Culture

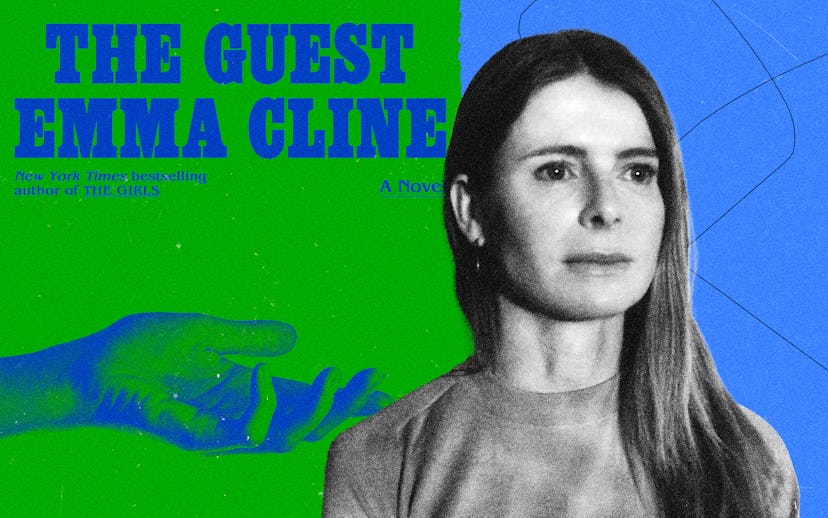

Emma Cline’s The Guest Is A Sun-Drunk Grifter Story Set In The Hamptons

The call is coming from inside the house in Emma Cline's latest novel, The Guest.

In Emma Cline’s The Guest, 22-year-old Alex never forgets to smile. She smiles to herself while pumping an eyelash curler, while fixing her part, while requesting a vodka soda at dinner parties where she’s bored out of her mind. She smiles despite the persistent stye drooping her left eyelid. See, if she stops smiling, people might ask questions.

The Guest, Cline’s third book, following her 2016 novel The Girls and 2020 short story collection Daddy, is an intoxicating, sun-drunk work that tells the story of a hand-to-God grifter, one whose head you’re both terrified of and want to bask in forever, until you wake up sunburnt to a crisp.

“I feel like a lot of the things I'm drawn to writing about, like power and sex and the performance of gender, it's like [Alex] embodies them or amplifies them in a more extreme way,” Cline tells NYLON. “I've always liked Tom Ripley-style characters. It's fun to watch a consciousness assess a social situation and navigate their way through it outside the bounds of our accepted morals.”

In the novel, Alex, a former sex worker, shacks up Simon, a wealthy older boyfriend in the Hamptons, until he kicks her out after she makes a regrettable social infraction at a dinner party. Convinced he will want her back at his upcoming Labor Day party, she is determined to stay in the Hamptons for an extra week, a place where, “[t]he cars left unlocked, no one wanting to carry their keys on the beach. A system that existed only because everyone believed they were among people like themselves,” Cline writes.

Only Alex has nowhere to go. She’s banned from a slew of New York City hotels. Old friends and clients can’t get off the phone fast enough when she calls. Even another escort she runs into in a restaurant bathroom tells her to get lost. Meanwhile, she is hard at work pushing away the reality that a shadowy man named Dom is after her for a large, undisclosed sum of money and drugs she stole from him.

Despite a cultural obsession with the grifter that’s bubbled up in recent years, particularly around people like Anna Delvey, Caroline Calloway, and Billy McFarland, Cline started the book in 2016. She was inspired more by Tom Ripley than Delvey, as was she inspired by the setting of the Hamptons itself. Cline first visited Long Island in her mid-twenties. Coming from California, the setting felt “so alien and so controlled and so much about power,” she says, describing it as almost a microcosm of the same machinations of power in New York City. “I was just thinking about what a wild card character would look like in a place like that.”

Throughout the novel, we follow as Alex tries to traverse what feels like impossible levels in a claustrophobic video game, as she lives, quite literally, hand to mouth, and steadily terrorizes the town in the process: railing lines of cocaine with assistants, camping out in pool houses, charging cheeseburgers and beers to strangers’ beach club accounts, and pocketing sunglasses and cash. In place of a traditional plot structure is an addictive, sweaty immediacy: All she knows is where her next painkiller is coming from, though the bottle is dwindling fast.

Cline wanted each chapter to feel like its own short story, with a propulsive momentum that is more true to how life is lived, particularly if you’re wondering where you’re going to sleep or whether or not your ex-drug dealer is going to successfully track you down. “There's something about a short story form that's always felt a little more true to how life is experienced,” Cline says. “How I experience life at least.”

But while Alex is working so utterly hard at survival, she’s radioactive, not just to everyone around her, but to herself. She can’t help but take things too far: to skinny dip in someone’s pool as their maid comes home, flirt with someone’s husband, scratch a prized painting, steal a watch. The call is coming from inside the house, but the house is a Hamptons mansion.

“In many ways, she's her biggest antagonist and has this impulse towards self-sabotage. Even though at the same time, she's in some ways extremely controlled,” Cline says. “What is it in her that wants to scratch the painting or follow this impulse, even though it's going to make things worse? I wanted there to be this sense of: minute by minute there's this survival impulse. It's like, ‘Where am I going to sleep tonight? What am I going to eat? What am I going to do?’ But then also this existential hunger or void in her that's propelling her forward, and that is maybe not making the best decisions, but that kind of blind fumbling.”

We don’t know exactly what psychological underpinnings propel Alex’s self sabotage: The novel resists a lot of contemporary impulses, namely the insidious calculations of trauma math. We don’t know much about Alex’s backstory, no more than a lot of her boyfriends know. She was a sex worker until she started losing clients to “ultimatums eked out of couples therapy and this new fad of radical honesty, or the first flushes of guilt precipitated by the birth of children, or just plain boredom.” She drops her rates; she gets laser treatments marketed to those decades older than her. She can’t pay her rent; she meets Simon, “the emergency exit” at an upscale bar and tries to find a nice life, which works until it doesn’t.

“I think especially with a character who's doing things that a lot of people wouldn't do, there can be this temptation to want an explanation for why they are the way they are,” Cline says. “I feel like often it turns into this trauma math exercise where X and Y happened to them and now that you plug that in and it makes perfect sense why they're doing Y and Z. I really wanted to resist that kind of narrative about this character.”

Alex’s manipulations don’t have to be the result of some deep-rooted trauma; the fact that she is so socially astute tells us plenty about her. After all, people aren’t born particularly socially adept; usually, it’s a survival tactic. “With a character who is not going to have backstory or she's not going to be filled in that way,” Cline says, “I feel like it became more about, ‘All right, what is she noticing and can her noticing stand in for that character work?’”

But none of that means Alex is necessarily good at getting what she wants. In fact, she finds herself in a tailspin of increasingly inopportune experiences. But you can’t deny she’s an expert: She deduces cracks in emotional foundations with the flit of an eye or the shift of a posture. She knows when she should smile. Sometimes she falters: “She was off her game — her mind was blank, no answer floating up as it usually did. Alex made herself shrug.” It’s this prickly undercurrent that follows her as persistently as her painkiller high: the staunch, deluded belief that if she can make it to Labor Day, everything will be okay.

“She isn't someone who would dwell on her past or that she would have these almost willful blind spots about her own experience in psychology,” Cline says. “Even as she's somewhat very perceptive about people around her, there’s this also major blind spot about herself.”