Culture

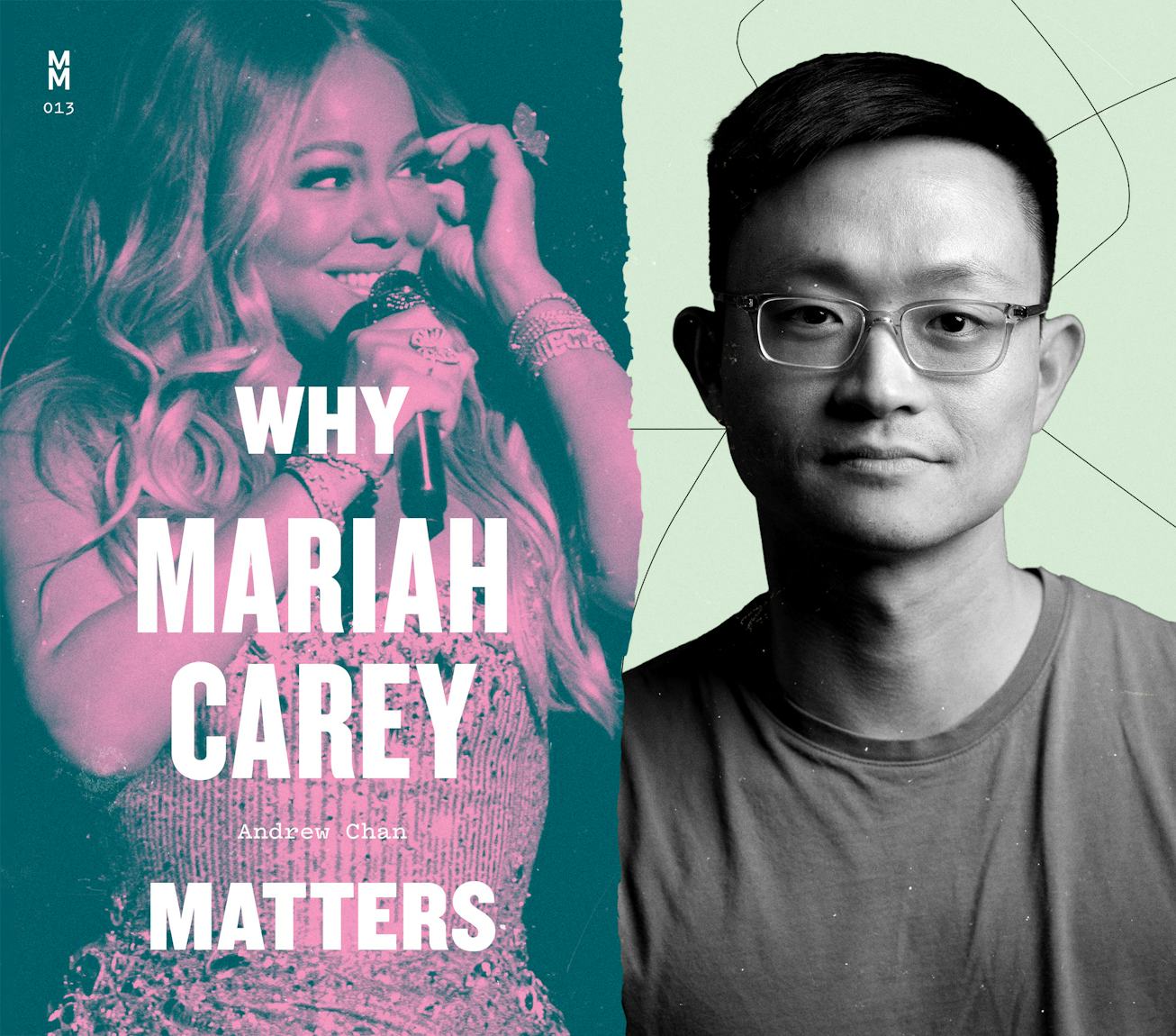

Why Mariah Matters Explores Mariah Carey’s Decade-Spanning Artistry

Editor and culture critic Andrew Chan explores the personal and musical depth of R&B and pop icon Mariah Carey in new book Why Mariah Matters.

