Culture

How Fragrance Posting & Niche Perfume Houses Evolved The Scent Industry

A wave of young fragrance obsessives are revamping the stale perfume industry, one scent at a time.

Minka Ashley is a self-described scent pervert. She moved back a couple of years ago to her hometown on the coast of Maine, where she found herself with a closet full of outfits she never wore. Now, instead of changing her outfits every day, she changes her fragrances.

“I have a lot of really stupid outfits I love to wear, but I’m outside a lot,” says Ashley. “I’m on the beach and walking in the woods, so perfume has given me a little bit of luxury that isn’t expression through clothing. You can be in your outdoor clothes and still feel like yourself.”

Jane Dashley, a painter in Dallas, Texas, feels similarly. Dashley and her husband Jeff started collecting fragrances a few years ago and in 2019, started the Instagram page @Fragraphilia to document their collection, which they also do on TikTok. They staged photoshoots showcasing their favorite scents: bottles of Radish Vetiver by Comme des Garcons perfumes amidst a nest of radish roots or Chronic by 19-69 on a bed of fresh moss. They also recorded videos of themselves describing the scents in their collection, which now includes 71 fragrances between them.

“Suddenly, every girl I follow on Twitter that has cute style and is funny also talks about what fragrance she’s wearing today,” says Dashley, who has traded going out on Friday nights for perfume sampling sessions with Jeff, where they order samples and jot down notes.

“I’m not wearing a different outfit every day. I'm wearing a different scent every day,” Dashley says. “I didn’t really think there would be a time in my life when I was wearing literally the same outfit every day. I’ve worn an apron smock and LL Bean cargo dress every day for the last two weeks — but I’ve worn an amazing scent every day, so that really counts.”

While a couple of cool girls on Twitter does not a trend piece make, Ashley and Dashley are part of a renewed interest in perfume culture that’s been happening over the last couple of years — a cultural reimagining of the stale industry by people determined to preserve and promote genuinely interesting fragrances.

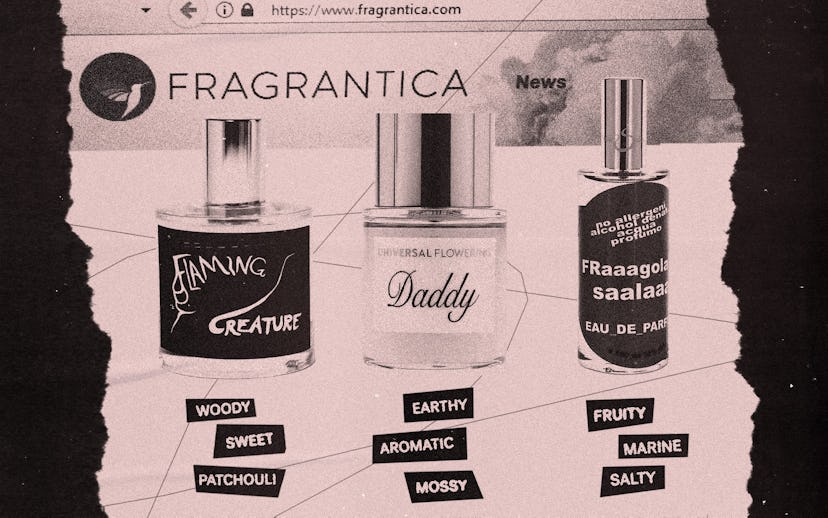

It’s a moment led by young people on Twitter posting screenshots from the HTML-era perfume website Fragrantica and tracking down ancient bottles of Shalimar on the perfume forum Basenotes, Etsy users selling bootleg decants, and TikTok creators offering the nichest of perfume recommendations. Changes in the perfume industry are being spearheaded by independent perfumers, like Marissa Zappas and Hilde Soliani, who are determined to make singular, engrossing fragrances, often by hand. People like beauty writers Sable Yong and Tynan Sinks, who host Smell Ya Later, a podcast about all things scent, are deepening our cultural conversation with perfume. YouTube fragrance influencer Jeremy Fragrance shares reviews for his nearly 2 million subscribers, and comedian Emma Vernon hosts the Perfume Room podcast and offers Zoom lessons on identifying fragrances, while photographer Elizabeth Renstrom stages bespoke Y2K mayhem photoshoots and posts “unhinged fragrance reviews” for her website Bass Note Bitch. The change is being led by even Jónsi, the lead singer of Sigur Rós, who last year built a “perfume organ” that wafted earthy scents into a gallery as part of his sculpture exhibition. It’s a change that’s as influenced by the pandemic as it is by websites like Scentsplit and Lucky Scent that have made it easier to procure fragrance samples, as it is by a larger movement toward hyper-individualism in beauty.

