Culture

The Chilling World Of ‘Slonim Woods 9’

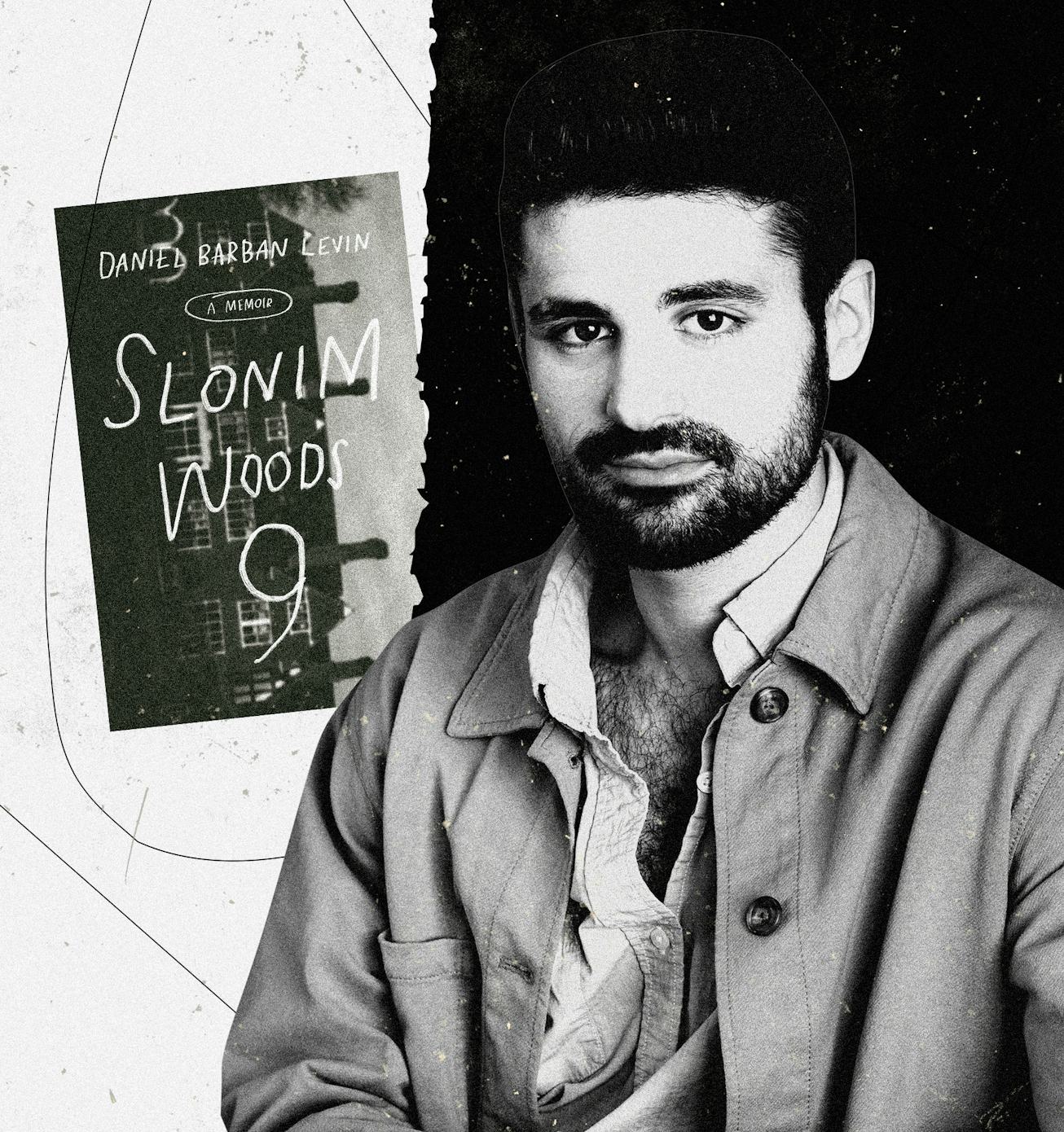

Almost a decade after escaping a cult, Daniel Barban Levin finally gets to tell his story.

Daniel Barban Levin needed to find an apartment in New York City for the summer between his sophomore and junior years of college. He ended up joining what he now describes as a cult instead. In the early 2010s, Levin and several of his friends were drawn into the dangerous orbit of Larry Ray, the parent of one of Levin’s friends at Sarah Lawrence College, which he attended from 2010 to 2014. Ray was a master manipulator who drew vulnerable students into his grasp by holding one-on-one coaching sessions, where he promised to help them “achieve clarity.” Levin met with Ray at a Starbucks for one of the sessions. Afterward, he walked outside, where it was now dark and a limousine filled with all his friends was waiting for them; they had been talking for six hours.

