Culture

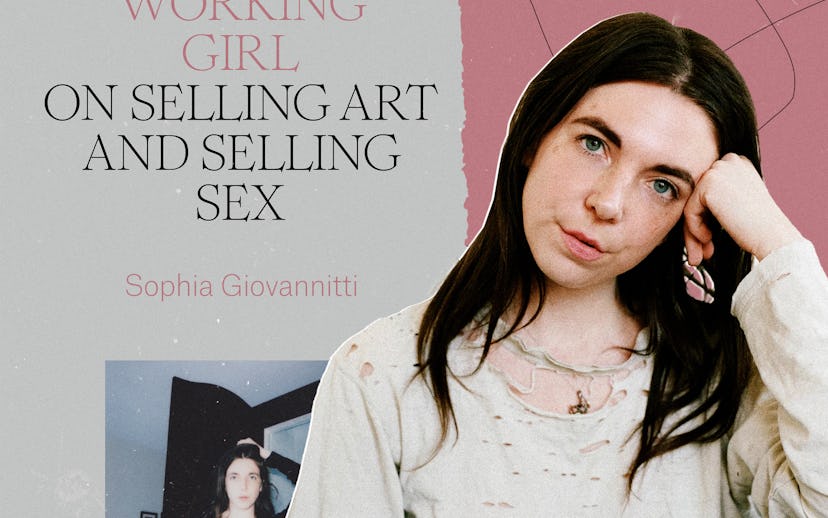

Art, Sex, & Anti-Capitalism: A Conversation With Working Girl Author Sophia Giovannitti

“I just have to make money in some ways, so that I can spend the rest of my time doing what I want to do.”

Sophia Giovannitti does not dream of labor. She dreams of so much more: “Strange sky-worlds; the dirty ocean at Rockaway Beach; the ecstatic feeling in the middle of a second glass of wine; the juvenile romance of blood oaths,” she writes in the last pages of Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex, which was published last month by Verso Books. “Of cops swallowed by a wave/ Of prison bars spontaneously turning to dust… Of staying in bed all day/ Of everyone doing exactly as they want.”

Giovannitti is an artist and sex worker, and her poignant debut work of nonfiction Working Girl is a blisteringly thorough, measured study of sex and art — two romanticized realms that we sometimes like to pretend exist outside the crushing system of capitalism. (As if!)

“To me, the art world and the sex work world — sure, there are things that are unique about them, but also to me, they’re both just intensified microcosms of things that are just sort of true about social and work life under American capitalism in general,” Giovannitti tells NYLON.

Sex and art are beauty commodified. Both can annihilate you, both are sacred; life would be pointless without either. As both an artist and a sex worker, Giovannitti asks: What does it mean to sell a piece of yourself?

“I used to want to be making art with everything I did; I wanted it all to count. I know now that it doesn’t,” she writes. “I just have to make money in some ways, so that I can spend the rest of my time doing what I want to do.” It’s this dream of doing what she wants to that is the driving force at work in the book. And one of the things Giovannitti wants to do is make art, which costs money.

The first time I encounter Giovannitti’s work isn’t in the pages of Working Girl, but rather in her small studio, in a Chinatown walkup over Dim Sum Go Go, where she is performing her lecture Scorpion, Frog — a phrase borrowed from a fable quoted in Season 2, Episode 10 of The Sopranos, which is arguably Giovannitti’s favorite work of art — for about 10 people. In the center of the room is Sophia Zero, a 3-D printed sculpture of her body on all fours that can be broken in two. (“The sculpture cost $3,000 to fabricate and $500 to get scanned,” Giovannitti told Cultured.)

During the 90-minute lecture, she talks about revenge, refusal, and exploitation, telling the story of a wealthy client, a woman whom she loved and worked with, and the various imbalances of wealth and power within the dynamic between the three of them. She ends the performance by describing a lake, one she fears she will never get to the other side of. I left the performance, like I finished the book’s last pages, in a trance. My eyes were watering, my body heavy, but I felt euphoric. There was so much to hold, so much to consider, so much wrong with so many systems — but what breaks through all of it is Giovannitti’s willingness to interrogate it.

