Fashion

Sexism Sells: An Evolution of Selling Sex In Advertising

In 2020, there are subtler ways sexism has snuck its way into TV spots and print campaigns

Just last year, OnePoll and Pure Romance surveyed 2,000 Americans and found that people think about sex (the act) eight times a day, while managing to drop it into conversation at least five times a day. By the numbers, the presence of sex in advertising has two legs to stand on. However, as female pleasure — or anything outside of cis male pleasure — has barely been accepted as non-taboo (take the vibrator company Dame Products suing New York's MTA for refusal to run their ads while erectile dysfunction company Hims plastered images of little cacti throughout the subways, for example), the concept of "sex sells" has a history wrought with sexism.

Though memorable examples from Herbal Essences, Calvin Klein (portraying a 15-year-old Brooke Shields very sexily) or Wonderbra's "Hello Boys" ads featuring Eva Herzigova in their push-up bra may point to the 1980s and 1990s as extremely sexist times in advertising, it's believed that the first appearance of "sex sells" was in 1871's ad for Pearl Tobacco. Yes, a genderless product was the first to introduce sexism into hawking goods.

Surely, with these examples being 30 to 40 years in the past, one would think there's been some change, and they'd be right. There has been some change. While we've progressed from the outright inferiority of women — like Drummond's Sweaters' 1959 ads that claim "men are better than women!" in the copy — there are subtler ways sexism has snuck its way all the way through to today.

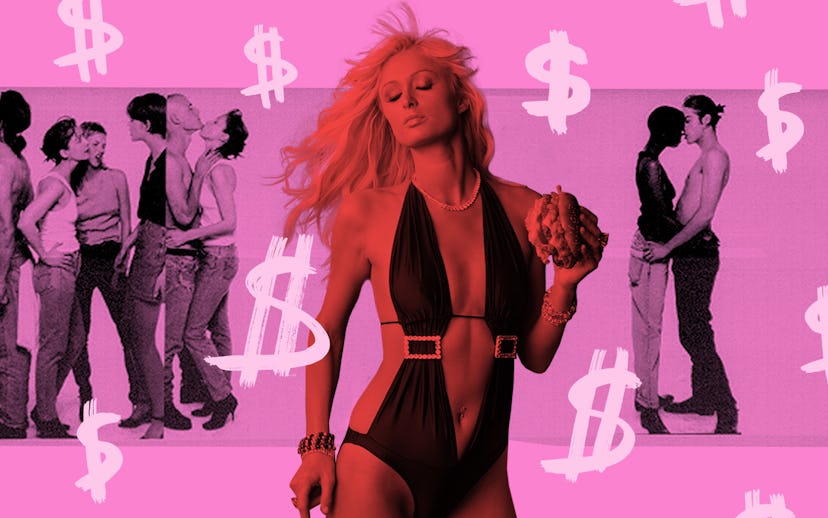

In 2005, burger chain Carl's Jr. put together a 60-second television spot featuring hotel heiress, reality TV pioneer, pop singer-turned-DJ, and turn-of-the-century "bad girl" Paris Hilton provocatively washing a Bentley. The ad received a good amount of criticism for exposing young people to sexuality (and less feedback about misogyny) but ultimately continued to run. Carl's Jr. even made a site specifically to view the ad at SpicyParis.com, which drove significant traffic.

First, this ad was effectively selling sex and money (and what might read as power) rather than burgers, but as Hilton bounced back from a sex tape scandal, it could be argued that while men want her, women want to be her or have her lifestyle. However, portraying her under the guise of "women want to be her" is sexist in itself, because it indicates that women also want to cater directly to the male gaze via wet bodies, cars, and juicy burgers. This was considered so successful that Carl's Jr. doubled down and offered a rebooted version of the commercial nine years later in 2014, with Hilton alongside swimsuit model Hannah Ferguson.

As recently as 2015, Gap — the all-American brand that probably wouldn't fall into the category of using sex to sell clothes — received criticisms about a Gap Kids ad. In a U.K. campaign, the U.S.-based brand called boys "little scholars" and girls "social butterflies," upholding biased gender roles. Although it's sending a sexist message to children that boys are smart and girls are, well, social, Gap Kids wasn't even close to the worst case of misogyny we've recently seen.

Undertones of forced sex and violence towards women was deemed marketable by Dolce & Gabbana when they released a campaign that drew comparisons to gang rape in 2015. Three years prior, Belvedere experienced backlash from an ad depicting a woman that appears to be desperately trying to escape a man that read, "Goes down smoothly every time." It's frightening to consider how many people approved comparing vodka to women who didn't want to be raped, especially within the past decade.

Finally, after 20 years of building a brand on toxic masculinity-centered stereotypes, Unilever's Axe flipped from body spray so good it inspires beautiful women to give men wearing it a blowjob to empowering men to "find their magic" — or be true to themselves regardless of where their masculinity falls on the spectrum. It's easy to assume that advertisements centered on the superiority of men over women are being made in rooms full of men (or rooms of men and women where the men believe women are inferior to men), resulting in output like the Gap Kids ad.

"I did a project maybe two years ago where the client said, 'We've done some research that shows when we portray people in general — not just women — in non stereotypical ways the ads perform better,'" freelance creative strategist Heather LaFevre recalls, in disbelief that it took research to tell them this.

A 2014 study of creative directors by the 3 Percent Movement found that women held 3.6 percent of creative director roles, 9.6 percent of art director roles, and 11.6 percent of copywriting roles. We can look at Mattel's gender neutral doll or period underwear THINX's inclusion of a transgender man in their campaign as progress, but it's clear that despite brands creating output that appears to prioritize equality, it isn't necessarily being put into practice in the office.

"It starts to be this echo chamber of 'somebody starts being more progressive and then we've got to be progressive,' but it's almost a cover-your-ass methodology of doing it," LaFevre laments. Admittedly, she's starting to pivot her career away from agency gigs. "I'm tired of being the only woman. I don't feel heard and I can't do it anymore."

The more things internally stay the same, the slower they come to pass. However, despite the gender pay gap still sitting around 79 cents to the dollar (and progressively worse for Black, Latinx, Native American, and Pacific Islander women), it's known that women's buying power has increased from $29 to $40 trillion from 2013 to 2018 with women driving 70 to 80 percent of buying decisions.

Millennials also spend money differently, valuing experiences and being both aware and invested in brands' ethics. "Millennials eat brands like Pac-Man and you really have to make sure that you're telling an interesting story that connects to your products," LaFevre says.

Additionally, as Tarana Burke's #MeToo movement developed over the last decade and exploded in 2017 with countless accusations of abuse of men in power, society's acceptance of sexism and sexual abuse is continually being worn down. In the U.K. in 2019, laws were put into place to disallow marketing communications that "include gender stereotypes that are likely to cause harm, or serious or widespread offense." Countries like Norway, Spain, and Australia have had laws like these for some time, while the U.S. only regulates ads targeting children.

Although we've come to see ads like Nike's "Dream Crazier" — the brand's most viewed video content ever, narrated by Serena Williams and featuring the U.S. Women's Soccer Championship Team — and beauty brands featuring men, it's evident that sex will always sell and sexism will continue to sell to those that are sexist. Until the buying power is greatest among those for gender equality, or brands recognize the value in removing gender stereotypes from their marketing, it's likely we'll continue to see old rhetorics slip between the cracks.