Why Mariah Matters, the latest installment in the University of Texas Press’ “Music Matters” series, follows Carey’s 2020 memoir The Meaning of Mariah Carey, but the two share few similarities. Where Carey retold her life story in Meaning, editor and culture critic Chan pinpoints critical moments and milestones throughout the singer-songwriter’s 35-year musical journey, from her turn into house music on Music Box remixes, to briefly facing a career decline on 2002’s Charmbracelet. All the while, Chan shows empathy and grace for Carey, detailing the ostracism that she faced throughout her life, albeit being one of their greatest singers of all-time.

“Of all the major pop divas of [the ‘90s], she's the one who talks throughout her music about this feeling of being an outsider and how the pain of that will never completely leave you,” Chan tells NYLON. “There is joy, there is beauty, there is love to be experienced, but at the same time, the wound that was caused is not something that can just be patched up. I think there's something powerful about the fact that Mariah sometimes lets herself wallow, hurt, and experience abject grief, loss, and sadness, and she doesn't pretend there's some easy solution to that.”

Chan gives nuance in Carey’s work, persona, and legacy, also giving readers (and Lambs across the globe) the sensation of listening to the “Songbird Supreme.” Across 168 pages, Chan humanizes Carey’s world renowned impact in music, also connecting the artist’s poignant lyrics and five-octave singing delivery to his experiences as a queer Chinese-American. For Chan, whose family were early fans of Carey’s 1995 album Daydream, Carey’s voice defined the author coming into his own.

“When I was a child, it was the era when there was more queer representation happening in mainstream media. You knew queer people existed, but I grew up in a pretty religious household, in a pretty homophobic world, and that was the clarity with which she articulated the experience of being ostracized,” says Chan. “Putting myself back into the shoes of who I was as a child, hearing that was world changing for me. I can only imagine that other queer people who’ve experienced her music in childhood have very similar stories.”

NYLON spoke with Chan ahead of the book’s release to discuss Carey’s influence on Asian fans, Butterfly being her definitive LP, and the #JusticeForGlitter movement.

This book comes three years after Mariah’s memoir. What made you decide to write this narrative about her after she wrote a book about her life?

I definitely thought about what I could uniquely bring to the table since her memoir was so wonderful in detail and personally transparent. I wanted to make sure that a reader was going to get something that wasn't the same. But I also knew that it wasn't going to be, because I am a critic first and foremost – I am writing about my experience with the work of art.

I wasn't so interested in recounting the beats of her biography. There definitely are moments where I am contextualizing the music with descriptions of what's going on in her personal life, just so we know what she's drawing from emotionally and what the background is.

While celebrity is a fact in her life – she is a global superstar – it's not [important to] me. The most interesting thing about her to me, is the experience of one voice to one listener, her to me. One human being, conveying something deep from within her soul to this Asian gay child growing up in different parts of the world, and encountering her music. Then, what was important was to understand the culture, the cultural climate and the background of what was going on in music and culture at the time when she emerged and before she emerged that made her who she was. The writing of the book wasn't just an opportunity to share what I already knew and felt about her work, but also to try to understand how she [came] about.

Something that you often return to in the book is the range of her voice from her ‘90s power ballads to her whispery notes in the ‘00s. Can you recall the time where Mariah's voice began to resonate so strongly with you?

The first memory I have of making a mental note as a child of who she was, was this Thanksgiving concert special she gave in Schenectady, New York. It was timed to the release of Music Box, so I remember hearing her sing “Hero” and thinking, “Wow, what is going on?” I was already obsessed with singers, I grew up on Hong Kong pop and Chinese pop, because that was a lot of what my parents listened to, and there were these, definitive, quintessential, Chinese divas that I was obsessed with.

But I would say that my love for the music and for her voice really escalated with 1995’s Daydream which had “Fantasy,” “One Sweet Day,” and “Always Be My Baby,” — that was just a massive cultural moment. I was living in Malaysia at the time and those songs saturated the airwaves for two years. I heard it everywhere: on the way to school, on the way to swimming lessons. These songs and her voice would send chills down my spine as a kid.

In the book, you mentioned Daydream as the first Mariah Carey album that your parents purchased. You also write about her influence on Chinese and Filipino singing competitions. How would you describe the connection between Mariah's music and then the Asian diaspora?

