Entertainment

How Rob Zombie's Films Perfectly Depict The Lingering Horror Of Female Trauma

They listen, even as they scream

I told a yoga teacher friend of mine I was writing about the way female trauma is framed in Rob Zombie's movies, and her face dropped. She told me she'd been to one of his concerts and felt borderline unsafe, the imagery and lyrics seemed misogynist, and the fans moshing along to what she saw as a threatening message made her sick. I said that seeing the wrong few of his movies might not initially cure her of the idea that Zombie's movies are not a safe space to be a woman. Women, after all, are murdered, assaulted, beaten, screamed at, made the eyewall of a storm of pain. Zombie's art undeniably takes female suffering as its subject, but the sensitivity and pointed truth of his images doesn't emerge unless you gird yourself against the shock and ruin, the coarseness of his vision of violence. Once you've immersed yourself in his worldview, it becomes a place almost calming in its cankerous abjectness.

In order for the chaos to work, there must be a base level of calm, and Zombie's become an expert at juxtaposing his unique version of the two. Who else but he would pause his newest film, the Sam Peckinpah and Jim Thompson influenced neo-Western 3 From Hell, to show you a psychotic woman's hallucination of a kitten visiting her in her prison cell. You have to be willing to endure the unendurable to see what Zombie has doggedly provided for his viewers over nearly two decades as a fiction filmmaker: the reality of survival and a gentle reassurance that whatever you're feeling afterward is legitimate and correct. Each of us suffers in some way, and he wanted to pay tribute to the kaleidoscopic forms of pain and coping take by showing the myriad ways we die and survive. His films listen even as they scream.

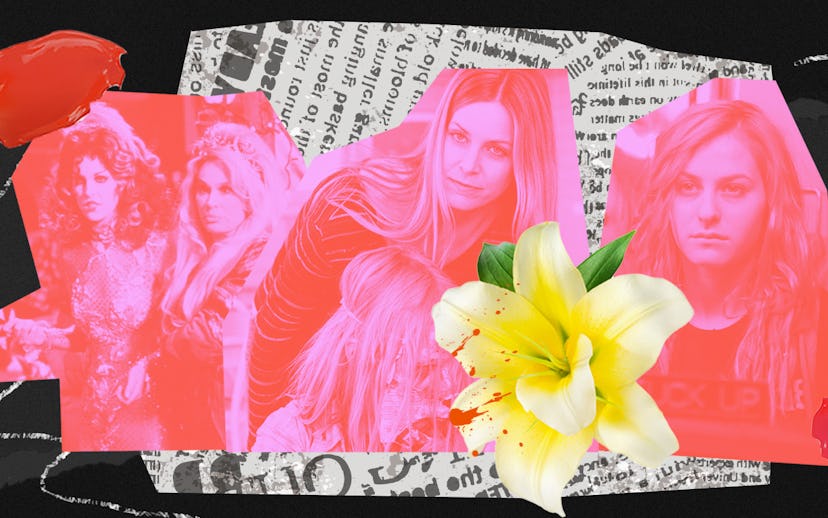

Zombie's first film is the larger-than-life provocation House of 1000 Corpses (2003), and there are only a few hints about the artist who'd emerge from behind the music video editing, the caffeinated tangents, the baroquely profane language, and the seeming senselessness of the action. The film, set in 1969, follows a group of amateur reporters obsessed by true crime who luck into a local legend looking to be exploited. A curio shop/wax museum owner and part-time clown named Captain Spaulding (Sid Haig) tells them there's a murderer named Dr. Satan whom the natives whisper about, and if they want he can point them in the direction of his old stomping grounds. The men on this mission (Chris Hardwick and Rainn Wilson) while away the trip with talk about the relative good looks of the then-just arrested Manson girls, evil and carnage abstract to them until they come face to face with it. Their girlfriends (Jennifer Jostyn and Erin Daniels) are clearly just humoring the boys and are the first to see the many red flags springing up as they fall into a trap sprung by Dr. Satan's still-living cohorts Baby (Sheri Moon Zombie, the director's wife and muse, and one of the most versatile performers in the American cinema), Mama (Karen Black), and Otis Firefly (Bill Moseley). Zombie here introduces the idea that whatever acts of terrorism the men in his movies commit, the women have to live with everything. When Wilson and Hardwick are killed by Otis and his family, it's Daniels' Denise who has to see it happen, has to survive the night, has to live with the memory and still keep her wits about her.

