Culture

‘The Elissas’ Is A Harrowing Look at Y2K Youth

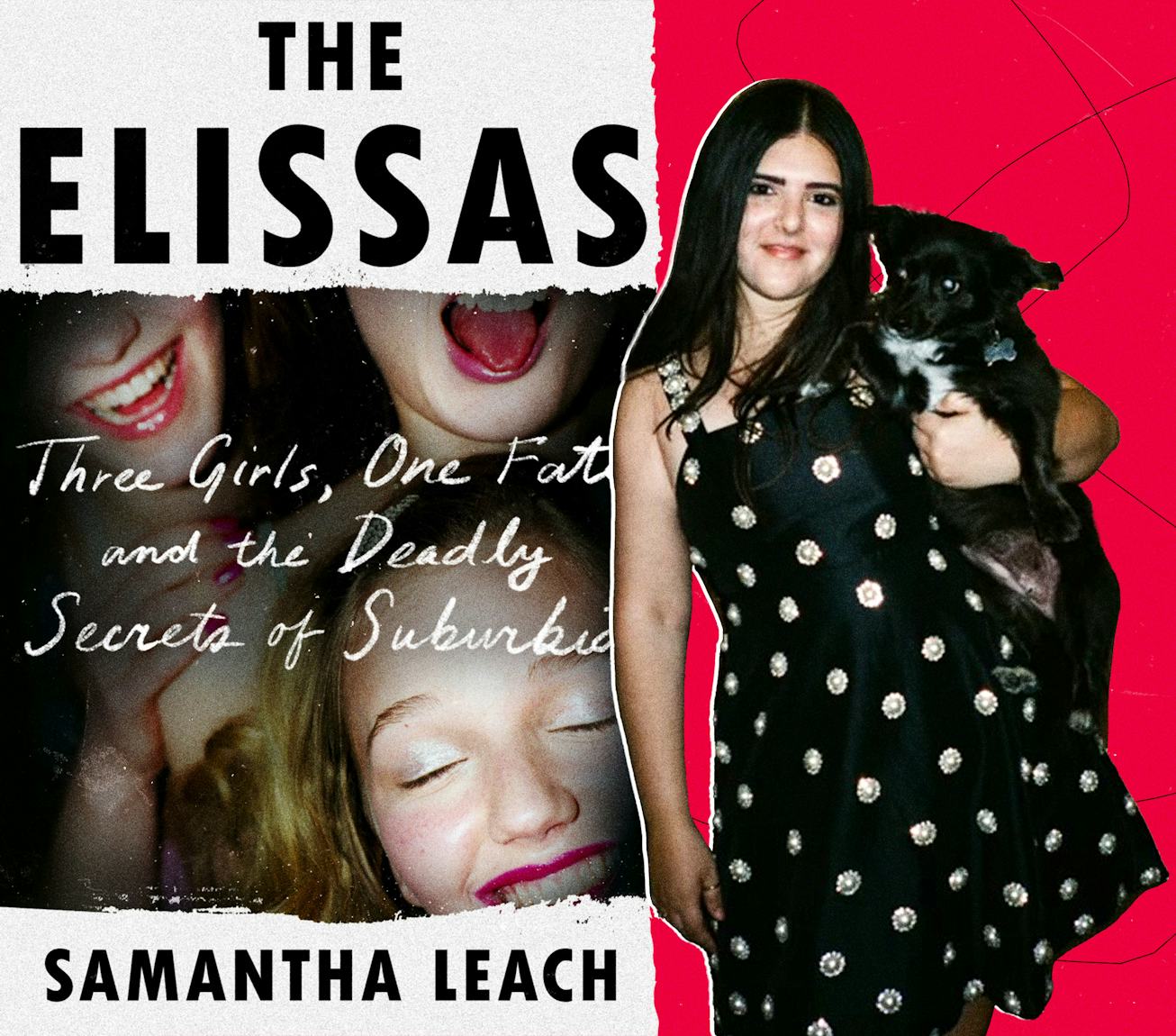

Samantha Leach’s debut tackles the troubled teen industry is also a coming-of-age story, told in a glossy era with a sinister underbelly.

