Culture

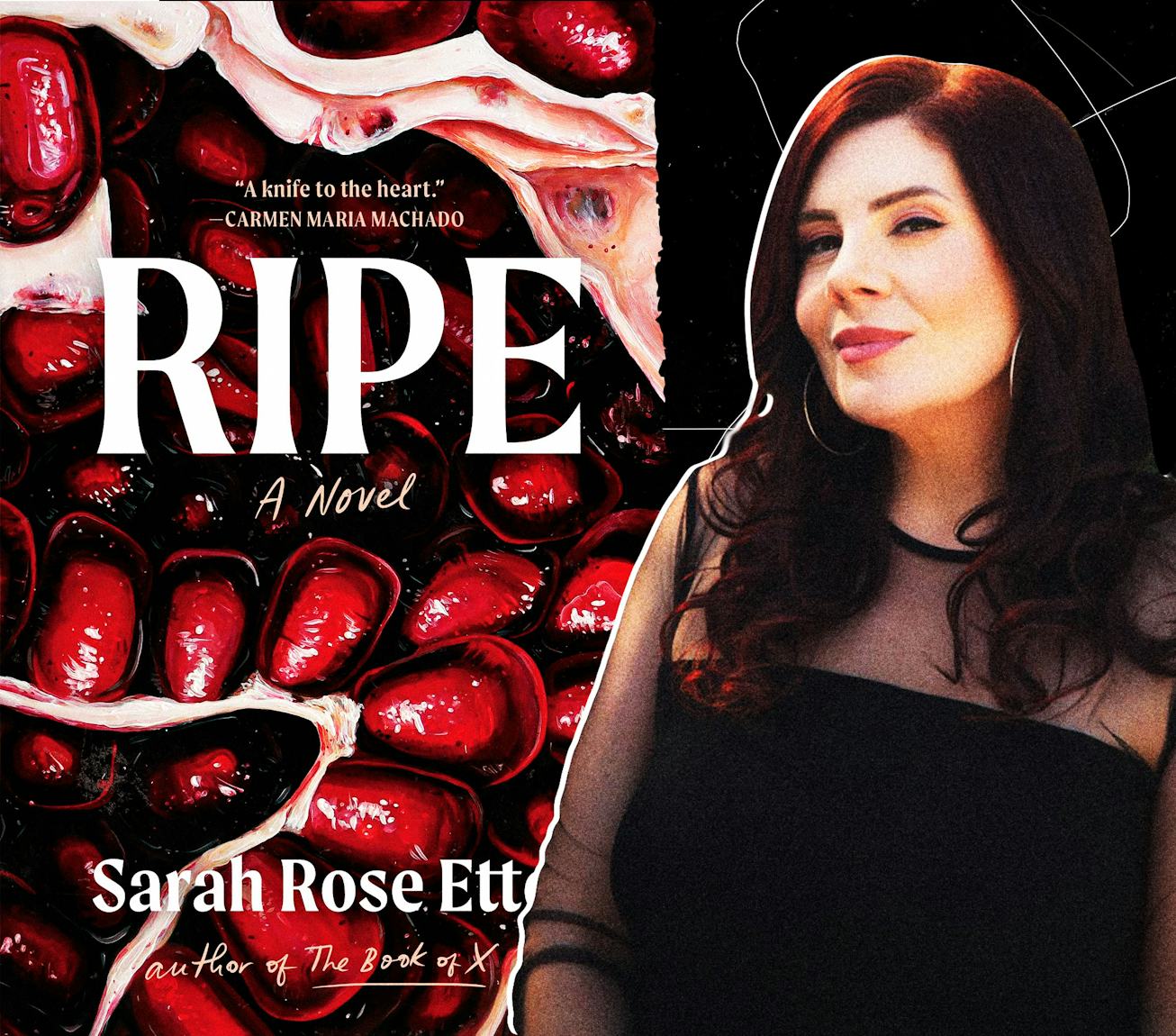

Sarah Rose Etter’s Ripe & The Rotted Underbelly Of Capitalism

“I’m not an empath, but I definitely have an antenna, and the energy was just so jangly.”

Sarah Rose Etter is a prophet for the sad girls. In her two novels, 2019’s The Book of X and 2023’s Ripe, two women navigate life’s uncertainties while a surreal element follows them. In the latter, it’s a miniature black hole that dilates in relation to our protagonist’s anxiety and depression. A recent hire of San Francisco start-up VOYAGER, Cassie has trouble with the illicit tactics her company uses to get ahead and the juxtaposition of exorbitant wealth next to homelessness and inequality.

Etter wasn’t thinking of writing an intentionally sad novel or following a recent uptick in melancholic literature like her peers Ottessa Moshfegh or Sally Rooney, but rather, it was what the story required. Her inspiration came from writers like Joan Didion or Sylvia Plath, who “allowed their characters to be sad and authentic and didn’t try to to turn it into a redemption story,” Etter tells NYLON. “I was having a sad girl time.”

Cassie becomes increasingly entrenched in VOYAGER, working with “Believers” who are relentlessly optimistic about the promise of capitalism’s offerings, a boss that’s cruel to her in private, and extended workdays, all while harboring a secret pregnancy. She uses drugs in the middle of dinner parties to dissociate from her life, but the black hole always looms large, a constant threat.