The Halloween movies are where the pathology of suffering is set in stone in Zombie's methodology as writer and director. The first of his Halloween movies (2007) is about Michael Myers (Tyler Mane) slowly abandoning his concept of empathy and becoming a hulking killer, driven only by his desire to reclaim a lost childhood. His mission purposely has no nuance, even despite a lengthy origin story. He remains a murderous cypher, killing real, detailed people. Even characters with mere minutes of screen time are shaded better than Myers. None of Zombie's killers are meant to be pitied, it would defeat his purpose. The victims and the way they process what is happening to them is the most striking and oft-repeated feature of Zombie's work. The Halloween movies are transfixed by the sound of people shrieking and pleading with a man who very suddenly represents the cruelty of an orderless universe. We're allowed windows into each of his victims' lives, most of them women with desires and flaws. The Halloween movies only work as tragedy because we know the promise these people hold.

The first person truly destroyed by Michael Myers aren't the family members he kills but the mother he lets live. Deborah Myers (also played by Sheri Moon Zombie) loses her daughter and boyfriend, and then her son when he's locked up and refuses the help offered him by psychologist Dr. Loomis (Malcolm McDowell). She puts all her hopes into helping coax some form of an explanation from her son as to why he snapped and in so doing the will to live drains out of her. Michael gets hours of treatment from a gentle doctor who cares about him and hugs him, and encouragement from the lonely janitor (Danny Trejo). Deborah Myers gets nothing but constant reminders that she "failed as a mother and lost her family, a narrative thread that takes up a shocking amount of time in what was marketed as a gory remake of a slasher movie. She'll kill herself while watching home movies of her once happy family, unable to carry on while her sociopath offspring grows more cold and indecipherable. The absence of his mother's presence is what renders him mute and inhuman, where before he was simply unresponsive to love and attention. Without her, he's pure masculine rage, forcing women to take part in a ghastly reenactment of his violent childhood; a canny understanding of the male ego. Teens Laurie Strode (Scout Taylor-Compton), Annie Brackett (Danielle Harris), and Lynda (Kristina Klebe) are stalked and tormented while with their expendable boyfriends, while Laurie's mom (Dee Wallace) has to see her husband die and then watch helplessly as Myers leaves to go try and kill her daughter. They're forced to bear witness to cruelty, more damaging than simply being attacked with a knife in Zombie's world, because the experience will change your worldview if you somehow manage to survive the trauma within and without.

Halloween II (2009) is about precisely that shift in consciousness and the agonizing business of living with guilt and grief. The film starts with a dream of Laurie escaping Myers after the end of the first movie. Zombie's camera surveys the bestiary of wounds Laurie suffers, the close-up surgery, ripped fingernails removed, stitches on her face—the real toll of horror movie violence. In lingering on the weeping cuts and convulsing figures after the attack, he's taking responsibility for and subverting the expected content of horror cinema. People don't stop bleeding just because the credits roll.

In her nightmare, Laurie has to run away from Myers when he comes to finish her off, but can't because of the cast on her foot, the pins in her arm, and the disorienting head trauma; he's turned the symbolic anguish with which she'll spend the movie into literal stumbling blocks to show how difficult it becomes to do something simple. Laurie can't walk down a flight of stairs with her injuries, and she can't get through the day without PTSD-induced panic attacks. She will not allow herself to believe that what happened to her and fellow survivor Annie wasn't her fault. Laurie wakes from the nightmare coated in telltale signs of lost purpose. Her room in Annie's house, where she now lives, is coated in spray paint and band posters, her hair has gone months without maintenance, and she has a tattoo on her lower back. These signifiers paint a portrait of a much different Laurie Strode than the responsible babysitter attacked in the first movie. Everything around Laurie is different, and the large but cramped, agreeably unclean Brackett house is a mirror of her mental state. She can't seem to escape feeling that she deserves her scars and caused Annie's, a bold fixation for a movie that could have just been about more random acts of violence against teens.