Black American music, particularly R&B, has had a massive global influence. I just happen to be more attuned to its effect in the global Asian diaspora, because I am Asian. But the Philippines, for instance, is known throughout Asia as a country that has a very high proportion of virtuosic singers. I'm not just talking about good singers, I'm talking about the singers who can sing their face off.

This particular style of singing that was popularized and globalized by Mariah, by Whitney, by Celine, has had a massive impression on generations of Filipino singers. For the book, I had the chance to talk to Regine Velasquez, who is probably the greatest belting diva of the contemporary Philippines. She had a big voice, a massive range, and it was really hearing Mariah that enabled her to find a niche in the market, because that's what became popular.

Mariah was so palatable to such a broad audience, because partly, that was how she was marketed in her early years by her [former] record label Sony. But because she showed such devotion to R&B and hip-hop, particularly starting in the mid-90s, she was part of the reason how those two forms of Black American music became so global. Down the line, a lot of the great and popular Filipino singers are emulating Mariah, and you hear R&B and hip-hop influences in K-Pop. Taiwan has belting divas of their own, Korea does, too.

Early on in the book, you mentioned that Mariah's sophomore album [Emotions] earned her a Grammy nomination as a producer. She's talked about being a musical perfectionist, but what was the importance of emphasizing her work behind the boards?

It is wild to me that people don't talk about that more; you hear the perfectionism in the records. One of the things that makes Mariah so special within the pop diva category is the fact that she is as much of a producer and a vocal arranger as she is a lead vocalist. She talks about loving background vocals perhaps even more than she does recording the lead vocals.

There was this interview that she did recently with Rolling Stone where she said that [when] recording the Butterfly album, she often started with the background vocals, which was kind of mind blowing to me. You think of background vocals as the garnish or embellishments or there to add some flavor; it's not necessarily supposed to be the main course. But this is part of her artistry, the background vocals and these densely layered soundscapes that she creates with her voice, usually all her own voice, just stacked dozens of times, is a crucial part of understanding how her artistry is unique within the landscape of ‘90s women’s singing.

People were using background vocals for decades, but she uses them in a very intricate way. You almost get lost in the waves of sound that are coming through your headphones. You hear the perfectionism also in how deft she is as a songwriter in finding earworm bits of melody and harmony. In her most perfect songs, like “Always Be My Baby,” every section of that song is unforgettable and it works together, cohesively. That's her brilliance as a pop songwriter; she knows what's delicious to the ear and she can do it in a wide range of styles.

Butterfly marked a turning point in Mariah's life as she separated from Tommy Mottola and her sound became a little bit more hip-hop. You said this was a definitive album for her. Why do you consider it to be that way?

It wasn't that Mariah had never done R&B and hip-hop before. On her first album she has a song called “Prisoner” where she’s rapping. This kind of idea that she was this mainstream, kind of white-coded pop artist is more complicated than it seems, because she was always giving R&B, even if she was marketed as pop.

But Butterfly is a major sonic change. At the very top of the record, you have a Bad Boy production, you have Puff Daddy and Q-Tip collaborating on “Honey.” Later in the album, you get a Mobb deep sample on “The Roof,” then by the middle of the album, you're getting Bone Thugs-N-Harmony with “Breakdown.” It's really putting hip-hop forward where on previous records, it was the remixes that were doing that work of giving something to the hip-hop audience. You can hear Mariah's love for this music in the way she delivers it.

It's a shame that more people don't know “Breakdown” because to me, it's a monumental, artistic breakthrough in R&B and hip-hop music. It's not just someone singing over a hip-hop beat, it is one of the greatest singers in the world singing in a rap cadence of some of the most virtuosic emcees of that period and making it hers. I don't want the Lambs to come for me, but I want to say that that is a more monumental hip hop-breakthrough than the ODB “Fantasy” remix. It’s fantastic, but it's basically the old the album vocal reused but ODB’s verse, whereas “Breakdown,” you're hearing her go toe-to-toe with Krayzie Bone and Wish Bone, and making it make total emotional sense within the context of what the song is talking about, which is the breakup of a relationship.

I think it's an absolutely brilliant album. I think it makes sense that at this moment of emotional crisis in her life when she's separated from Tommy Mottola, and is seeking liberation through music, that she would produce some of her most revelatory work in this period. It's a sonic reinvention for her. I think Butterfly is an artistic breakthrough for many reasons, partly the integration of hip-hop, partly the integration of a softer, more nuanced and subtle vocal approach, and also the introspection that you hear in songs like “Outside” and “Close My Eyes.”

