Entertainment

Netflix's Ted Bundy Docuseries Makes You Uncomfortably Intimate With The Serial Killer

We spoke to the director of 'Confessions of a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes'

On the 30th anniversary of Ted Bundy's death by execution, Netflix released a four-part docuseries about the life and crimes of the infamous serial killer. In it, we're let into the mind of the killer for what feels like the first time, and are closely confronted with his thought process. It's terrifying, to say the least. His is a story many of us have heard before, to some extent, but this telling is unique: Stringing each part together are audio snippets of Bundy himself, narrating his story the way he would have wanted it to be heard. This can seem fraught, like we are giving the murderer a kind of agency and power he doesn't deserve, but what soon becomes clear is that Bundy is not in control the narrative; quite the opposite, in fact.

Says Joe Berlinger, the director and executive producer of the series, Bundy's story is "kind of the Big Bang of true crime," and that our current "insatiable appetite" for the genre can be traced back to Bundy's 1979 murder trial. According to Berlinger, his trial shaped the coverage of criminal trials in the news, and our hunger to watch. "It happened at a time when the technology for covering news was changing," he said. "There came an explosion of cable stations and the 24-hour news cycle." In 1980, Bundy allowed journalist Hugh Aynesworth to interview him and record the conversations to use for a book, which are used to tell the story in this series.

Berlinger made the choice to use these tapes to guide the narrative of his docuseries, but "contextualizes them through interviews with a Greek chorus of people who had interactions with him in one way or another. There's no one in the show who's just talking as some expert who had no experience with Bundy." And, obviously, these firsthand accounts completely disprove the stories that Bundy wanted to tell for himself. One such story that Bundy tries to tell was that he had a troubled adolescence, which he then implicitly blames for his actions, without actually confessing to his crimes. Not fitting in with his peers and constantly being rejected by girls are among Bundy's infuriating excuses for his later violent acts. Berlinger doesn't care for this noxious excuse, which is told time and time again by men who have killed women. "I have a hard time ascribing to these kinds of reasons," Berlinger says. "Those may have been precipitating events, but, if you're a homicidal maniac, if it's not those precipitating events, then it would be other precipitating events."

Berlinger also recalls Bundy's trials, in which Bundy acted as one of his own defense attorneys. "Likewise, he allowed authors to access him for a book, which is why the tapes were made, and, in his mind, he had still not admitted to his crimes," Berlinger says. "When he agreed to allow these authors in, he thought he was looking for them to re-investigate his crimes and to prove him innocent. But, just like in the trial, his narcissism made him do things like re-visit the crime scene in the same way." Bundy was asked by journalists to speak about his crimes through the eyes of a third-person expert eyewitness, but when he did this, it became obvious that "all of his third-person commentary could only have come from somebody who knew details that nobody else knew." In other words, someone who was there—the murderer. Though Bundy was able to understand human thought processes and social interaction on a base level—he even went studied psychology in college—he was surprisingly incompetent when it came to handling his own story. When allowed to speak for himself, he reveals the things he didn't want anyone to know, and basically confesses his own guilt.

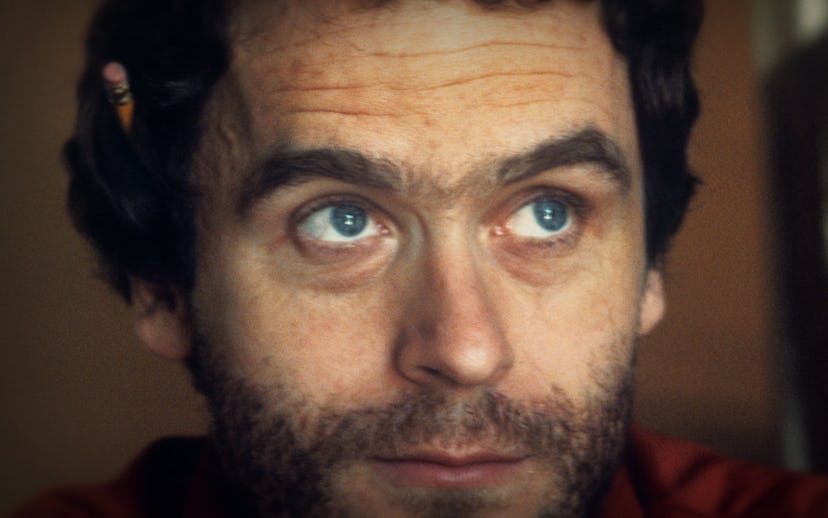

Something said to make Bundy's story so different from any other serial killer's was that he didn't look or act like what people imagine a serial killer should look and act like. "He defied the stereotype of what a serial killer is," says Berlinger. "He was likable, he had friends, he had a live-in girlfriend. He could have been a lawyer, he could have had a career in politics... There's no reason that he would do these things." This docuseries really captures that, in the most unsettling way—and what's more, it often actually comes from his own mouth. Berlinger explains: "As Bundy said himself, 'Killers don't come out of the shadows with long fangs and blood dripping from their chins.' They could be people you work with, love, admire, who then, the next day, could turn out to be the most demonic people imaginable." Bundy was certainly selectively self-aware.

What Berlinger really wanted to get across was that serial killers aren't in any way special—Bundy certainly wasn't. "It's the first time you can understand what has been said intellectually [about his case]," Berlinger says. "When you listen to these tapes, you get a sense of his normalcy—which is scary—and you get a sense of his charm, which [allows you to] understand how he was able to coax so many unsuspecting women to their deaths." Bundy's story is in opposition to our understanding of serial killers, and it forces us to confront our stereotype of them as "somebody who's a real social outcast, a real oddball that you could spot a mile away." We cling to those perceptions as a way to feel safer, but, with this series, as we "enter the mind of the killer," we realize more than ever how that sense of safety is an illusion. Still, though, I couldn't look away.

Conversations With A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes is now streaming on Netflix.