Halloween II features lengthy scenes of Laurie trying and failing to cope with her grief. She has nightmares from which she wakes screaming, she can't get through meals without throwing up, she takes her aggression out on Annie whose scarred face is a "constant reminder. Every time I see her face and those scars, I know it's my fault." She goes to a therapist (Margot Kidder, who knew a thing or two about feeling alienated) and has to remind Laurie that her violent feelings, which Laurie associates with her attacker and assumes will lead to her commitment, should be explored rather than ignored. "We're here to keep you out of a hospital," is the doctor's attempt to calm Laurie down. The onset of Halloween decorations all over town will later send her into a hysterical crying jag, and she'll demand more medication to deal with her runaway emotions: "I'm not strong enough, and I'm tired of pretending that I am."

Halloween II is a film about knowing you're being compelled to destroy yourself and not being able to stop. Laurie turns down help at every turn, lashing out at Annie and her therapist, because her brain wants her to live in the space of helplessness her pain provides. It's easier to act out and ignore the way to a healthy co-existence with a churning morass of grief, blame, and fear. "What am I gonna do?" Laurie asks aloud to no one in particular, precisely the kind of over-inflation of personal responsibility endemic to grieving losses we didn't cause. Laurie wants to live life with the same intensity her demons gnaw at her peace of mind.

Zombie's movies have never been popular or well-liked. They have have been hacked apart by critics and to put the box office into perspective, the 80 million dollars that Halloween took is 75 percent higher than the average gross of the rest of his six movies. The reason could be the public's turn against the kind of violence that has become a trademark of his cinema, but it's always seemed equally likely that the emotional openness has seemed unattractive to some people. If the Zombie brand, so to speak, were strong enough, surely something like Lords of Salem would have earned more than just its meager budget back. It wasn't so much a departure as just a longer drive on a road down which Halloween II had veered. The autumnal setting returned, as did the openness about depression and the lengths we go to find relief from our symptoms. Sheri Moon Zombie plays Heidi, a DJ with a whole life of partying and substance abuse written in her dreadlocks, chosen by a coven of local witches to be the vessel for their new messiah. The witches see someone with few friends, no confidence, no family, and a host of exploitable weaknesses. She goes to Narcotics Anonymous meetings, drinks heavily on and off the job, and feels professional and social pressure from her co-workers (Ken Foree and Jeff Daniel Phillips) to keep her easy-going party girl image alive. The witches in her apartment building barely need to lift a finger to twist Heidi's vices against her. Soon after they set their sights on her, she stops reaching out to friends, stops attending meetings, starts seeing visions that could be satanic or simply the product of insomnia and dependency, and in a heartbreaking final act plummet starts using again.

Zombie has quietly turned horror's dramatic conventions into mirror images of the way people fend for themselves mentally. Heidi's descent back into addiction and feeling worthless deliberately echoes the way she's groomed by the devil's disciples for a Rosemary's Baby-style impregnation. Laurie Strode spends an entire movie recovering from the wounds suffered in a routine slasher movie attack, complete with therapy, substance abuse, and chasing away loved ones. When she's targeted once again by her attacker, she behaves more like someone who's run into her abuser than like the heroine of a teen horror movie realizing the killer has come back for more. Her complexes are subject to calcination when Michael Myers reappears and she imagines herself literally held down and bound by visions of his id. The idea of violence becomes intrinsic to the idea of losing one's stability.

In Zombie's 2016 crowd-funded film 31, a group of carnies are hunted and killed for sport, and while they use chainsaws and knives to do their killing, it's the threat of sexual violence that lingers longest. The language of the attackers leans heavily on sexual assault. Venus (Meg Foster), one of the carnies, will have a nightmare, the only full glimpse into any one character's unconscious, where she's held down and subjected to jokes about rape. When Charly (Moon Zombie once again) is caught by Richard Brake's Doom-head, sent expressly to finish her off, he blows his chance at killing her by enjoying the experience of having power over her too much. He knocks her down and strangles her, but can't help first but mansplain his interests for a few minutes too many, running out the clock on the game of death. It's the humorlessness of men that stalks Zombie's heroines and very few male directors understand the potential for misery that men represent, from murder to quoting Che Guevara.