For pre-teen Samantha Leach, Paris Hilton was God. She still might be, we agree over a glass of wine at Corner Bar in the West Village, where Leach wrote much of her new book, released last Tuesday. But for a subset of women coming of age in the early aughts, there was nobody quite as exalted as Hilton and Nicole Richie: These women, with their tiny dogs, unlimited shopping budgets, and penchant for partying, were nothing short of aspirational.

“We both watched The Simple Life religiously and treated our viewings like finishing school,” Leach writes in the early pages. “Elissa mastered Paris Hilton’s baby-voiced, come-hither demeanor while I studied Nicole Richie’s sarcastic, sardonic schtick.”

It’s this era that serves as the backdrop to Leach’s monumental debut book The Elissas: Three Girls, One Fate, and the Deadly Secrets of Suburbia, which follows the story of three girls: Alyssa, Alissa, and Elissa, all friends, the former of which was Leach’s childhood best friend, who all attend Ponca Pines, a therapeutic boarding school that’s part of a vast network of private, unregulated institutions that make up the Troubled Teen Industry, and by the age of 26, were all dead.

In The Elissas, Leach explores with robust research the factors that contributed to their demise, individually and collectively. She traces a time punctuated by opioid overprescription, the valorization of raunch culture, a lack of adequate mental health care, and most glaringly of the Troubled Teen Industry, a for-profit world with no governmental oversight that proliferated in the era, leaving many of its survivors with scars — sometimes both physical and emotional.

It’s also a coming of age story, one told in a glossy era with a sinister underbelly, like the pain and pleasure of Snake Venom lip plumper. Leach references S.W.A.T.ing, for example; the dangerous 2009 “prank” where people would call SWAT teams on each other’s homes, or “Rainbow Parties,” where girls would dole out blowjobs like party favors, that I recall hearing about on Oprah when I was in elementary school. The Elissas is the most accurate accounting of the time I’ve seen thus far, an ethnography told in The Simple Life and Girls Gone Wild, in Juicy Couture sweatsuits and pit-stained Abercrombie graphic tees.

But for all of Leach and Elissa’s reverence of Hilton, the cruel irony is that Elissa ended up just like her: The party girl who got sent to be reformed by a Troubled Teen Industry school, which only exacerbated her struggles.

Leach submitted her book proposal the week after the release of Hilton's groundbreaking 2020 documentary This Is Paris, which details in-depth the abuse she and a vast network of survivors suffered in the Troubled Teen Industry.

The timing fueled Leach’s research; suddenly a topic that had been clandestine was being uncovered in a series of exposes. And this week, Leach and Hilton converged again, this time more explicitly: Hilton tweeted about The Elissas, a moment Leach wishes she could share with Elissa, as well as with her younger self.

“Elissa was the Paris, and now I feel like Paris and I … not we're all on the same path, but to be circling each other in any way, I wish I could tell my younger self,” Leach says. “I wish I could tell her this stuff, because if she knew, that would've been like, ‘holy s*it.’ I think that's why so many people have come forward, because I think Paris was this avatar or literally God for us — particularly for girls who end up in the Troubled Teen Industry, young rebellious women at that time.”

But there’s a fourth heart beating at the center of the story: Leach’s own. It wasn’t Leach’s intention, but the book inadvertently became an exercise in healing an inner child — one that, despite all her love and worry, could not save her friend from so many larger, more sinister forces. The Elissas could have been a book about the Troubled Teen Industry and three women affected by it, but what makes it so psychically arresting is Leach's own feelings. She is the foil to the girls who didn’t make it, and not because she didn’t party, which she did. But in one pivotal scene, she decides not to follow a group of friends who go off to do Oxy.

“Another thing that was really important to me and really weighed on me as I wrote this is that I didn't want it to be the classic story of, ‘She had light hair. I had dark hair. I was studious. She wasn't,’” Leach says, referencing Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. “I wanted to make sure I was thorny and complicated in the book. I've done drugs. I could be a b*tch. I'm not perfect and I never wanted to present myself as anything otherwise.”