Soon, Levin was living in an apartment in Manhattan with his friends and Ray, where he experienced physical, mental, and sexual abuse. According to Levin, Ray’s main tactic was gaslighting: He’d manipulate — often with violence — group members into confessing they broke something and then would extort their families for damages that he insisted needed to be paid. In 2019, the New York Magazine cover story “Larry Ray and the Lost Kids of Sarah Lawrence” detailed the experiences of Levin and others, and in 2020, Ray was indicted by federal prosecutors for sex trafficking, extortion, conspiracy, and other charges. He is currently awaiting trial.

It wasn’t until after the article came out that Levin realized he needed to be the one to write his story — especially because Hollywood was interested. “Soon there were a lot of powerful men trying to tell my story for me, and suddenly folks in Hollywood, all these adults were fighting over this story of trauma,” Levin tells NYLON. “None of them were the victims, but they wanted to make it into entertainment and I just couldn’t stomach it, so I started writing. I just wanted to tell my story.”

But writing a memoir after being gaslit and abused poses some nightmarish psychological gymnastics: How do you trust your memory after someone intentionally did everything possible to make you doubt it? What are the ethics around telling other people’s stories? Is writing an art of emotional cartography or self-reclamation, or something else? How do you take back a story you were told wasn’t yours?

Levin tries to untangle these emotional Gordian knots in his memoir Slonim Woods 9, a disturbing, extremely vulnerable and extraordinary account of what happened to Levin and the emotional and psychological fallout. Of course, nobody plans to end up in a cult , which makes the book so tantalizing: There’s both a morbid curiosity to learn what happened and how and why — but an even bigger impulse to see Levin come out the other side.

And while Levin eventually escaped, not all his friends were so lucky. The book is dedicated “to the friends I cannot reach,” which Levin tells NYLON is less a naive hope that they’ll leave Ray’s grasp, but a longing for who his friends once were. “It makes me really sad because what I wish is that none of this had ever happened and I guess when I say ‘to the friends I cannot reach,’ I’m talking about people who existed many years ago, who I can’t reach across time.”

NYLON talked to Levin, who is now based in Los Angeles, about the experience of excavating trauma and taking back a story that you were told wasn’t yours.

At what point did you decide to write a book about this experience?

That’s a great question. I talk about it at the end of the book; it’s hard to define when you start writing something. There’s a moment after I left the situation living with my friend’s dad in Manhattan and being a part of this abusive group and not really understanding what I was going through while I was going through it, and I started dating someone after I got out and there was a point where we were walking in the city. And going back into New York City, still to this day, is a reminder of the trauma and brings things up I didn’t understand then.

We were talking casually about that time, and I hadn’t really told her that much about it because the way I understood it, it was just my friend’s dad and he was an intense guy. I mentioned to her offhandedly that, “Yeah, he hit me at some point,” that was kind of a thing, and I realized at some point that she wasn’t next to me anymore because she had stopped in the street and was crying, and I was shocked. I didn’t understand what was strange about that because it had been so normalized for me that this violence was expected, deserved, not a big deal, something they do in the Marines. It didn’t occur to me that it would be totally inappropriate for a friend's dad to be hitting kids.

She and I sat down and I explained the whole thing to her and it was as if a mirror was held up. I started to really see what had happened to me and slowly from there, work to be able to call it what it had been, which was a cult. At the time, I had no frame of reference because most people I think have a very specific definition of what cult is. That was years before I started writing this book. But I started writing from then, trying to write it in poetry, trying to figure out how to make it make sense to other people, all the while also trying to hide from the people I thought might come after me and try to hurt me if I said something bad about them. And now we’re here, talking to you.

When was that conversation with that girlfriend?

It was the end of senior year at Sarah Lawrence or maybe in the summer immediately afterward, right towards the end of finishing school and going out into the world. Of course, part of this whole experience was just in college, it's sort of this fulcrum; you’re turning into the person you're supposed to be and part of how this happened was that I just didn’t know how to live in the world or certainly how to find an apartment in New York and had this horrible dry run where this guy offered me his apartment, and I had to try to figure out how to do it all over again once I escaped.

When the New York Magazine article came out — you had a quote that really stood out to me. That article was so big and led to Larry being arrested and I’m wondering how the article affected your life? Where were you in the process of writing this book when that came out?

The first thing I should say -- I was trying to hide and protect myself for years. I got out of this and described the process of extricating myself in the book, but part of how that happened was I had to try to lead these people to believe that I wasn’t turning against them because I knew what it looked like when someone became the enemy. I had to sort of slink away and hope that no one would follow me.