Zombie's heroines come in many forms, but they all find themselves down the barrel of male egos and the violent instruments they use to express themselves. In Rob Zombie movies, men tend to show their emotional inner lives through violence, sexual posturing, profanity, and terror (there are exceptions, largely found in Lords of Salem). Women have to endure it, their inner lives a threat and affront to the men who hate them. Their challenge is to retain that same humanity that made men like Michael Myers want to kill them. The reality is they can't, not fully, and Zombie's kept his camera rolling to show you what it looks like when someone looked at you and saw a victim, but you beat them. The final image of 31 finds a bloodied and exhausted Sheri Moon-Zombie staring down Brake, her would-be murderer, clenching a fist and deciding she won't be letting this man be the end of her story. She has everything taken from her but doesn't give in spiritually, though, as he highlights in Lords of Salem and Halloween II, not everyone has that luxury. Sometimes the world is too much and surrendering or being bested by it is not cause for scorn, but for sympathy. Strode winds up institutionalized at the end of Halloween II completing the cycle of pain that began when Myers broke out of a facility to come reunite them as family. Heidi vanishes in Lords of Salem, subsumed by darkness and her own doubts that she deserves a second chance. There isn't always a happy ending in tales of illness and our own darkness. It's not a hopeful prognosis, but a realistic, gratifying one. Sometimes not being understood is as scary an idea as being killed.

The flip side of all this can be found in the cathartic bathos of Baby Firefly, the one female character whose agency comes not from being plagued but rather because she herself is a plague. Baby is alone among Zombie's villains in that she isn't afraid of showing her face, of taking full responsibility for everything she's done, unarmed, in jail, defenseless and tied up. She's the only one who's fearless before her own mortality and the true staggering hideousness of her crimes. She's the mirror image of the female victims in his movies, forced into nakedness, sometimes real, sometimes metaphorical, before the violence of depraved men. In House of 1000 Corpses, The Devil's Rejects, and 3 From Hell, Baby taunts people with childish abandon, knowing her inability to seem affected by what she's done or been through is not just unsettling but downright enervating. It's the lack of empathy that bothers the other characters, the seeming unresponsiveness to their version of her depravity. Several crazed law enforcement officials think they can best her through the kind of violence she commits, but her unemotional response keeps her a step ahead of them. Zombie doesn't ever hand us a Rosetta Stone for Baby's state of mind, offering only her crimes, and her inability to consider them once they're done. She remains defined by a core absence of feeling for the people she harms, though we know she's capable of affection for her family, which makes her disdain for the rest of humanity all the more chillingly random. Zombie offers her the world free of consequence, able to maim and murder whomever she pleases. She's the negative image of Zombie's female victims, the woman who has no need for vengeance because she kills everyone first, the woman in Zombie's world who exerts control over a lawless universe. This necessarily involves horrible criminal acts, as Zombie's set those as the outer reaches of the experiences of his characters, and Baby enjoying them is just as complicated for viewers as watching Heidi or Laurie suffer. Baby's actions are without morality, which makes her enviable in as much as she isn't beholden to the systems that govern the rest of the world. Watching her get away with murder can be gratifying when she kills bad people, and it can be chilling when she does the same to innocents, the trick is Zombie never chooses for us.

Horror movies by their nature have to involve suffering, but few of them take the time to live in the moments of degradation with such patience, or indeed to stand over the wreckage and watch someone try to crawl away. When Venus, Mama Firefly, Annie Bracket, Mrs. Strode, and the female victims in Halloween II are stabbed, it's not easy, it's not fun, it's not meant to be. It hurts. It has the awful intimacy of sexual assault (also a feature of these movies), of men exerting too much power over women. These moments have to be the worst killings in screen history or the fallout from them, the catatonia and convulsions, the bottomless terror won't mean what it does. Watching someone shriek from the depths of their being is a way for us to identify with the parts of ourselves we frequently have to hide to get through our days. It's socially unacceptable to scream out our pain whenever we feel it, to do something to relieve ourselves of the burden of our neuroses and trauma, no matter how universal.

Zombie gives us reason to share our trauma with his images of the same, supercharged generic iconography meant to force us into a place of discomfort through lingering on the unthinkable. When Laurie Strode screams, she does so for those of us who can't.