Watching Leach come to terms with everything that happened, using her own lived experience of an adolescence in the republic of size 0, sex tapes, and opioids to trace her own vulnerability — and ultimately her own healing — is the glitter glue holding it all together.

NYLON caught up with Leach ahead of the book’s release to talk about the Troubled Teen Industry, Paris Hilton, raunch culture, and other famed party girls who faced tragic demises.

The Elissas is out now from Hachette.

I'm really interested in how you structured the book. One thing I kept thinking about was how much of yourself you decided to put in and what that was like.

I would say that one of the earliest models for the book was Three Women. And because Lisa [Taddeo] didn't put herself in, I was sort of like, "If Lisa Taddeo didn't have herself in there, I shouldn't be in there." But also I think that thing of, “everyone thinks they're special and their story is interesting,” — I was really hesitant.

I was really hesitant to be like, "I should exist in this story." So I put myself in bits and pieces, and then I wrote the funeral chapter, where it was really a lot of me, and that was the moment that I really felt like I kind of cracked the code. My best friend Abby said to me after reading it, "We have to really care about you to care about this book, because even though you're not one of these women, you are who's telling this story."

I think I didn't quite glimpse how to do that until I wrote the funeral chapter and then really went back from there and was like, "Okay, that was the chunk of flesh on the page." I was like, "How do I trail the blood along the rest of the chapters?" I think that was the turning point for me.

What was it like to write that chapter? When did that come for you?

I wrote the book linearly. I went chapter by chapter, and I revised as I went. I would send each chapter to my editor and go in real-time. Until we nailed a chapter, we didn't go on to the next. I probably wrote that chapter in the summer. It all blurs together. I think that with chapter, elements of it had existed in the proposal. Elements of it had been with me for a long time. Elements of it were in an essay I wrote in college. But the story actually became much different, other than Hebrew prayers and certain things that just felt so essential.

For some reason, I had only eaten eggplant Parmesan that whole week that she was dead, because I really liked the eggplant parm from this one place in Providence. My mom bought a tray of it, and I just remember waking up every day being in the same gray sweater, eating a hunk of eggplant parm, and then just going upstairs and crying. In earlier drafts, there was just a lot of eggplant. The details you focus on change.

I felt like the first time it was a lot of "Wild Horses" by the Rolling Stones, a lot of eggplant Parmesan. I think once I learned what it was like for the women that I interviewed who had traveled in for the funeral and I situated them in that space, I then almost viewed it as what it would've been looking like if we were all sitting in opposite rows and kind of staring at each other, but seeing through each other. So that became the vantage point, which really tweaked what I focused on in a way that I think was for the best. No shade to the tray of eggplant Parmesan but it did not make it into the final cut.

Paris Hilton is almost a character in this book, she's so representative of what you wanted to be. I love when you write about wanting to be a slut. I remember that want viscerally. The cruel irony of all of this is that the girls were like Paris, but not in the way that they wanted to be.

It's the cruel irony, the way that Paris has loomed so large in my life, I always joke that I just wanted to know her so badly that I was like, "Maybe my dad would date her." You know what I mean? Because my dad was single, and she was, like, adult. I mean, she was God, right? She was what a cool girl was: ideal womanhood.

So, then to be reexamining that relationship to the standards that early aughts set as she came forward and then became a big part of reclaiming that experience and her time in the troubled teen industry…Elissa was the Paris, and now I feel like Paris and I, not we're all on the same path, but to be circling each other in any way, I'm like, I wish I could tell my younger self.

It’s also the same feeling I wrote in the book. "I wish I could tell her this stuff," because if she knew, that would've been like, "Holy sh*." I mean, I think that's why so many people have come forward, because I think Paris was this avatar or literally God for us, particularly for girls who end up in the troubled teen industry, young rebellious women at that time. "Comfort" is a weird word, but I think there's that feeling of being seen by someone like that is a really incredible feeling for survivors.