For many years, I was hiding, and maybe the best way to reframe this is that, in this experience, I encountered a man who was such a skilled storyteller that he could tell you a story about you, your life, and what had happened to you and your memories, and you would believe it more than you believe yourself. I left and I was just trying to figure out how to rewrite my story and figure out what was real and what had happened to me and I was doing that for years. I think most people, if they get a call from some reporters saying we're working on a story about your friends poisoning some people, they’d be surprised. What they were telling me wasn’t surprising at all, except I thought, there was no way this group would be sustainable for years. I thought surely it’d fall apart and what they were telling me is it had been going on the whole time I was gone and this man's story, his version of the world, was surviving. Now it was spreading beyond the group because people were believing the types of accusations I’d seen over and over while living with my friends and him in this apartment, which is that one of us hurt someone or poisoned someone or damaged something, which was not true.

It became my responsibility to tell my story, the version of the events from my perspective. At that point, just to correct the record for my friends’ sake. I wasn’t anywhere in writing this book at this point beyond the poems I had written, because my background is poetry. What happened after the article came out was that soon there were a lot of powerful men trying to tell my story for me, and suddenly folks in Hollywood, all these adults fighting over this story of trauma. None of them were the victims, but they wanted to make it into entertainment and I just couldn’t stomach it, so I started writing. I just wanted to tell my story, and so I did that and we’ll see how that goes.

Is this book at all part of the healing process or an act of self-reclamation?

It was somehow simultaneously both traumatizing and healing. In the process of experiencing the abuse, I talk about it in the book, but in order to survive it you put it in a windowless room and when you're being abused you have to go back into that room, but you know it's separate from everything else in your life. When the abuse that day is over, you walk back out the door and the door disappears behind you and now you're back in your normal life where that’s not happening. So I had to reopen the room and take the walls down. I had to go back inside of it and in this book, what I try to do for other people — I wanted so badly for the people I encounter in the world to understand just a little bit what it's like, maybe selfishly, to feel less alone — but I didn't want to traumatize anyone the process. It was, how can I re-enter this room and make it safe for me and for a reader? I think what ended up happening, not intentionally, was that it’s as if I put walls back up around it, but glass walls, so it still feels safe to me; it's encapsulated. But now I can look at it a little more clearly. I can walk around and look at it from each side. So I don’t know if it healed the trauma, but maybe it was a stepping stone towards being able to do the processing that is necessary to heal, and I think it has expedited that process.

“I didn’t understand what was strange about that because it had been so normalized for me that this violence was expected, deserved, not a big deal, something they do in the Marines. It didn’t occur to me that it would be totally inappropriate for a friend's dad to be hitting kids.”

This is a weird question, but are you familiar with EMDR therapy at all? (EMDR therapy, or Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy, is a psychotherapy method that helps people recover from trauma.)

Yeah. Why do you ask?

What you just said reminds me of what you’re trying to do in EMDR. You’re having to revisit this room, but you’re making it a safer place so that you can look at everything. That’s just really interesting.

That makes sense and I should say that in the writing process, that was also happening in a literal sense. I moved across the country to California and interestingly, without it even occurring to me, I moved into an artist's loft, and I was living with seven other people, sort of replicating the experience. My therapist says this is something our brains do naturally is try to access echoes of the traumatic experience, but in a safe way to process. So I moved in with all these people, but they were all wonderful. And if I was writing a chapter that took place in the living room of this apartment, I’d go to my actual apartment in California and go into the living room and it felt as if I was in both places at once.

I read that therapy was difficult for you because it mimicked Larry’s treatment. How were you eventually able to begin to heal to get to a place where you could even start to write this book?

It’s so complicated. The path of healing from trauma is not straightforward at all. The first therapist I went to, I tried to unload it all at once. My whole body was shaking and all my muscles were spasming; I could barely do it, but I was trying to say it and watching the face of this therapist and her jaw was on the floor and she didn’t really know how to react. I think it was really hard coming out of this and feeling constantly like no one has any frame of reference for it, so no one’s going to understand and they’re either going to look at me like a freak, because when we think about people who are cult members we think of something particular and it’s not “us.” So it would mean I’d be held at arm's length, even by a mental health professional.

When I talked to those reporters and time went on, I was thinking more about it. First of all, for myself, I wanted that not to be true. I thought that if I wrote this book maybe it would mean that people would understand this experience a little bit better and breach that gap, not just for me, but for my friends. There's a support group in New York that I went to for people who had escaped cults and that helped democratize my understanding or complicate my understanding of what a cult survivor is or what a cult is. There were people in those support groups that were in what most people would describe as an abusive partnership, but we were talking about it in terms of cult dynamics. All of this helped me see myself inside of this a little bit more.

When you were writing this, were you able to talk to anyone else who’d been in the cult with you to help remember details or process or anything?