In addition to sharing personal stories regarding sex work — which she resists valorizing, describing it as “neither glamorous nor creative nor fulfilling” but “precarious well-paid labor, as mundane as it is strange” — as well as her art-making, Giovannitti delves into the history of persecution of prostitution. She begins with the Page Act of 1875, which resulted in the exclusion of almost all Chinese women from the United States, and goes on to detail the ways various systems prosecute sex work in the name of protecting women, while they’re actually policies that harm them. It’s also a survey of sex in art, excavating works like Untitled, where the artist Andrea Fraser sold a recorded video of her and an unidentified art dealer having sex to the dealer for a reported $20,000, as well as the work of Paul Mpagi Sepuya, whose erotic photographs foreground Blackness and queerness.

Much of the book, much like in life, is about survival under capitalism, in a society where we have to give parts of ourselves away. But its best moments are when she finds pockets of air amidst capitalism, like her dreams she details above. Giovannitti has ways to exist outside a “formal economy,” as she describes in blissful detail.

“And that is where pockets free from capital lie, where meaning itself lies: in the ours that we neither possess, nor regulate, nor fully understand, but encounter and float within and steal, like a bioluminescent sea, or a CitiBike we joyride in the woods upstate, grown mossy and rusty from laying, rogue, in a creek,” she writes. “Incidentally, such an our is often found through art or sex.”

NYLON spoke with Giovannitti about living outside a “formal life,” how much of herself to put in the pages, and how satisfying it is to be able to have money to make the art she wants.

Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex is available from Verso now.

Where did this book begin for you?

I guess probably more like the fantasy aspect or just some of the theoretical underpinnings of it was what I was ultimately going to write as an essay series. This was pre-pandemic, it was probably 2019 or 2018 or something. I was re-reading Theory of the Young Girl, which I reference a bunch in the book, and thinking about this whole milieu I was in of art girls, sex workers, never knowing how people were earning money, a sort of conspicuous consumption and everyone being “broke” and just feeling a lot of confusion about it and then thinking, “OK, I’m in a really particular scene.” I’m talking about these two extremely moneyed and stratified worlds, especially in New York. I want[ed] to write about it and write about what it means to occupy that position within those two worlds.

I had vaguely started working on it, and I think it was because of the pandemic, it was just sort of one of these moments where I think I felt both ambivalent about writing it, confused if I wanted to write it as fiction or nonfiction, confused how much I wanted to expose myself, what exactly I wanted to say. And so I put it to bed for a while and fell out of touch with that editor and magazine.

At a certain point, I continued on that road and deeper into those worlds, and so I remained interested. I was getting more and more interested in writing something longform and getting less interested in writing piecemeal essays. It sort of came out of that, like, “OK, I want to write a longer form book length piece and this is what I want to write about.”

I learned from Scorpion Frog that your grandfather was a labor leader and also a writer. You also write in the book about being from a family of artists. How has this impacted what you think about work, or how you approached the book?

I feel like my whole relationship to work — specifically labor or my thoughts on that — and then creative work and making art and writing has definitely been shaped by my family specifically, my family history. I was always made to think about work conceptually a lot growing up. I’m not saying that that’s common or uncommon, but I think that that just was a big theme in my family because of this history.

I never met my great-grandfather. He was dead long before I was born, and his son also died right before I was born. But I saw my grandmother a lot, who had been married to him, and they had met in the context of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers union. This whole union and workers’ rights history was really imbricated with my literal family lineage and reproduction. I also have a lot of workaholics in my family, and I’m definitely not a workaholic.

I think something I’m focused on at this moment is understanding more about the specifics, contradictions, and complexities of that family history, and how it relates to me. I didn’t want to put it in Working Girl because I don’t know why, honestly. I think it just felt like I needed to get all this other stuff out first, just about my own experience. I think now I’m like, “Oh, I can kind of understand the intertwined-ness of all these trajectories more.”

What’s most interesting to me is the gendered element. Both of the public-facing writers in my family were men, both of whom I never met, and both of whom were really amazing, really creative people in a lot of ways. And also both had elements of brutality, and misogyny, and that came out of their own gender trauma and bullsh*t. I think that is something that I’m really working on now making work around that. It’s all in the book, but I think in a much more just spiritual sense as opposed to literal sense.

How much of yourself did you want to put into the book? How did you decide how much of your own experiences with clients or art-making that you wanted to share?

I think I am a person who, for better or worse, I really give into a lot of my impulses and prioritize my own desire, knowing that it will change over time. I think for a lot of reasons, it just feels nuts the way I learned to write: reading the confessional essay during the personal essay boom. I’m sure that a part of me is like: “This is what will sell this story and make a publisher want this.” I like attention, I like being provocative, all these sorts of noble and hideous reasons.