We are old enough and mature enough now to be able to re-skin this era and think about it differently. I have never been so aware of the ways that Paris and Nicole affected my concept of self. e The era we came of age in was really crazy in a lot of ways.

It broke our brains. I think people ask me, particularly with the body image stuff, was ours the worst ever? And I'm like, no. The people who came up under the Kardashians will be struggling, too. There's always new pressures and everything, but that doesn't mean each one isn't individually and specifically harmful to the girls who come of age in it.

I think about it the most in terms of body image because that's what I've struggled with the most throughout my life. The moment that all those celebrities became “Zoebots” …I loved The Rachel Zoe Project. I was obsessed. I wanted to be boho chic. I wanted all those things. When it turned from being Juicy sweatsuits to clavicles … sweatsuits, we kind of all can do, but there was something specifically about the way those muu muus hung on their bones that just felt, "Oh, this is particularly breaking my brain."

You really unlocked some core memories for me from the early and mid-aughts. For example, the Rainbow Party detail of this “blowjob era.”

It was raunch culture. It was Girls Gone Wild. It was the real advent of the sex tape. As I was going back and researching [blowjob culture], it’s like, "Is this only in response to Monica Lewinsky?" And I'm like, “No, this is pure sex tape culture.”

It was totally Girls Gone Wild. Like, I will be rewarded for being a slut.

Think about the graphic T-shirt culture at the time. I'm sure there were so many "slut" t-shirts: That was what “cool” was. I read Ariel Levy's Female Chauvinist Pigs, which I did learn a lot from. But if you're an adult woman examining teen culture, then you have the POV to be analyzing it. But if you're a teen and you just see people being cool and having fun, then it's like, that is what cool and fun is.

I love A24, but I think that I can watch it with a stylized lens. But I think if I were 12, Euphoria and Spring Breakers and The Idol would've been, to me, what Girls Gone Wild culture was back in the day. I just would've been like, "I'm on a merry-go-round to get a guy's attention; where's the molly?" We imprint on what we watch. It's not novel, but that's true.

It is fun to revisit the early and mid-aughts because it really was ridiculous in so many ways. But it’s also dark, because all of this contributes to everything that happened.

I think particularly, and getting into “The C-Word Podcast” with Lena Dunham and Alyssa Bennett calcified a lot of these ideas, but just like, the labels we place on people, those prophecies become fulfilled: If you're told you're troubled, if you're told you're slutty. It's also this idea that everything is romantic until it's not.

Everyone wants to be a Marissa Cooper, a Paris Hilton. But guess what? Marissa Cooper dies. That is a death that feels inevitable, and entirely preventable, and shocking all at the same time.

I got really into Edie Sedgwick when I was younger. I did not watch Factory Girl thinking it was a bad movie. But Edie dies. They all die. And it's the same thing. Entirely preventable, incredibly inevitable. That's fully how I feel about that trajectory.

Even in the book, somewhere in your bones, you knew, with Elissa.

I had a lot of fear. I was a fearful kid. I was always worried about my parents. I was always worried about Elissa. I really feared for her safety. I did not feel as if she had much regard for it. I do think that's part of being young, that we think we're invincible. I really felt it with her in a way that was deep in my bones, a real concern for her safety.

Did you ever find your grief coming up in your many conversations with people for the book?

I wrote about it a little bit more with one of Alyssa’s friends, who I really found to be my counterpart for her. I think, though, I had a lot of grief for these women at large and their collective experience. I felt as if I had maybe at that point worked through a lot of the Elissa stuff because I had just been thinking, and feeling, and reflecting on it for so long.

What I had a harder time shaking off was the people who would tell me about being locked up in rooms, or denied medical care, or stripped of their basic rights. I think when it was the end of the night and I felt like I was having a dark night of the soul, it was less about that pain of losing Elissa, because I'd spent a decade mourning that, and more really just distraught that I felt like I was speaking to anybody's lived experience – just really privileged to be let into their stories, but really heartbroken for what they'd experienced.