No. I wish. I’m not sure how much I can even talk about it, because of the trial that’s coming up. Essentially, for the sake of preserving the authenticity of each person’s memories of their experience, sort of trying to not cross those lines, which is really hard because you go through an experience with a man who, the whole design of the experience seems to be around making you question your memory of what’s real and what happened. The act of me writing this book was sitting down alone and saying, “Someone did everything they possibly could to make me not trust myself and my memory of certain events,” and now I just have to say, absolutely, “I trust myself.” This is an act of self-confidence that I believe what happened. I believe my account, which is still terrifying.

Were you scared, or are you scared, about the possible fallout from sharing your experience?

Every day, in so many different ways. The most obvious: One day I was living in the apartment where I wrote the book, and a guy — and it’s LA, it was someone with mental health issues or something, the apartment was on Sunset Boulevard — was slamming on our door and I looked out my window and this person had a knife. My mind immediately jumped to: They sent someone to kill me. This is where I’m at in terms of fear for physical safety. I’m afraid of fallout because I told my story, but my story involves a lot of other people’ stories, people who have been victims of the same thing I have or adjacent versions, who are going to feel just as bad about having someone else tell them what happened. So in the book, I try to address that, especially in the last chapter, I talk directly to that. I thought that what I wanted was for everyone in my life to know what had happened to me. I thought on some level they can just read the book and we never have to talk about it again, but that’s not how anything works. It turns out that something that is so hard for you is hard for the people who love you in a different way. Those conversations aren’t easy. You have to take care of yourself and take care of other people and it’s really hard.

You dedicated the book, “to the friends I cannot reach.” Are you hoping you can reach them through this?

I think what I felt when I was writing the book was that there were all these people I loved who had been a part of the fabric of my social world. The friends you make in college are the foundation of your social life for a lot of people for the rest of their lives — and that whole part of my life has been blown up. I try not to harbor any delusions about being able to change anything, being able to reach anyone. I think the best thing I can hope for is that maybe other people who experienced anything like this, other people who are in my position where they really don’t know what to call what they’re experiencing or what they’ve gone through, whether they’re in it or out of it, if I can reach one of those people and maybe it helps them help themselves, that would be amazing. To be honest, it makes me really sad because what I wish is that none of this had ever happened and I guess when I say, “to the friends I cannot reach,” I’m talking about people who existed many years ago, who I can’t reach across time.

How did you take care of yourself while writing this book?

Not very well at all. During the process, I had to relearn not only how to trust myself but how to trust other people, because if you have a whole group of friends and then they turn into a cult, it’s hard to want to have friends again. Something that’s supposed to be reassuring and supposed to give you safety in fact feels dangerous. I was so lucky, I felt like I couldn’t believe what had happened: I moved into this apartment in LA and suddenly I had a group of friends who are all amazing and new and not the people I knew in college and had nothing to do with them. If I went through writing a particularly retraumatizing chapter, I could then go into the living room and watch a movie with some of my roommates. I got to live in the present and would dip back into the past. I was dating someone who was amazing and really supportive and all these things grounded me, so I had this firm foundation and then I could step off the foundation and go into the deep water and have something to come back to.

“During the process, I had to relearn not only how to trust myself but how to trust other people, because if you have a whole group of friends and then they turn into a cult, it’s hard to want to have friends again.”

Has anyone who's in the book seen it or have you gotten any response from them?

I think that I actually can’t comment on that one.

What was the most challenging part of writing this book?

There were a lot of things that were really challenging about writing it. In some ways, writing the book was less challenging than the process — and I’m having a great time talking to you — but the process of talking about writing about this is harder, because the experience was all about loss of control. Someone else got to take control and it’s as if whatever part of you that you look to to make decisions or to tell you what is right and wrong— this guy was there instead.

Writing the book, I got to retake control and it was hard of course to make every little decision, trying to remember what people said and is it appropriate to put an exclamation point? All these things, you’re excavating your trauma and then figuring out how to make it consumable for someone else is really, really hard. But what’s so scary for me now is not the writing: It’s going to go out into the world and I can’t control that. I can’t control how people react to it. There are going to be people who don’t read the book who are going to want to talk to me about it. I'm having such a lack of control now that I'm having to work on accepting, which is really hard.

It’s one thing to write a book and it’s quite another to have it going out into the world, especially when it’s so deeply personal and about your trauma.

Right, and every day there’s a new version of the hardest ethical question you’ve ever been asked, at the highest stakes imaginable.

I mean that’s part of the challenge of memoir, of course, but this is an extreme example of that challenge.

Right, I guess so. I wish I had written another one, so I had something to compare it to. I certainly have developed an immense amount of admiration for anyone who does this, because it’s so strange and I don’t think I appreciated how strange it is to try to write down what’s happened to you until I was doing it.

Slonim Woods 9 is out now via Penguin Random House.

This article was originally published on