I think we’re all there, while I think being cognizant of this idea of “I might regret that.” I think the book having come out, it feels extremely jarring to see everywhere “sex worker Sophia Giovannitti,” which is such a f*cking idiotic thing to say because it shouldn’t feel jarring. That was obviously what was going to happen. That’s how it was all intended. It’s not to say that people shouldn’t say that; it just feels weird. You can’t actually anticipate how you’re going to feel. I think I’m just like, “OK, that is what it is.” And I’m curious how it’ll play out.

I mine my own experiences to make new things. That’s why I’m so interested in narcissism, because I feel like my practice is extremely narcissistic. So whatever happens with this, good or bad, it will ultimately lead to whatever I do next, which could be totally reactionary and making abstract imagery that has nothing to do with myself. Or it could be more of the same.

I keep going back to this idea of living outside of a formal life. It’s something I feel like I’ve dabbled in, working in nightlife. Why do you think so many people resist this kind of life?

I think there’s a lot of ways that it can be really hard. It just totally depends on who you are, what you want, what your class position is, your gender, your race. Obviously just all the things around access and having access to making different kinds of choices about your life. There’s a lot of people that live outside the formal economy that don’t want to, of course. I’m not trying to glorify it because I would hope that everyone has a choice to be within or without the “formal economy.” But I do find anti-work theory really interesting. I quote Kathi Weeks at the end [of my book], and her book The Problem With Work is super interesting. I think it’s honestly so interesting now with all the AI stuff where there is this kind of feeling of: “Why is society structured around work, especially American society?”

I think structure can be really important. I’ve definitely had times in my life where I’ve been like, “I just need to get a job. I have too much time to whatever, loll around and worry about things.” I don’t think that feeling reliant on a structure or wanting something to structure your life is bad at all. I think a lot of people are quite dependent on that or OK with it. I also think there’s a lot of people that would want to, whether or not it would even be work, would just want to spend all of their time doing something other than the current job that they’re spending all of their time doing. I think it would be really great if that was more possible.

American capitalism is just so specific and is both so hostile to the worker and creates the structure in which some work is the entirely dominant thing. I think it is really interesting in creative industries. This essay that just came out [“Bad Waitress” by Becca Schuh, published in Dirt], there were a bunch of quotes from it that I really liked around dignity and work, and how the life of the “American worker” is so undignified. That all felt so relatable.

I think sex work can get really sensationalized, and also because of that, I think it can be a pretty good example of a lot of things. Also with the book I was really trying... To me the art world and the sex work world, sure there’s things that are unique about them, but also to me they’re both just kind of intensified microcosms of things that are just sort of true about social and work life under American capitalism in general.

I really loved the end, when you talk about this idea of being “out of Empire time.” Moments like drinking a Coke in Venice with your boyfriend or getting sunburned on a raft. This world that you end the book on, one where you can make the art that you want and you can pay people well, is really hopeful.

I think it is super hopeful. One of the most satisfying things to me about making good money is being able to pay people to do the things that you want them to do. It’s also being able to hire people. It’s also obviously great and amazing to be able to give your money away and all that stuff, but also in just a totally selfish way, I’ve just been astounded by how expensive art production is and also how easy it is to do whatever you f*cking want and have it be seen in whatever way you want if you just have a lot of money to spend on it. That’s what has made all of my own autonomous art production possible. And I feel really conflicted, as you can see in the book, about all the things that went into that happening and everything.

I feel purely and totally satisfied by having been able to make the work that I want to make exactly the way that I want to make it. That’s the thing that I feel luckiest about. And then simultaneously to that, which feels just another side of the same coin, being able to have the experiences that I want. Being able to go to Venice, and go see all this amazing stuff, and see my best friend’s work there, and stay in a hotel with my boyfriend, and all these things that, sure, are luxuries and also are absolutely, to me, what makes life meaningful. I do feel like that is totally possible even under the sort of conditions that we live under. I feel like those are also the moments for me to remind myself of, OK, that is what I’m kind of living for and that is what I’m looking to expand in my life.

No, exactly. And it’s what we all deserve, too.

Exactly.

It shouldn’t be a luxury.

People should get time off, and people should have money to do the things that they want to do.

This article was originally published on