“I think a lot of it does have to do with, oddly, the brandification of yourself as an individual. Scent is just the next dimension of how you represent yourself and how you express yourself, so with our culture becoming super, hyper-individualistic, it just makes sense that your personal scent would add to that,” Sinks says. “Perfume was the last frontier. In my perspective, it started with color and went to skin care, and now we rolled those until the wheels fell off, and now it’s perfume.”

Perfume’s cultural moment is marking a shift in the stale perfume industry as well; the renewed interest that’s been building over the last few years is coming at a time when the industry is primed for change. For the last half a century, the perfume industry has run essentially the same way; the same people doing the same advertising and marketing campaigns, and largely the same perfumers creating fragrances.

“It’s like how many naked people on horses are we supposed to see, or naked centaurs? I don’t really think fragrance marketing is relevant anymore,” says Marissa Zappas, a poet and independent perfumier with a cult following whose name was mentioned by nearly everyone I spoke to for this story.

Zappas says it’s difficult for perfumers who work in commercial settings because of the enormity of the industry. Commercial perfumers have to crank out thousands of perfumes a year, leaving little time to be intentional about a new formula. As a result, they often wind up recycling formulas.

“Every perfume started to smell the same,” says Rachel Rabbit White, a poet and longtime lover of perfume who worked with Zappas to create a perfume to accompany her collection of love poems, Porn Carnival: Paradise Edition. “It seemed like they’re all going after a more cloying, sweet, younger sort of scent. I don’t know if that was just that they’re looking to grab a younger audience, or maybe it was that maybe the older audience, like millennials and older Gen X, who grew up on Bath & Body Works kind of scents, they were used to that gourmand vanilla, sugary type scent. I feel like that took hold over in such a way where even perfumes that might have been more floral or more clean suddenly got reformulated so they were now cloyingly sweet, and this happened to all of them.”

Part of the reason for the stagnation is because the fragrance industry relies heavily on market testing — which is inherently antithetical to how perfume is meant to be experienced.

“There’s got to be that first spray where you’re blown away, and I think that that really hits something in the brain, right? Serotonin, dopamine, I don’t know what it is, but it feels good to have this scent overpower you when you understand it immediately.”

“Scent in particular is really complicated, and I think within a scent there has to be one component that’s familiar and one component that’s unfamiliar for someone to take to it. The problem with everything on the commercial market is it’s all familiar. They’re really not groundbreaking in this way,” says Zappas. “We’re honestly at a little bit of a standstill and it needs to change. It hasn't changed in all these years.”

But the palette for unfamiliar scents is there — and sites like Fragrantica, which shows the top, middle, and base notes of perfumes with the same level of detail as you would if you were wine tasting, are helping people identify what they like and how to more easily seek it out from niche perfumers. Part of what makes fragrances like Zappas’ so compelling to people is that they contain notes that don’t smell like everything else on the market; maybe you won’t even like it at first.

“I like something to be 10 to 30% gross,” Ashley says, explaining that she likes having notes that feel different or weird, not like things you’d find at the counter at Sephora. That’s what makes scents made by Zappas, Hilde Soliani, Universal Flowering, Francesca Bianci, or other smaller perfume houses appeal to what Ashley calls a “younger, cooler” group of people.

“One thing that Marissa does is she is so genius at these bold openers in her perfume. I feel like when she made the Paradise Edition, people told me, ‘I feel crazy when I spray it,’” says Rabbit White. “There’s got to be that first spray where you’re blown away, and I think that that really hits something in the brain, right? Serotonin, dopamine, I don’t know what it is, but it feels good to have this scent overpower you when you understand it immediately.”

Zappas never sold more perfume than during the pandemic — and her sales remain strong, which she wasn’t necessarily expecting. She chocks this up to people’s relationship with self-expression changing: Now, people don’t so much as want perfume for going out, but for themselves.

“We’ve spent so much time alone with our own bodies that perfume has become something that we might not really wear as much going out, but more just wear for ourselves to try to get in touch with ourselves,” says Zappas. “I think that really, really says something about how interested people are in these kind of new sensory experiences and not just ordering perfume from Macy’s. They want something different; they want something more sensual, more thoughtful, perhaps even handmade.”

Hilde Soliani is one of the most beloved cult perfume makers, best known for her scent Buonissimo, meant to recall fresh brioche and Italian espresso. Soliani put her fragrances online a decade ago after shops refused to stock them because she wasn’t famous. That all changed about three years ago when Soliani became an underground favorite and was crowned the “queen of gourmand,” by Fragrantica, in the perfume world, though she tells me from her home in Parma, Italy, over Zoom, that she prefers a more expansive title: the queen of perfume. For Soliani, fragrance is an emotional, artistic expression.