Let's talk about Glitter, her semi-autobiographical film that was released in 2001. The movie had its own #JusticeforGlitter moment in 2018. How are you able to perceive Glitter with fondness despite it having such critical panning when it came out?

I'm a huge Mariah fan but it's taken me years to get around to watching it, just because I think I had internalized some of the dismissal. I come from a film background too, so I was very aware of the fact that this was supposed to be a bad movie. In watching it more closely for writing the book, I found it to be a very interesting movie. I don't think anyone would claim that it's an artistically successful movie, but I think it gives us how Mariah wanted to be perceived [as] one of the great pop stars of her time. Also, what it shows us about the evolution of R&B in the ‘80s is really interesting; you can't find that in any other movie, really.

At this point in her life, Mariah was starting to show people that she had struggled in her childhood and that she came from a difficult background. This was something that she didn't really talk that much about in her early years when she was married to Tommy Mottola. It was kind of a squeaky image that was cultivated for her, or I'm sure she had a part in cultivating it, too. In placing herself within this narrative of trials and tribulations both as a child and within the music industry by the time the protagonist, Billie, grows up, you can see that she is trying to help us understand where she's coming from as an artist. She did not grow up with a silver spoon in her mouth. She had hard times, and importantly, she is a woman of mixed-race identity.

It is not a great film by any means as an artistic achievement, but it is interesting in terms of what it reveals about her and about the backdrop of R&B music at the time. #JusticeforGlitter made sense to me because Glitter is a fantastic album. She's working with Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, whose music she idolized when she was a kid. That ‘80s sound that she grew up on, it's incredibly nostalgic and it contains some of her best singing, from the ballads like “Lead the Way” to more uptempo stuff, where she’s doing her own version of post-disco. We can stop looking at it as an embarrassing moment in her career and see it as she was playing with a retro ‘80s sound.

Another era that you were critical of was her Rainbow era, because that was the period where she was attempting to fit into the bubblegum pop mold. If it weren't Rainbow, what would you have wanted to hear from Mariah in 1999?

I worried about that part because Rainbow is beloved by a lot of Lambs and it has wonderful moments. Visually, Rainbow is so queer-coded; it’s called Rainbow, the cover photo was done by David LaChapelle, who aesthetically has a very gay campy style. But for me, it is the album with the most skips. Still, to this day, no matter how much I listen to it, it sounds a little thrown together. I learned in the memoir that she recorded it in three months in a desperate attempt to get out of her recording contract at Sony Music, after the divorce from Tommy Mottola.

But I appreciate that she was digging into different sides of hip-hop, because she has Master P and Mystikal on one of the deeper cuts. It’s great to hear their gruff New Orleans sound against her really pretty vocals. But what I would have loved to hear would have been more introspection. That does happen on a song called “Petals,” which is one of her darkest songs, but I would have loved to hear more in that vein, something more personal and soulful from her.

Why Mariah Matters is honest about her personal struggles. Why do you think Mariah has persisted despite the ups and downs of her career?

I think music is a salvation for her. Even though she's not as not turning music out the way she was in the ‘90s, she still seems artistically hungry when she does put out music. I think of [Me. I Am Mariah…] The Elusive Chanteuse, the music on there is so searching, seeking, emotionally open – she still has what it takes to be an artist using her craft and her genius to make sense of her world.

There are many reasons why an artist can be great, it just so happens that what makes Mariah stand out is this idea of salvation. It's a little spiritual, it sounds a little mystical but her music, people talk about how it has saved their life. I think she takes that very seriously because she has spoken about how music saved her life.

How did documenting Mariah’s journey help you contextualize your own?

When you have loved an artist as long as I have loved Mariah, you can pinpoint memories and moments of your life to specific albums, specific songs, specific eras of her career. You know her persona so well that you can almost feel where she's at in her life through the music. These kinds of long-term pop star careers, the way we engage with them, we’re marking time in our own lives. The familiarity of her voice, the familiarity of those melodies, it's almost like solid ground on which to stand sometimes through the twists and turns of my own life. Her life is a story of resilience and she offers us fans an example of how to carry on.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.