not real or true.

But I think, coming into not only a queer community, but an artistic community, moving to a big city where there's lots of different people living lives in different ways, I certainly felt like I should hide parts of myself or the cringy parts of being a teenage girl and the decisions you made. You don't necessarily want to put those on blast as an adult woman, so I really wanted to write about how integration of self is so essential, and also so f*cking hard.

A huge part of the book is, as you said, finding and creating queer family, which is such a lovely experience, but it's not free of its own mess. What was the importance of creating that fully textural experience of finding your queer family?

Something that I learned much later in life is how necessary conflict resolution is — especially as folks who are assigned female at birth, we are not shepherded into the world with an understanding that disagreement and tension and conflict can be a very good thing. It makes it so that we can grow closer with one another, instead of siphoning off parts of ourselves because we're afraid to confront things that don't feel good in our relationship, continuing to pretend that everything's okay to the point of inevitable explosion and rupture.

I wanted to write a messy, queer friendship dynamic to prove to Sav and prove to other people that you can overcome so many things within friendship, and it brings you closer, not farther apart — that is actually the secret sauce for longevity in relationships. This obsession with having one person, your soul friend, your best friend forever and ever and ever, it can be suffocating. It can make it so that you never grow out and apart and into the person that you're meant to be. To let all of my characters exist in their complexities and knock heads and find edges with each other, and then still be able to come back together, for Sav, that is the most healing thing that she can experience. I think for so many people, especially women, that feels like love.

The undercurrent of Sav’s story is not just understanding, but accepting that what happened to her was sexual assault. How did you approach that particular storyline?

There's a link for me in my identity as a survivor and in my identity as a bisexual person, because both identities were shown to me in a way that didn't feel like me at all. What happened to me was not in the park at 9:30 at night with a hooded stranger, and my bisexuality wasn't promiscuity, it wasn't me flitting around from person to person, not being able to choose who I loved or who I wanted to be with. I didn't have a model for my queerness, and I didn't have a model for who I was as a survivor, so threading that together in one book felt really important to me.

I really did write this book in so many ways for survivors, a book that centers healing around the person who has been affected and not centering the abuser. So often the narratives do center the abuser, or they center stories of seeking justice — whatever the f*ck that means. And this was not going to be a book about that. This was going to be a book about how coming into that identity is not linear; it is very complicated, and at the end of the day, if you feel like something happened to you, that doesn't sit right with you and isn't wasn't okay with you, then we can call it exactly what it is.

Why did it feel important to you to tell Sav’s story?

She's very much a “too much” girl in a society that has asked her to be one thing, and she's not. She has all these identities clashing around and clamoring to be heard. It's this time in her life where she is hurtling towards the person that she wants to be. She's disconnecting from messaging that got stuck in her growing up and she's wondering if she does connect with the messaging that her new cool, queer friends want her to believe. She doesn't really have any answers. She truly is figuring it out.

I just needed to write a book where that was totally okay, and that it wasn't about the answers. It was about moving forward, and moving towards what feels like home. I think I also needed to write a story where a survivor was okay, and loved and safe, and was able to reclaim innocence. That is so often the thing that is ripped from us, so I needed to write that story for myself.

What do you hope readers take away from Old Enough?

In the book, there's a line that says you're never beholden to the person that you were yesterday. I hope they come away with that. I hope they come away with the realization that they deserve to be in a community that holds them and lifts them up and that they can make mistakes with and grow with. I hope that survivors come away from this story feeling really seen and appreciated and believed. I want so badly for any and every survivor to close this book and be able to say to themselves, “I believe in myself” — and know that I believe them, too.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.