“When I decide to create fragrance, usually I make it for myself, so I want to reproduce my emotion during, I don’t know, a visit to a museum, to the theater,” she says. “After maybe two, three hours, or 10 years, after the launch of my fragrance, sometimes I’ll stop during the night, and think: But why is this fragrance so successful? Because people recognize the sense in my fragrance, because my fragrances are my emotion, are my attention in my life.”

Nathan Omans, a research biologist in Brooklyn, got into perfume six years ago, after he smelled Replica Jazz Club by Maison Margiela. It smelled so unlike the ubiquitous trendy perfumes of the time, like Santal 33, a whiff of which he says “brings me back to walking down the streets of Williamsburg in 2017” — that it unlocked the role perfume could have in his life.

“I realized perfume could tell a story,” Omans says. “It wasn’t simply just something that smelled good. It was something that could evoke a memory or nostalgia or sense of place. The purpose of perfume became a lot more complex and more of an expression of art rather than something that’s superficial and for fashion.”

Now, he gets fragrance samples from Olfactory NYC and switches his perfumes every couple of months, using scent as a way to mark a time in his life — revisiting them later would be not unlike reading a diary.

While there still are It fragrances, TikTok has been instrumental in bolstering perfumers like Zappas and Soliani — as well as recommending fragrances outside of Sephora’s bestseller lists. Ciara White, a 21-year-old TikToker in Houston, posted a video where she gives perfume recommendations “for the sluts and freaknasties of our society,” pointing to a tweet that reads: “I need perfume reviewers who are sluts. Tired of the ‘wife-in-training’ taste levels I’m being delivered.” (For what it’s worth, she suggests Angels’ Share by Kilian, which she describes as “sex in a bottle.”)

“I think people want to be more fun,” White says. “They want to be more expressive, not the typical stuff their moms and grandmas are wearing anymore. I feel like people are trying to not fit the box anymore. That’s how everything is, whether it’s clothes or the way you wear your hair. Everything is about trends and people are breaking away a little bit.”

If trends are moving us in the direction of the persistent and ever-individualized cultivation of our own personal brands, scent is a largely untapped way to do that. But perfume is not only hyper-individualized, it’s invisible and genderless; you can’t see it on Instagram.

“Perfume has always been a way to flag something, your sexuality, your orientation. But I feel like that flag is just now more fluid,” Rabbit White says. “It’s more open-ended, more amorphous. I feel like that makes sense where we’re all at for our expression, our sexuality, as well.”

Zappas points to how perfume used to be political in the 20th century. Nina Ricci’s L’Air du Temps was released in 1948 following World War II as an ode to peace, love, and freedom — and was adorned with two entwined doves atop the bottle. “I think that part of the original draw of perfume when it first became commercialized in the early 20th century was the way that it really tapped into society and politics and really the zeitgeist, whereas right now commercial perfume just isn't as smart,” Zappas says. “I think that's really where people like myself are trying to come in and make perfume kind of relevant again.”

The fragrance boom deviates from most of the beauty industry thanks to its ease. Contouring and liquid liner are practiced skills, but perfume is glamor at its most effortless; your scent can speak for you.

“Fragrance is the one thing about beauty that you don’t have to look like anything. Anybody can experience it, anybody can participate,” says Yong. “I think everyone's really exhausted with just constantly trying to think about being in a body, and it’s f*cking exhausting. Fragrance is one thing that you’re like, ‘Oh, this is a part of beauty that I can participate in where I don’t have to look like anything.’”

Emelia O'Toole, who posts fragrance reviews and education for her nearly 300,000 followers on TikTok as @professorperfume says she often feels frustrated and exhausted by the barrage of beauty content that tells her what not to do.

“By the time I’m dressed for the day, I’m exhausted. … And it’s just like, oh, my God, free me. I just love that fragrance is one and done,” O’Toole says. “Fragrance is the one thing where it’s like, it doesn’t matter what my makeup or my hair or my outfit looks like that day; I can put it on and still feel as confident as if I’m full glam. Fragrance is this pure form of self-expression that doesn’t ask anything of me but to spritz it on.”

For Sinks, perfume is also about talking up space. “We are all so socialized to be as small as possible and blend in and blah, blah, blah. And whether it’s with fashion, with makeup, whatever, not to be Beyoncé about it, but we’re told to shrink ourselves,” he says. “Fragrance is the antithesis of that. It is a direct action to make yourself bigger, not only in the room with the space around you, but it's taking up space in people’s memory.”

“It’s just not something that is defined by any conventions really,” Yong says. “If someone compliments and is like, ‘Oh, you look so pretty.’ I’m like, ‘Cool, great. Yeah, I put a lot of effort into this. Thanks.’ But if someone tells me, ‘My God, you smell so good.’ I’m like, ‘I’m yours.’”