During her year working in tech in San Francisco, Etter routinely witnessed suffering around her, some of which invariably worked its way into Ripe. One day at a coffee shop, a barista warned her to be careful, as just the previous day a man lit himself on fire outside. “I felt I was standing on the edge of the world and it was collapsing around me,” she remembers. “I’m not an empath, but I definitely have an antenna, and the energy was just so jangly.”

Cassie’s story is a dark look at the underbelly of capitalism, but one that Etter felt she had to write. “People ask you to write a hopeful book, but when I was in San Francisco, looking around, I didn’t see any hope there. Unless your hope is tied to a white guy with a great idea,” she says. “I had a version where [Cassie] girl-bossed out of there, and she reported them to the New York Times — it just felt so fake. I felt more interested in telling a story that was true than a hopeful one.”

NYLON sat down with Etter to talk about the novel’s pomegranate form, the real-life inequalities that shape her work, and surrealist ideas.

You play with form here much more than in your previous novel, with diagrams of a pomegranate, definitions of words that relate to Cassie’s life, and between each section are notes and research on black holes. What was the inspiration behind this switch?

I wanted the book to be like if you were holding a fruit. If they would have let me publish it in a circle shape, I probably would have gone for it. I was thinking about how to make writing as sculptural as possible. Sometimes when I’m writing a novel, the structure helps me finish the work, because I need everything to be in a container. When I started to think about the pomegranate, each section began as a way of looking at her life. The first section is the outer rind, and it’s her job, and where she lives. Then it gets a little deeper and deeper and finally we get to the seed, where she’s pregnant and trying to deal with her body. Some of the things are just tent poles for me as I try to figure out the shape of the story.

The definitions were meant to function as the way memory works, which is, if you smell a certain perfume or hear a certain song, you get this immediate flashback. I don’t love backstory, I don’t love saying, “When I was 15, blah blah…” That’s most of the pushback I would give during editing. I am not for that. The definitions were a way to give you exactly as much information as you needed about her so that you could understand her decisions and why she’d take this job, why she’s so obsessed with money.

We see classism and inequity in its purest form in Ripe: girls go out to brunch while protestors walk through the streets and homeless people sleep at the foot of mega-corporation office buildings. It’s clear the seeds of these ideas are based in life in 2023, but how did you seek to emphasize these ideas, bring them to their fictional extremes?

I think I was trying to get the sensation of when you’re reading really terrible headlines on your phone. That idea of panic, being overwhelmed by multiple things happening at once, it’s meant to show her as an individual up against all these systems that she can’t control. Climate change, the housing crisis, the economy, her body — she becomes shrunken in the face of all these things happening around her.

I wrote this shortly after going into lockdown, when we had the Black Lives Matter protests. I was at the one in Austin, and the police department brought out the tear gas and shot rubber bullets, and gave people literal brain damage from how abusive they were. They were tear-gassing people even when I went into my apartment, all of this was happening under my balcony. It really gave me PTSD. I think that moment was super formative for me and I just didn’t know what to do with it.

I think the same thing is true for the man who lives under [Cassie’s] window. I had a man who lived under my window in San Francisco for the whole year that I was there and I didn’t quite know what to do for him. You can give food, you can give money, but I couldn’t get him real help. That’s another thing where you’re sitting there in this moment, like, “What do I do with this? Why is this happening?” I think Cassie is a way for me to try to figure out what’s happening and why.

In both of your novels, there’s this surreal element: The narrator of The Book of X had a genetic knot twisting her stomach, and in Ripe, Cassie is followed by a small black hole throughout her life. What makes you go for these fantasy-like elements?

I think it’s nice to have something for the reader to project onto. For me, the black hole in Ripe is actually my grief after my dad died. For Cassie, it’s depression, for you, it might be anxiety, for someone else, it might be anger issues. We’re all carrying something along with us, that sometimes gets so overwhelming that we can’t handle it, and other days, it shrinks down, and we can have a nice day at the beach. The surrealism gives some space to try and understand these giant emotions we walk around with, and sometimes we don’t talk about, because it’s embarrassing, or we feel like we’re the only ones.

I think the cool thing about surrealism is that the reader can meet you at a new place, and they can project what they want onto it. When you think about surrealist artwork, so much of it is about your own subconscious and how you’re coming to the painting. So much of it actually is not about what the artist intended, it’s how you engage with it. I’ll say this, too, I can’t be bored while I’m writing. A traditional plot with nothing ever weird happening, I don’t think I could do it.

What’s something that you want people to take away after reading this book, or your fiction in general?

I think that they're not alone, probably. That sounds so silly, but The Book of X and Ripe are both about a character named Cassie, so I think she’s running alongside me. She’s kind of my outlet for all of the weak and vulnerable things inside me, things I shouldn’t say, or tell anyone. Whenever these books come out I’m always floored that people read them and tell me the hard things they’ve been through. Even though it’s really overwhelming sometimes, I’m really grateful. It means we can start to talk about depression, or capitalism, or those days when you really don’t want to go to work, but you have to put on a face. Something really horrible could have happened to you right before we got on this Zoom, and you’re still here, and I wouldn’t know. After my dad died, I kind of got obsessed with figuring out, like, “Where did he go?” and the black hole is the most natural thing to look at, because it’s this doorway to infinity, or not.

Ripe is available now via Scribner.

This article was originally published on